The Koala between the Dragon and the Eagle

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD in Political Science

Against the backdrop of the USA preserving its status of superpower, and China, which is fast gaining military and political clout, the role of medium-sized nations in the Asia Pacific region is in many cases underestimated. Offering a spectacular example of a balanced, pragmatic approach to formulating a national security policy, Australia can considerably bolster its military and foreign policy potential in the short run and even emerge as a key regional actor. Australia faces a host of economic and political challenges along this path.

Against the backdrop of the United States preserving its status of the established superpower, and China, which is fast gaining military and political clout, the role of medium-sized nations in the Asia Pacific region is in many cases underestimated. Asia Pacific is a multi-polar environment in which the two great powers are engaged in a fierce competition while the mid-sized countries are striving for equality with their senior partners in the solution of regional security problems as well as exploit differences between them in order to protect their own national interests. It is the medium-sized nations that largely define whether better collective security will be developed in the Asia Pacific Region, or whether interstate relations and tensions will aggravate in the years to come. Offering a spectacular example of a balanced, pragmatic approach to formulating a national security policy, Australia can considerably bolster its military and foreign policy potential in the short run and even emerge as a key regional actor. However, Australia, just like many other states, faces a host of economic and political challenges along this path.

Asia Pacific Strategy: The Australian View

Attaching a great deal of attention to national security issues, Canberra is doing its best to timely adjust its military and political strategy to the changing international context. This explains its numerous, regularly updated, strategic documents, such as National Security Strategy 2013, the White paper Australia in the Asian Century 2012, and the Defense White Paper 2013.

Australian leaders clearly understand that, in the decades to come, the strategic environment in the Asia Pacific and, consequently, the country’s national security and foreign policy will hinge on relations between the United States and China. Aware of the existence of American-Chinese tensions, Canberra assumes that the probability of a conflict between these two nations is low, and that in the long term Beijing and Washington will develop a constructive relationship of combined competition and cooperation.

Notably, Australia’s Defense White Paper 2013 differs from its 2009 predecessor as it contains a more neutral assessment of the People’s Liberation Army and Chinese foreign policy ambitions.

Australian military and political strategy highlights the fact that due to the growing importance of the Indian Ocean sea lanes, the growing role of India and greater involvement of Southeast Asian countries in international processes, the Asia Pacific Region offers a template for a new subsystem of international relations within the Indo-Pacific Region. The Indo-Pacific Region concept is far from fresh, as it has been actively studied and developed since late 2000s. Recognized by other states, alongside other elements included in Australia's military and political strategy, the concept is definitely transforming from being the ideological embodiment of Indian foreign policy ambitions into being a valid factor in global politics.

Australian strategic papers also accentuate that in addition to the United States, China and India, the Indo-Pacific Region is becoming increasingly influenced by Japan, South Korea and Indonesia, with virtually no role played by Russia as a Pacific nation.

Although currently there is no direct threat to Australia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, Canberra is eager to maintain and build up its armed forces as the chief guarantor of national security.

Modernizing Australia’s Armed Forces

The latest Defense White Paper suggests that although currently there is no direct threat to Australia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, Canberra is eager to maintain and build up its armed forces as the chief guarantor of national security, with the four key missions being:

- Containing and repelling external aggression.

- Participating in the preservation of stability and security in the Southern Pacific and Timor-Leste (East Timor).

- Participating in Indo-Pacific operations, chiefly in Southeast Asia.

- Participating in operations to attain global security goals.

Recognizing the need to prioritize national security concerns, Australian leaders concentrate on the first two missions above.

Russian and international pundits often interpret the modernization and development of armed forces in the Asia Pacific Region as an arms race, which seems an overstatement. Australia’s military and political strategy proceeds from the thesis that modernizing regional armed forces is not an arms race per se and is more a result of economic development rather than greater inter-state tensions.

At the same time, some of Australia's capabilities, such as submarines, assault landing ships and frontline aircraft, are not up to scratch. As problems related to the rearmament and technological upgrading vis-à-vis other regional states emerged, in the late 2000s Australia launched an ambitious long-term program for the acquisition of a variety of weapons and military equipment, including fifth-generation fighters, non-nuclear submarines, multipurpose assault ships and unmanned aerial vehicles. However, there seems to be a question mark over implementing the program, since the total funding gap in 2009-2022 could reach AUD 33 billion.

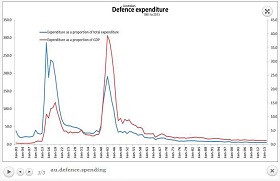

During his 1996-2007 premiership, John Howard made boosting military spending a staple policy and raised it by almost 47 percent in real terms up to an average of 1.8 percent of GDP. Due to the economic crisis and domestic political infighting, the defense budget was cut by five percent in 2010 and by 10 percent in 2012, with its share of GDP dropping to approximately 1.6 percent. The Defense White Paper 2009 envisaged a military budget of three percent by 2017 and 2.2 percent in 2018-2020. For this to happen, Australia's 2012 defense outlays should have amounted to AUD 31 billion, while in reality they hovered at about AUD 26.6 billion, i.e. 14.2 percent less than the figure planned in 2009.

The alliance between Australia and the United States is perceived as a guarantee of resilience to the threats that Australia would be unable to counter alone. Striving to boost its influence in the Asia Pacific and leadership in handling particular regional security matters, Australia recognizes U.S. dominance in relations with its allies.

The Defense White Paper 2013 endorses the previous Labor government’s commitment to increasing military spending up to two percent of the GDP in the long term. The election platform of the Liberal-National coalition under Prime Minister Tony Abbott also provided for a ban on further defense budget cuts and its growth up to two percent of the GDP during 10 years. However, it seems unlikely that the plan will be implemented, since some assessments indicate a figure under 1.7 percent as a minimum until 2017-2018, with a subsequent rapid increase implausible.

The American-Australian Alliance

Canberra’s defense policy is based on self-sufficiency in terms of military potential for national security and defense purposes. However, Australians are quite realistic about their limits. The alliance between Australia and the United States, which includes the American nuclear umbrella, is perceived as a guarantee of resilience to the threats that Australia would be unable to counter alone. Striving to boost its influence in the Asia Pacific and leadership in handling particular regional security matters, Australia recognizes U.S. dominance in relations with its allies.

In 2011, Barack Obama and Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced plans to deploy up to 2,500 U.S. marines on a rotational basis at a base near Darwin in North Australia by 2016-2017. There are currently about 200 marines deployed, but by 2014 this figure should rise to about 1,100. The same year, the sides agreed on easing access for American aircraft to Australian airbases to expand the U.S. air force presence on the continent.

Most Australians approve of the alliance with America, although there is some internal and external opposition similar to that found in American-Korean and American-Japanese relations. Domestic disapproval comes, in part, from the presence of the Pine Gap satellite tracking station on Australian territory. Despite the lack of open protest, Canberra has to repeatedly confirm it is fully aware of the U.S. base’s operations and that they do not infringe on the country’s sovereignty. The deployment of American marines near Darwin also generates disapproval in Australia and beyond, with fears also expressed by China and Indonesia.

Australia is therefore compelled to balance between the need for a stronger alliance with the United States and the threat of becoming hostage to Washington’s foreign policy, which risks damaging its national security and other interests. The relationship is somewhat unequal as U.S.-Japanese relations are. Australia counts on guaranteed U.S. assistance if a major national security threat arises, but at the same time it is not ready to back America blindly, particularly in a serious confrontation with China, which has been its largest trade partner since 2007 accounting for about 30 percent of Australian exports and about 18 percent of imports.

Defense and Security Cooperation with other Asia Pacific States

The risk of “balkanization” in the Southern Pacific is of particular concern to Australia’s leaders. As a result of the Fiji coup and volatility in the Solomon Islands and East Timor Australia’s military-political language saw the development of the term term “arc of instability”.

Australia’s defense and security depends to a great extent on ensuring a constructive environment in its vicinity and on its borders, on the island territories that belong to it, in the vast territorial waters, exclusive economic zone and sea lanes. Canberra unambiguously names the Southern Pacific as an area involving its vital interests, aiming to prevent it becoming a source of threats to national security and home to military bases for potentially hostile states.

The risk of “balkanization” in the Southern Pacific is of particular concern to Australia’s leaders. As a result of the Fiji coup and volatility in the Solomon Islands and East Timor Australia’s military-political language saw the development of the term “arc of instability”. Weak and failed states in the region are a breeding ground for international terrorism, extremism, piracy and other threats to Australia’s national security. Although in recent years the arc of instability concept has been criticized by security optimists, Australia’s military-political strategists prefer not to underestimate the challenges.

Australia is doing its best to exercise a mild protectorate over the island states in the Southern Pacific, specifically through the maritime security program that provides for the free transfer of patrol boats to countries that have already received Australian Pacific-class patrol boats under the Pacific Program of the 1980s-1990s.

President of the Republic of Indonesia meets

with Australian Prime Minister

Canberra initiated the first meeting of Southern Pacific defense ministers in Nuku'alofa, the capital of the Kingdom of Tonga. The event brought together representatives of Australia, New Zealand, Papua-New Guinea, Chile and France, and the US along with the UK attended as observers since they support Australia’s policies to strengthen its position in the Southern Pacific. Despite poor presence of regional states and significant participation of outside states, the forum has set ambitious goals, the key one being to build mechanisms for multilateral cooperation in the interests of security in the Southern Pacific under Australia’s informal leadership.

In view of regional problems and Canberra's aspirations for regional leadership, Australia’s planned armed forces modernization naturally envisages better assets for high- and low-intensity military operations including peacemaking and humanitarian missions. Successful interventions in East Timor and the Solomon Islands, which stabilized the situation and considerably lowered domestic tensions for successful elections in East Timor, have only strengthened Australia’s commitment to active engagement in making the region more secure, and its commitment to ensuring it has the capacity to respond promptly to crises in the vicinity of its borders.

Australia is now entering a new stage related to its departure from major overseas operations. Less overseas engagement should help Australia concentrate on developing and strengthening its military assets with the goal of enhancing its own security and defense, and that in its close proximity.

The economic and military-political importance of the Malay Archipelago, with its numerous sea and air routes is pushing Australia into close partnership with Indonesia, whose role in Canberra’s foreign policy has long been controversial. On the one hand, Australians have perceived Jakarta as the most likely threat to national security, while on the other they officially recognize it as a key strategic partner. In 2012, the two states signed the Defense Cooperation Agreement to augment the 2006 Lombok Treaty. The 2012 accords provide for bilateral cooperation in counterterrorism, maritime security, peacemaking and intelligence exchange.

Australia is cautiously approaching Japan, South Korea and India on a bilateral and multilateral basis, and is also developing cooperation with other small- and medium-sized nations in the Asia Pacific Region.

To this end, in 2012 Australia signed the Memorandum on Understanding for Defense Cooperation with Vietnam. The Australia-Philippines Status of Visiting Military Forces Agreement came into effect the same year. In order to mitigate policies aimed to curb China’s growing military potential, Canberra is working towards further developing its partnership with Beijing. Despite the obvious rationale underlying this approach, it cannot but generate certain fears in Washington – which is already insecure over what support it can expect from its allies if a conflict or serious confrontation with China arises.

Alongside developing bilateral defense and security ties, Australia also gives a great deal of attention to multilateral dialogue and cooperation, specifically within the Five Powers Defense Arrangements and ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting Plus formats.

Since the withdrawal from Vietnam in the early 1970s and the East Timor operation in 1999, Australian forces have stayed out of major military campaigns, with scant importance attached to combat training and support for the national defense potential. However, in the late 1990s the situation changed. Under the Defense White Paper, Australian forces have taken part in about 100 missions abroad since 1999, with about 3,000 servicemen participating in 14 campaigns at the moment, the key ones being Afghanistan, East Timor and the Solomon Islands, and the Combined Maritime Forces.

Australia is now entering a new stage related to its departure from major overseas operations. In 2012, Canberra wrapped up the East Timor operation, and is winding down its presence in Afghanistan and the Solomon Islands. Less overseas engagement should help Australia concentrate on developing and strengthening its military assets with the goal of enhancing its own security and defense, and that in its close proximity. At the same time, the 2013 Defense White Paper stresses the need to retain the experience in counterterrorism, maritime security, peacemaking, humanitarian and other functions acquired during these overseas operations.

Hence, Canberra is working hard to advance its military and political potential and to strengthen its influence in the Asia Pacific Region, primarily in the Southern Pacific, through an ambitious modernization and rearmament program for its military forces and through the dynamic development of military and political partnerships with Asia Pacific countries. Aiming to secure the status of a self-sufficient regional power, create a favorable international environment, and ensure protection and mild control over its zone of influence, this policy entails numerous problems, ranging from funding from the armed forces and maintaining a balanced position vis-à-vis Beijing and Washington.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |