A Hazardous Game – The Strait of Malacca

In

Log in if you are already registered

In the last decade our portrayal of high seas has been encapsulated by a steady line of Hollywood blockbusters, which focused on damsels in distress and merry pirates that came to their salvation. But as with most modern films, reality is far from fiction. If Jack Sparrow was around today he would ditch the balmy Caribbean and sail to Asia. As in Asia, an economic marvel has transpired along an explosion of vast riches for opportunists. However, aside from meeting other pirates, Jack would soon learn that he has entered one of the most vital and fiercely contested waters of the seven seas. He would grasp he has been embroiled into one of the biggest geopolitical chess games, except all the pieces are real and the consequences of a checkmate are colossal. Hence, in this post we explore what makes these waters so important and potentially volatile. Please Enjoy & Feel Free to Comment!

In the last few months I have received numerous emails and comments over my social networking platforms insofar as exploring the issue of the Malacca Strait, since I first mentioned it in my post “Wary Bear and Shrewd Dragon”. As a matter of fact, it was one of the key issues we discussed with Dr. Mitrova, but due to its intricate nature and sheer number of players involved I decided not to add it into that original post. Now it is time to revive this topic with already explored ideas and fresh research. I am using the Malacca Strait in a loose sense as I not only discuss the geographic local, but also the wider vicinity and what is known as the 'Malacca Dilemma'. To those unfamiliar with the strait and question its value, it is worth noting that ~70,000 vessel sail via this shallow 500-mile passage, which makes it the busiest seaway in the world based on capacity and second busiest based on trade volumes after the Dover Strait in Europe. In fact, ¼ of global trade passes via Malacca making it a vital connection between the Eastern and Western world. A stipulation that makes this route more strategic is that ~15 million barrels of oil pass there daily or 1/3 of the global oil trade, as tankers move from mainly Middle East to Asia (China, Japan, South Korea, etc.) It is not the only passage available there (e.g. Lombok-Makassar [used by super-tankers] or Sunda Strait [very shallow]), but it is currently the most economically feasible for the region (Khalid, 2009; Casey & Sussex, 2012). I predominantly focus this post on China with first section directly referring to it, then second part looks at other players and finally last piece adds non-state players (e.g. pirates/terrorists), but, feel free to comment as there is a lot to indulge in!

In my second interview with Dr. Mitrova it quickly became obvious that an accidental or induced blockage in the Strait of Malacca would lead to severe repercussions for China. Dr. Mitrova recalled from her own well-travelled personal experience and top academic literature that this is a colossal concern for Chinese policymakers, military circles and this issue frequently surfaces in business discussions. In early 2003 things particularly heated up as Hu Jintao warned that certain “large nations” were trying to “control the transportation channel at Malacca”; which led to the instigation of the unofficial “string of pearls” strategy, whereby naval presence was raised and military bases were built (Telegraph, 2011). It was unofficial as the term actually came from a US consultancy firm that quickly caught on, but this still does not take away from the clear shift in the region towards militarization (Chatham House, 2012). Later in 2003, Hu Jintao repeated his wish to the Communist Party as the “Malacca Dilemma” must be solved as this “oil-lifeline” is a major flaw that could see the entire state collapse in a matter of weeks (Yergin, 2011: 209-211). Characteristically, China used diplomatic language and did not refer to the USA when speaking about 'large nations', but no one could be fooled as this red dragon was referring to the 7th Fleet of the US Navy.

From 2003 onwards tensions continued to fume as China felt that this bottleneck was an Achilles’ heel in seemingly impermeable Chinese mainland. Characteristically, just this time for Washington, little was done to ease tensions, but instead stacks were laid for a spark of fire. Increasingly Washington’s policymakers reflected more vividly the neorealist language, which was finding its way across the hallways of US institutions. If we scan the leading neorealist publications (Walt, Mearsheimer, Layne, Posen, etc.) we would quickly find the common denominator or strategy of “offshore-balancing” China (Foreign Policy, 2011). The neorealist scholars, strategists and officials realise a land war with China will be suicidal, even if USA’s technological lead narrows the population disparity; therefore the only realistic way to limit its foe is via clogging up its major artery. It was evident that tensions especially took-off as USA pulled out of Iraq and finalised Afghan departure; as if a new major foreign theatre was needed. In Australia 2011, President Obama made a notable speech that periodically referred to USA as a Pacific nation that has a long-term role in shaping the region and making sure that all play by the 'rules' (White House, 2011). Moreover, in 2012 then Defence Sec. Panetta outlined a strategy that would see USA’s fleet of 285 ships divert from its equal divide amid the Atlantic and Pacific, towards the latter’s 60% outweigh by 2020 (WSJ, 2012). At the end of 2012 Obama again relit a match previously sparked by Bush, as during the presidential election debates he said that “China is both an adversary, but also a potential partner in the international community if it’s following the rules” (CNN, 2012). One appreciates Obama was under pressure for seeming soft in contrast to trigger-happy McCain, but these words would ring in the ears of China’s elite. As why would China eternally follow the 'rules', which are made by and for the hegemon, particularly if China becomes the world’s biggest economy?

As Yergin (2011) stresses oil has been a primary energy concern for China ever since Mao, as it was perceived as a main component of a modern economy, in turn, fuelling military and political muscle. Yet, in the 20th century China has experienced repeated cuts like: during the Sino-USSR split, USA’s off the record embargos when it was a major exporter, official oil cuts during the eruption of the Korean War and meddling by an old rival Japan (Ibid). Hence, it is unsurprising that China is wary of any future issues like Malacca, via which ~80% of its crude imports inflow. To nurture this sore China has kept a prolonged strategy of “multiplying its foreign linkages and reducing dependence upon any one partner”; whilst also varying supply routes via land and sea (Blank, 1991: 649-51; 2010). I have explored some of these partners in my older post (e.g. Central Asia or Russia; see: China Post), but extent of success via diversification depends on a heap of reasons. A lot will be down to future growth in demand, amount of oil needed to make $1000 of GDP (currently falling, which is positive), stability in other states, domestic output and so on. Still, China is calculated and will not abandon things to luck. In the 10th five-year plan (2001-2005) it has instigated an ambitious tactic of a strategic oil reserves program (SPR), under which it can withstand an oil blockade for up to 40 days from 2011 and up to 90 by 2020 (EIA, 2013: 12-13). One expects these targets will be typically overachieved and perk up the mere 21 days it could have lasted prior to the plan. By 2020 the Chinese capacity will be similar to the global level and allow flexibility without a need to incessantly import without a single disturbance (e.g. in days: Japan 169, USA 158, Germany 117, France 96 (Li & Cheng, 2006)).

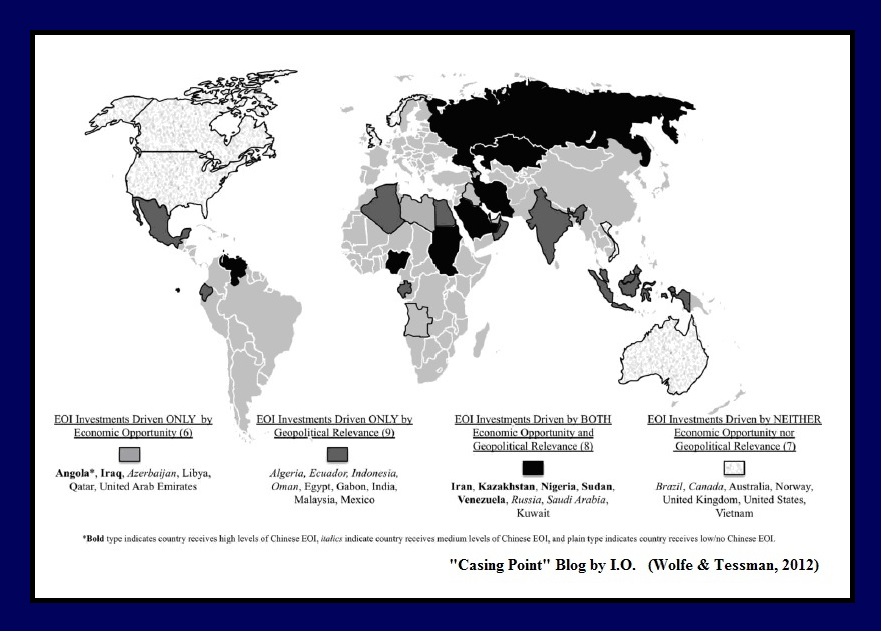

At this stage I want to add about China’s interests in other states to attain crude oil. I found Wolfe and Tessman’s (2012) piece to be notable as they concur my prior post’s analysis that China is keen on equity investment which gains exploration/drilling/infrastructure rights, secures a guaranteed production percentage or acquires entire firms, while adding points I am yet to say. They stress that China’s majors (CNPC, Sinopec and CNOOC) have become increasingly dynamic in dozens of nations due to a state policy of “going-out”, which is a result of a stagnating domestic output, increasing demand and the Malacca Dilemma. Moreover, these majors favour unstable states with high corruption as this way competition from international oil firms is minimised which allows 'strongholds' to be build. Essentially, they follow an altered business culture, as they do not have shareholders in a common sense, which allows them to be opportunistic. To an extent, 'business is just business' and high-risk is accepted as there is near endless assistance from Beijing that is well known for 'deal sweeteners' which lure corrupt officials. However, we should not see these majors as 'locking-up' resources nor that they are immoral (as it is trendy to bicker online), as in reality they have little choice and China anxiously needs oil as the memory of early 2000s energy famish is still fresh. Basically, China cannot trade with OPEC smoothly as it does not give special treatment via some sort of guaranteed quotas and rivalry is fierce from traditional majors who have cemented their place over the past century. Moreover, Russia opposes equity investment and it is not corrupt to an extent that it sells major assets, nor can China engage Europe or USA as that is a political minefield.

If we recall in 2005 CNOOC tried to buy USA’s Unocal, but it failed spectacularly, as liberal mottos proved not as free as they sounds. Yergin (2011: 204-205) described the attempt well by saying that it was like – throwing a lit match into a gas filled room on top of Capitol Hill, as it instantly flamed a debate over energy security. So to put it crudely China is not allowed to buy firms so that it can import high-end technologies to better its domestic production (even if a firm like Unocal accounts for a mere 1% of the US output), nor can land adjacent Central Asia support its growing energy demand fully or Russia be prepared to play on its terms. In effect, China is left with investing in second-tier opportunities and the Malacca Dilemma persists with just a balancing effort trying to minimise rise in dependence. Li & Cheng (2006) see that options are limited as energy demand in Asia is growing at an annual rate of over 3% and already more than a half of world’s oil and almost 2/3 of gas pass via the strait, thus it is hard to see how these sums will be circumvented. Still, when Li & Cheng wrote their work, trade with Russia was slow, but recently non-equity investments have occurred. So, if China continues to alter its pose it may well engage Russia as it is the most appealing long-term supplier. Russia holds huge oil/gas reserves, which are geographically close as it takes just 3-5 days for East Siberian oil to flow to China, in contrast to two/three weeks from the Middle East (Voice of Russia, 2012), and also as an added bonus US or NATO cannot defy Russian and Indian airspace to target future pipes.

The prior paragraph hints about a possible alignment among China and Russia, but a lot will depend on how circumstances will change and the balance of power within the region. Also, a big question will hang over the heads of Russian policymakers, as will they want to aid an Achilles’ heel of such a strong neighbour and vitally on what terms? On the bright side for Russia, even if China addresses the problem of Malacca Dilemma by naval supremacy and construction of its odd “island aircraft carriers”, like the ones on Mischief Reef or in Spratly Islands (Raine, 2011), it cannot do so all over. The Strait of Hormuz will just take the place as the next dilemma. Joseph Braml of the German Council on Foreign Relations said the basis why USA’s 5th fleet is staying in the Middle East (even though oil shale may make USA independent from the area) is because it allows the Chinese energy tap to be shut off if needed (Spiegel, 2013). So in all China will need to play its pieces in advance, but some moves may well be forced upon it.

In the discussion above we have focused predominantly on the great powers play, but lesser powers will also influence the distribution of power and possible consequences. Malacca’s littoral states like Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore will also play a major role and all three have increased expenditure on naval hardware. The biggest push has been made by the tiny Singapore with sizeable investment in submarines, which now account for 5 out of the 9 in the area. Indonesia in 2011 also tested the Russian made Yakhont (P-800 Oniks) anti-ship/anti-aircraft carrier supersonic missile with a 300 km range, as it and other regional players bid for “game-changing” weapons (Tan, 2012). In this game being covert is vital; navies afford governments the means of exerting pressure vigorously but less dangerously or unpredictably than other forms of force as the freedom of the sea makes them locally available whilst leaving them uncommitted (Ibid). Interestingly, USA’s calls for involvement have been rejected by Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia quite consistently as they see security as their duty (Li & Cheng, 2006: 578). It is unfortunate that Obama’s planned visit to the region’s APEC meeting had to be cancelled due to Congress’s inability to formulate a budget (BBC, 2013). As this could have hinted where we stand now and whether China’s increasing surefootedness made these countries less defensive about their own sovereignty when dealing with the US.

Still, we should not see Singaporean, Indonesian and Malay stances as equal, as their perceived security threats and capabilities to address them are different. The latter two least favour USA’s and Japanese involvement in regional matters due to fears of their sovereignty diminishing. In contrast, Singapore is keener due to its lesser size and the fact that it is enmeshed as an energy transit state. Not only does most of Asian energy flow via its docks, but it has Asia’s leading refineries. As a result, it could potentially receive the most pressure in case of any problems. At this point it is worth reflecting on my older post – Social Sciences in the Mist. As again we face an academic hitch as scholars have avoided looking into this key transit state with most focusing on 'sexier' topics of Ukraine and Belarus, but such pipeline literature is not helpful to seaborne deliveries (Casey & Sussex, 2012). In the research that is done, most look at energy matters in a passing manner as one of the key issues, but without much detail. I found that Khalid (2009) summarises the feeling of these literal states quite well as they see that most global players behave immorally as they 'free ride' and abuse the passage by not offering enough monetary aid yet expect a right of passage. Khalid also offers a good summary of all major initiatives in the strait, but recalls just one model example of financial aid in 1981, when Japan granted 400 million Japanese Yen for clearing up possible oil spills. In contrast, a lot of support from China, USA and Korea had to be cast off as it was basically conditional and impinged sovereign rights.

To end this section where we begun, the way these smaller states act will depend on major powers. Raine (2011) argues that China has made impressive overall progress in improving relations with its neighbours, but we still see mounting tensions. In the South China Sea – China, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam vie for the three million square kilometres of territory and there is definitely something in the water. At the moment no one quite knows the scope, but these waters contain a lot of oil and gas, which led to a myriad of incidents. In 2007-08, Vietnam’s cooperation with ExxonMobil and BP was derailed after China’s wrath. Also, ships of several oil majors were escorted out or even assaulted when attempting to survey the waters. In 2012 a peculiar action was taken by China to add the map of its territorial claims to Chinese passports; it is fair to say that other states were infuriated, particularly as the claim involves almost the entire sea and crucial oil/gas fields in the south, near Brunei (Financial Times, 2012). Major and even petty actions wane China’s charm offensive and at one stage may grant the US sufficient excuse to get involved, which China is most against. The Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi said at the ASEAN Forum in July 2010 that Beijing is unhappy about Washington 'internationalising' the region and prying at a party without invitation. In all, China faces a tricky game of manipulation as it cannot be inert as it is constantly fighting energy shortages or strain from rising prices for its 1.35 billion people, but too much action may break the thin layer of ice it is walking on. As Raine (2011: 79) also adds many policymakers and members of the Chinese elite see these waterways as a “test base”, which if succeeds will allow China to “safeguard commercial interests and world peace”.

In this final part we ought to examine pirates as I started this post with Jack Sparrow, though, I must admit that was a luring factor into a serious global debate. As Deng (2010) points out piracy was common in Asian waters since the 14th century and from 1520-1810 it even outweigh states power. As nationalisation alongside militarization has evolved, piracy has gradually altered to become more organized, but at the same time brutal (see Petro-Ranger Story: NYT, 2000; or Cheung Son Tragedy: ABC News, 2001). It is unsurprising that the Strait of Malacca is popular with pirates as it is ~900 km long, just 5.4 km wide, with shallow depth of ~25 meters, while topographically it offers a lot of shelter. Still, a further alternation and then decline of piracy has taken place after the nirvana years of 1992-2005 (when ~2500 attacks were traced and five times that figure is estimated to be unreported); attacks fell as littoral states started patrols from mid-2005 (Li & Cheng 2006; ICC, 2013). It is hard to predict if attacks continue falling, as if we recall earlier point, these states may ditch the dear patrols due to free riders not footing any of the bill. To highlight, a lot of funding is needed as just in Malaysia there are 32,672 licensed fishing boats and many with no documents, which allows for stealth as 4 out of 6 attacks in the region are carried out with the use of fishing boats (Bateman et al, 2007). At the same time, littoral states do not want to see state navies of China and USA to get involved due to sovereignty fears. It will be thus vital to see how regional coast guards develop alongside bilateral legislation as pirates can not only escape in boats, but also in courts due to a myriad of loopholes.

I recommend having a look at the tremendously well researched piece by Bateman et al (2007), as it details the ships types and the possible risks from piracy, terrorism and alike. To offer some headline numbers it is interesting to highlight that 36.9% of all global ships are oil tankers, which is just in front of normal dry bulk carriers (36%). Insofar as Malacca, in 2006 a total of 22,995 oil tanker journeys were recorded via the strait, which is only second to 29,672 container vessels, as we know Asia is a leading producer of low-cost consumer goods. Also, in the last decade the world has recorded an upsurge of LNG tankers with Indonesia, Malaysia, Qatar and Australia shipping liquefied gas via Malacca to Japan and Korea. In all, most ship types are growing in demand with Khalid (2009) even underlining that by 2020 Malacca will see traffic of 100,000+ ships by modest estimates. This is a major worry as it compounds the fact that the funnel-shaped Malacca contains several narrow passages, sandbanks, shoals and shallow areas which pose challenges to navigation. One wonders whether it is a good idea to mix so much traffic and huge tankers together, as essentially we create a massive floating bomb in an equivalent of a small bathtub.

Bateman et al (2007) underline that contrary to belief damaging a tanker is difficult as it is not an easy RPG job by a half-witted pirate or a crazed terrorist. The 1980s tanker wars between Iraq and Iran showed that sinking such vessels is challenging even for professionals. A natural defence mechanism of such vessels is their size and nearing them in small boats is suicidal if on a move. Also, as global shipping becomes more large scale, the cost will increase per unit; for example a large LNG tanker costs $300 million which makes it an incredibly prized asset, allowing firms to invest in security and heighten onboard rules on top of already specially reinforced hulls and composite materials. In essence, such ships can only be high-jacked if anchored and even in this case due to skill required to sail them an abordage by an unskilled crew is unlikely to be effective in relocating the ship somewhere else. Also, as tensions have increased in Malacca following 911 and a video found in Afghanistan of a terrorist group tracking oil tankers, there is heightened communication between ships and ports making large ships difficult targets. This raises the question who gets pirated? Well, it is typically smaller product tankers that carry refined oil or ready products which can be easily sold on a buzzing Asian black market. If worst comes about with even a small tanker sinking in one of the Malacca shallows, it will result in over 50,000 ships being re-rerouted for over a year (Li & Cheng, 2006), which will destabilise not just the region, but also the global economy. However, we hear less about traffic jams, pesky pirates, or environmental degradation, in contrast to major powers flexing muscles, so if there are a problem in the future it will be addressed as naturally unexpected.

The above post provided just a glimpse of the tensions and problems that inhibit these waters and hinted at the vital importance of this strategic route. We have seen in the recent years a subdued US pose towards China, which is not a coincidence as the superpower’s foreign muscle is undermined by its weak economy (which perhaps was unhinged by its foreign policy in a revolving-door effect). However, if USA reignites and hard-line neocons get in office as almost cyclically expected, relations with China will cool. USA has always prided on being the leading state, so it is hard to imagine that it will just sit back and allow President Jinping with his parodied 'Chinese Dream' and China in hand, to just to waltz past (BBC, 2013). It seems, this area will be where the geopolitical game will be played for the foreseeable future, be it as a test-bed for China or off-shoring policy for the US. Maybe we ought to welcome such rivalry and its resurgence in geopolitics - if we adapt an accepted principle that in business a supreme practice is reached via competition. We should not forget that the reason the Cold War period remained relatively calm, was because USA kept USSR in check, while USSR kept USA bounded. If a similar setup existed in the 21st century maybe its countless wars would be avoided. The recent and now famous OP-ED, by the Russian President in NYT, hits the nail on the head as it is dangerous for anyone to see themselves as exceptional and more parity may well be desirable (NYT, 2013). However, these are wide and vital questions we ought to ponder, so please feel free to leave a comment with your own opinion!

P.S. if anyone wishes to get any of the above material, please drop me a line in LinkedIn.

Thank You for Reading & I hope You've Enjoyed this Post!

Igor Ossipov

M.A. University of Kent & Higher School of Economics, Oil/Diesel Broker and RIAC Blogger.