With Alaska and adjacent seas increasingly attracting everybody's attention because of their vast resources, many wonder how Washington will combine their development with preserving Alaska's unique social and ecological system – two priorities that have little in common.

Much like any other polar country, the United States views the Arctic as a geopolitical and geo-economic priority, largely due to its colossal natural riches, some of which are already being extensively exploited.

The only Arctic state, Alaska is the second largest producer of gold (after Nevada) and provides 8 percent of the national silver output. The Red Dog mine in northern Alaska boasts the world’s largest zinc reserves, producing 5 percent of the global output and 79 percent of the total U.S. output. That mine also produces 3 percent of global and 33 percent of American lead.

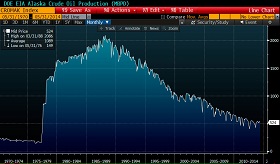

Alaska is also America's second largest oil producer, at 20 percent of the total extracted volume. And more huge oil and gas-bearing formations have been discovered in northern areas. Prudhoe Bay is the largest traditional continental field, which accounts for 8 percent of the national oil output. Oil revenues are especially important for the state, as they constitute 98 percent of resource-based budget revenue [1] and 90 percent of total revenue. [2] Fifty percent of the state's employees have jobs related to oil production and transportation. [3]

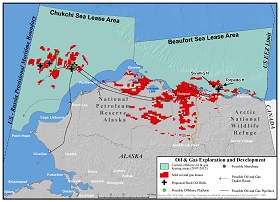

The northeastern part of the state comprises vast lands occupied by the National Petroleum Reserve of Alaska (NPRA), where known oil reserves are kept untapped for strategic and ecological reasons and only limited geological surveys are allowed.

Both Washington and Alaska have their eyes on hydrocarbon reserves in the Arctic shelf. The North American share of unexplored oil reserves is estimated at 65 percent and 26 percent of the total gas reserves. The bulk of this oil lies off Alaska.

Biological resources are also abundant, for example commercial fishing is a staple of the U.S. Arctic economy that is responsible for about half of all national marine products. [4]

In recent decades, Alaska has been active in advancing tourism, and eco-tourism in particular. Lots of American and foreign holidaymakers head to the only Arctic state for fishing, water and mountain tourism, as well as for skiing and dog and deer sledding. The recreation industry greatly relies on the unique nature of the state, which is home to several nature reserves, the largest being the Arctic National Wildlife Refugee (ANWR).

These vast U.S. Arctic resources are largely untouched and Americans clearly crave to exploit them, although the question then arises of how they intend to combine these two often conflicting principles, i.e. resource exploitation and preserving the unique social and ecological systems. Since development of the Arctic resources has already become an established part of the U.S. political debate, it seems logical to reflect on the discussion and assess its influence on the upcoming election campaign. Of greatest importance appear questions of reopening the oil and gas fields in the NPRA and ANWR, as well as geological surveys in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas.

An extremely wide range of interest groups are involved, from the energy lobby led by transnational majors, to indigenous and ecological organizations, Alaskan political and economic elites and of course federal government.

Energy Lobby

The process’ momentum is largely down to transnational corporations like Shell, ConocoPhillips and Statoil, which have been highly enthusiastic about developing the Arctic shelf.

However, their projects ran into a host of difficulties related to the absence of safe and effective technologies for underwater survey in Arctic conditions. As a result, in 2012-2013 they had to suspend exploration in the Beaufort and Chukchi seas until 2015 in order to decide on efficient methods and ready equipment for future operations.

In early 2015, Shell decided to resume drilling in the Alaskan shelf and in May the same year it received U.S. government permission for drilling six wells 75 miles off Alaska, with work set to begin this summer.

In future, oil companies would also like to continue to develop the continental fields, in particular the reserved hydrocarbons in the NPRA and ANWR. Hence, due to pressure from the energy lobby, in February 2013 the Department of Interior approved the NPRA development plan, which covers licensing geological exploration in half of its territory, and the construction of oil and gas pipelines across its lands.

As for the energy lobby as such, many of its members are not sure about the practicability of further development of Arctic hydrocarbons, at least in the near future, because the steep price drop in 2014 has rendered Arctic oil unprofitable. Nevertheless, corporations believe that when easily retrievable hydrocarbons are depleted and prices go up, polar resources will regain their attractiveness. [5] So, Arctic field development should gradually progress, and the appropriate infrastructure should be developed, ensuring the corporations are fully prepared for a future Arctic boom. Of course, the exact dates are difficult to predict, but many expect the rush to start before 2050. [6]

Civil Society

The energy lobby is opposed by various civil groups, primarily American and international environmentalists like the Greenpeace and native organizations of the Inuit, Athabascan, Gwichin and Aleut united in the Alaska Federation of Natives.

They fully supported President Obama's executive orders banning exploration in the greater part of the ANWR in late 2014 and 2015, and vigorously resist the attempts of Shell to resume offshore drilling.

However, both indigenous peoples and environmentalists suffer from poor coordination and the absence of powerful lobbies in the Alaska State Legislature and Congress. They occasionally manage to obstruct the energy lobbyists’ legislative initiatives, but this group will not turn its back on efforts to access the American Arctic.

Alaska’s Political and Economic Elites

Alaska’s authorities broadly support full-scale onshore and offshore hydrocarbon exploration, working to create an attractive climate for major investors and oil and gas companies, since existing fields will sooner or later be exhausted. According to the Department of Energy, the legendary Prudhoe Bay field’s output is already lagging behind two shale oil deposits in Texas. [7] Hence, dynamic exploration appears timely in order to ensure a smooth switchover to oil and gas production from the new NPRA and ANWR fields. Alaska’s political leaders insist that, for the foreseeable future, the state has no prospect of receiving a source of income that could replace hydrocarbons. Mining and fishing have already peaked, with no prospects for production increasing. Moreover, due to depletion of rare earth metals and marine resources, output may even drop. In fact, the Red Dog mine’s share in global zinc production has fallen from 10 to 5 percent over the past ten years, while the ecotourism vigorously promoted by environmentalists and indigenous peoples will hardly compensate for this revenue gap.

At the same time, Alaska’s authorities stand ready to protect the environment and interests of the indigenous peoples through the possible adoption of a sustainable development concept that would incorporate the economic, social (humanitarian) and ecological aspects. They are confident that, instead of defending their parochial interests, all interested parties including businesses and ethnic groups should launch a constructive dialogue for developing a united approach.

The Alaskan establishment is fiercely lobbying its interests at federal and international levels. In Washington they act through Alaskan senators and representatives, and are led by Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski who heads the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, and who set up the Arctic caucus in early 2015.

Alaskan politicians and businesses are fairly critical of federal Arctic policy both under President Obama and his predecessors, with considerable skepticism expressed about the incumbent president’s ability to honor his pledges on Alaskan development.

As for the Alaskan elites’ international activities, back in the early 1990s the state government initiated a special forum for the interaction of Arctic regions of various countries. In 1991, the Northern Forum was established – an association of Arctic and sub-Arctic countries headquartered in Anchorage. However, the Arctic states’ central governments did little to encourage the forum and sometimes openly opposed its initiatives, meaning that the mechanism of Arctic cooperation became woefully inefficient and has been put on ice.

Then came the Polar Circle, established in 2013 on the joint initiative of Alice Rogoff, an Alaskan activist and editor-in-chief of the Alaska Dispatch, and Icelandic President Olafur Ragnar Grimmson. [8] The Polar Circle represents not only regional and municipal authorities of the Arctic states, but also businesses, environmentalists and indigenous populations.

Given the Alaskan input into U.S. Arctic policy, one may confidently forecast further increase in the state's Arctic focus and continued growth of its input into federal policy irrespective whoever wins the 2016 presidential race.

Federal Government

Obama's Arctic policy is hardly consistent. Under pressure from numerous interest groups, the White House often takes compromise decisions that fail to please the various different parties involved.

For example, this was the case with the late 2014 and early 2015 Presidential Executive Orders on the development of resources in the NPRA, ANWR and the Alaskan shelf, intended to combine preserving Arctic nature and protecting indigenous life through more limits on exploration in the NPRA, ANWR and the Chukchi Sea.

These measures essentially boiled down to a complete ban on oil and gas production in the fragile Arctic areas of the United States, as was demanded by the environmentalists and most of the indigenous population. Despite this, vast areas of the NPRA, ANWR, the Chukchi Sea and Beaufort Sea are still open for licensing geological survey and production of hydrocarbons.

Alaska’s Future: Resource Curse or Sustainable Development

Given the upcoming 2016 presidential election, Arctic resource development is very high on the national agenda. Although proponents of environmental conservation and the development of hydrocarbons exist both in the Republican and Democratic parties, the current debate is definitely oriented around areas of inter-party division.

Democrats, for example Hillary Clinton supports Obama on preservation of the Far Northern resources, as well as protection of interests and way of life of Alaskan indigenous peoples. They insist that the only Arctic state must shake off the resource curse, i.e. dependence on the extractive industries, primarily on energy exports, and focus on ecotourism, hotel and recreational business, as well as high-tech segments – IT&C, transport, science and education.

Republicans agree that the resource-oriented Alaskan economy needs radical restructuring, while the state and the U.S. Arctic should be guided by the concept of sustainable development, which also appeals to realism about the future of the nation's North. They insist that Alaska's economy cannot be reformed any time soon, and the process will be time and resource intensive. Hence, an unbiased assessment is required to determine what Arctic resources should be untapped and incorporated into the commercial turnover with no harm to the environment and indigenous population. The GOP stresses that gradual development of the Far Northern resources, chiefly hydrocarbons, should begin straightaway so that the United States remains in step with other polar countries.

Republicans, including the party’s leading contender for presidency Jeb Bush, blame the Obama administration for ecological populism over the Arctic hydrocarbon issue, in particular for its half-hearted measures on opening the NPRA, ANWR and Arctic shelf for geological exploration.[1] They view this policy as based on electioneering rather than on concerns about the fragile Arctic environment or interests of the indigenous population. Obama is trying hard to win votes among the environmentalist, civic and human rights electorate. Republicans say that the Democratic talk of innovative development of the Arctic economy will remain empty, because neither Alaska nor federal government nor businesses have the money to implement the major plans proposed by the Democratic Party.

If their candidate wins in November 2016, the GOP pledges to fundamentally revise Obama's Arctic legacy and adjust the U.S. strategy for its Far North to the reality and needs of the Alaskan population, big business and the nation. As for the Democrats, they promise to continue the current policy of protecting the fragile Arctic nature and preservation of the ecological balance.

The outcome of the debate is unclear, while the future of the Arctic resources will remain a major issue in the presidential campaign and beyond.

The U.S. domestic debate barely impacts Russian interests, although the Democrats' approach could be of greater use for several reasons. Under the preservation and slow development scenarios for the U.S. Arctic, American and transnational corporation would turn their eyes to Russian Far Northern resources, with Moscow would win another ally in the fight to lift U.S. sanctions against the Russian hydrocarbons sector. Besides, in contrast to the GOP, Democrats profess multilateral cooperation of polar states including Russia on the Arctic Council platform, which is also aligned with Russian national interests.

Charles Ebinger, John P. Banks, Alisa Schackmann.Offshore Oil and Gas Governance in the Arctic: a Leadership Role for the U.S. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 2014, p. 7.

Kevin McGwin. A Clear and Presidential Opportunity // The Arctic Journal, January 28, 2015.

Ebinger et al. Op. cit., p. 7.

The New Foreign Policy Frontier. U.S. Interests and Actors in the Arctic. Ed. By Heather A. Conley. Washington, DC: CSIS, 2013, p. 61.

Lars Lindholt and Solveig Glomsrød. The role of the Arctic in future global petroleum supply // Discussion Papers No. 645. Oslo: Statistics Norway, Research Department, 2011

Lindholt and Glomsrød. Op. cit., p. 30; Production of Hydrocarbons in the Arctic: Risks and prospects.

Top 100 U.S. Oil and Gas Fields. Washington, DC: U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2015, p. 4.

Matthew Lounsberry. Arctic Assembly meets to set rules for exploration, The Washington Times, 2013, October 10; Lesley Price. Arctic’s ‘outer circle’ looking forward to next year, The Arctic Journal, 2013, 22 October.