The Catastrophe of 1914: Russia's Choice

5th July 1914

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Doctor of History, Assistant Professor at St. Petersburg State University

Only now, one hundred years after the July Crisis of 1914 that triggered World War One, we have a complete picture of the events that occurred. Although scholars enjoy access to numerous sources of all types that document practically every step taken by the rulers, politicians and generals instrumental in turning the crisis into war, debates over the outbreak of the conflict are still in full swing.

Only now, one hundred years after the July Crisis of 1914 that triggered World War One, we have a complete picture of the events that occurred. Although scholars enjoy access to numerous sources of all types that document practically every step taken by the rulers, politicians and generals instrumental in turning the crisis into war, debates over the outbreak of the conflict are still in full swing.

The War: Incidental or Inevitable?

The succession of the events in July 1914 has been extensively analyzed, but the true causes are still debatable. Some historians believe that diplomats were merely short on time to settle the matter peacefully, while their opponents insist that war was an inevitable outcome of a crisis that followed numerous and diverse tensions between the great European powers over several decades.

Accepting that the war’s timing was random is not beyond reason. Austria-Hungary used the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914 in Sarajevo as a pretext to create conflict, although under an alternate scenario, the alleged reasons for war could have been quite different. The point about the inevitability of the war requires much more profound examination.

In fact, geopolitical, economic and other disagreements were escalating, but the risk of war was also increasing because warfare was seen as an effective and, more importantly, a quite acceptable method for resolving disputes.

The answer is not at all clear, but the abrupt increase in the probability of war in the early 20th century was obvious, with Europe permeated by a network of military and political alliances. The Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy was opposed by the Russian-French bloc. In 1904, the Anglo-French treaty or Entente was signed. In 1904-1913, this arrangement was regularly shattered by international crises, each of them marked by major hostilities. "The clash of the nations in Europe appeared unavoidable in the more or less near future, the atmosphere becoming more strained with each day," wrote in his memoirs wartime General Yuri Danilov, who occupied a number of top positions [1]. But it was not just the accumulation of tensions between the states and the military-political alliances. In fact, geopolitical, economic and other disagreements were escalating, but the risk of war was also increasing because warfare was seen as an effective and, more importantly, a quite acceptable method for resolving disputes. At the time, not a single party seriously expected that the war would last years, with the strategic plans of great powers allotting two to three months for the active phase required to inflict decisive losses on the enemy and emerge as the victor.

In the 19th century, Europe plunged into a massive buildup of its armed forces, those of a new type based on a universal draft and which entailed a new system of nonstop military planning; preparations for war were now routine. States were making strategic plans even when war was unlikely, because in case of hostilities, time was limited to complete mobilization, ensure the procurement of the forces with reserves and materials at levels much higher than previously needed, as well as their arrange for their transportation to the war’s theater. By 1914, the Triple Alliance and the Entente were already extensively practiced in strategic planning against each other, only creating the illusion that the action was going to be smooth, swift and victorious, with no surprises complicating their forces’ advance.

Hence, it was the overall belief in the effectiveness and acceptability of warfare for resolving problems that made the fight unavoidable, or at least highly probable, in a situation when one party sees the environment as suitable for launching an attack.

Strategy and Diplomacy in the July Crisis

In the 100 years prior to WWI, the European great powers had formed and extensively employed a system of crisis resolution, resting on multilateral diplomacy known as the Concert of Europe, with congresses, conferences and meetings convened to present their interests and balances of forces as well as reach compromises in the end. While marked by some failures, the arrangement was nevertheless satisfactory in preventing wars between the great powers, even when the opposing blocs lined up on both sides, for example during the 1905-1906 Moroccan Crisis or the First Balkan War of 1912-1914. However, Russia's attempts to engage in multilateral diplomacy for the peaceful resolution of the crisis in July 1914 encountered stubborn resistance, primarily from Germany. Kaiser Wilhelm II and his top brass regarded the situation as strategically advantageous for the Central Powers, but prone to deterioration in the near future, which pushed them towards war for resolving the snowballing disputes.

In the 19th century, Europe plunged into a massive buildup of its armed forces, those of a new type based on a universal draft and which entailed a new system of nonstop military planning.

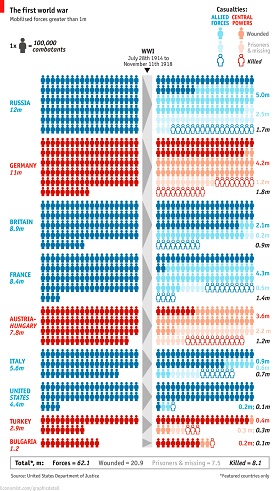

In fact, the balance of forces really seemed to favor Germany by late 1913, which had managed to successfully complete a number of improvements to its armed forces ahead of schedule. The Germans were obviously leading in the ground forces race. In the period of 1910-1914, the strength of the German regular army grew from 622,000 to 800,000, while full mobilization could deploy a regular army of 3,685 million servicemen. The allied Austrian-Hungarian army could reach 2,080 million through mobilization; Russia was able to put up 3,516 million and France – 1,735 million. The modest British land forces possessed only six divisions for deployment on the continent at the war’s outbreak [2]. Taking into account their technical advantages and effective communications, German superiority appeared overwhelming.

Russia and France tried hard to catch up with their rival, but failed to keep pace. Responding to their neighbor's preparations, in 1913 France adopted a law extending military service from two to three years in order to significantly build up their regular army quickly (see the Law at. But the focus was actually on Russia, whose defense capabilities had been undermined by the defeat in the Russian-Japanese War of 1904-1905, by the revolution and the subsequent economic crisis. At the same time, the threat of a major European war was on the rise, propelled by economic factors. In addition, a special commission of the Main Artillery Directorate analyzed the lost Japan war and later the Balkan Wars only to find that a relatively concise and short modern war would require military materials in volumes greater than the previous campaigns.

Thanks to a stabilized economy and slow economic growth, Russia kicked off the rehabilitation of its fighting capacity by laying down four new battleships for the Baltic Sea in 1909 and launching a navy development program to start the construction of various ships. In 1913, the government adopted the Minor Program and in 1914 – the Major Program for reinforcing the army through force reorganization, adding more infantry and cavalry, as well as significant improving the artillery by 1917.

In the summer of 1914, these strategic calculations pushed the Austrian-German bloc to make use of this suddenly available pretext for taking action and undercut diplomatic efforts for resolving the crisis.

As a result, by 1914, Germany was still ahead in its development of ground forces, but was running the risk of losing its dominance over time. The future of Austria-Hungary, its key ally, appeared murky. With domestic problems piling up, the Patchwork Empire might collapse. Germany was behind Great Britain only at sea despite titanic efforts to draw level. But the German-British thaw in 1912-1914 made Berlin believe that the Brits would stay away from the emerging collision [3]. Hence, in the summer of 1914, these strategic calculations pushed the Austrian-German bloc to make use of this suddenly available pretext for taking action and undercut diplomatic efforts for resolving the crisis.

Russia at a Crossroads

Russia suggested that the great powers jointly consider the matter in order to find a compromise, while the situation required some time and the Austria-Hungary government limited the Serbians to only 48 hours to respond.

In this most complicated environment, Russia was forced to make the decisions that determined the future of the conflict. The ultimatum presented by Austria-Hungary to Serbia on July 23, 2014 ruled out meeting demands in full. After the Serbian rebuff, Austria-Hungary expectedly began preparations for war. Serbia was waiting for advice from its ally Russia and wanted to know which steps to take should the conflict escalate. Russia was faced with a thorny dilemma. On the one hand, by promising assistance to Serbia, Russia was risking a war against the Austria-Hungary bloc with the reorganization and modernization of its forces still incomplete. On the other hand, without Russian help, Serbia could not resist the offensive and would lost the entire Balkans to the Entente. After defeating the Serbs, the Austria-Hungary alliance, already bolstered by the Ottoman Empire, could perhaps attract new members in both Bulgaria and Romania, and possibly Greece and even Italy.

At a meeting on July 11(24), 1914, the Russian Council of Ministers appeared to have taken a decision worth the wisdom of King Solomon [4].

Ministers on the cover of "Iskry" Magazine

Efforts of Mr. Sazonov, supported by French Ambassador Georges Maurice Palйologue and Alexander Benckendorff, Russian Ambassador in London, failed, as the British government lingered and adopted the joint approach too late.

First, Russia made its final attempt to employ the system of great power consultations in order to compel the Austrians to postpone military action. Russia suggested that the great powers jointly consider the matter in order to find a compromise, while the situation required some time and the Austria-Hungary government limited the Serbians to only 48 hours to respond. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov tried to get a postponement even before the meeting and appealed to Austrian-Hungarian Foreign Minister Count von Berthold and German ambassador in St. Petersburg, regrettably in vain.

Second, in order to avoid a large-scale European war, in case of the aggression from Austria-Hungary and the inability to defend its territory, the Serbian government was recommended to "surrender if an invasion takes place and declare that Serbia was yielding to force and entrusting its destiny to a decision of the great powers." [5] Diplomatic interference by the great powers to end the war appeared plausible even if the collision was to break out. Russia's involvement, the worst-case scenario, was prescribed only by item three of the Council of Ministers' decision which envisaged applying to the Czar for permission to launch the mobilization of the Kiev, Odessa, Moscow and Kazan military districts, as well as the Black Sea Fleet. The Czar agreed to do so, adding the Baltic Fleet. The illusory hope to limit the war to the Balkans was to be seen in the decision to keep the Warsaw and Vilna military districts off of the list.

One more opportunity to avoid fighting could be found in the evaporating German illusions about future British noninterference. The German Emperor was not so sure about the strategic advantages of the Triple Alliance. To make it happen, Russian diplomats counted on assistance from France, Russia's main ally. French President Raymond Poincarй visited Russia on July 20-23, only to once again demonstrate the inviolability of the Russia-France alliance. However, the efforts of Mr. Sazonov, supported by French Ambassador Georges Maurice Palйologue and Alexander Benckendorff, Russian Ambassador in London, failed, as the British government lingered and adopted the joint approach too late.

Unwilling to plunge into the war when its ally was unprepared, Serbia agreed to meet all the demands, only gently rejecting the point about Austrian access to Serbia's territory for investigating the assassination. This was enough for Austria-Hungary to declare war on Serbia as early as on July 28. The Serbs ignored Russian advice and fiercely repelled the aggression. Soon, strategic considerations finally put diplomacy on the backburner and the mechanism of alliances was in full force. Russia launched nationwide mobilization instead of a partial draft, proceeding from the quite sensible reasoning of the generals that the country would inevitably face both Austria-Hungary and Germany, while the peaceable messages from the German Emperor were meant only to gain time for attacking France.

Following Russia's refusal to stop its mobilization, on August 1, Germany declared war on Russia. France even did not try to step aside, realizing that if Russia was beaten, it would follow suit. Paris refused to guarantee the Germans noninterference, so Berlin also declared war on France, with the Balkan conflict swiftly morphing into a world war.

The escalation of the summer 1914 crisis had its specific and innate logic that pushed governments to certain conclusions. Russia's involvement was just one stage in the chain reaction developed over decades and triggered by the decision of the Central Powers, i.e. Germany and Austria-Hungary, to use the Sarajevo assassination as a pretext for military action. Russia's attempts to prevent the clash were futile due to a shortage of time and they failed to dissuade the Austrian-Hungarian bloc from using their assumed strategic advantage. As a result, the initiators of the war were absolutely sure about the need for swift attacks to prevent diplomats from launching the multilateral crisis management machine. On the other hand, its own strategic interests also restricted Russia's room for maneuver, since it was unthinkable to put up with the defeat of its key ally in the Balkans, so that in the long run, an environment emerged for a crisis to unavoidably grow into a war.

1. Danilov Yu.N. Russia in the World War 1914-1915. Berlin, 1924. P.1

2. See the strength of armies assessed by the Russian Chief of Staff in the book From the Portsmouth Peace to World War One by Shatsillo K.F. Moscow: ROSSPEN Publishers, 2000.

3. In 1912-1914, numerous political and economic problems pushed Germany and Great Britain toward each other and to negotiate the settlement of disputes, however only generating a semblance of dйtente. See Romanova E.V. On the Way to War: the British-German Conflict Evolving. 1898-1914. Moscow: Max Press Publishers. 2008.

4. Special Journal of the Council of Ministers, July 11, 1914 / Special Journals of the Council Ministers of the Russian Empire, 1914. Moscow: ROSSPEN Publishers, 2006. P. 197.

5. Ibid.

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |