The Catalan Labyrinth

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Doctor of History, Professor, Comparative Political Studies Department of the MGIMO University

The Catalan Independence Referendum held on October 1, 2017, and the declaration of independence approved by Catalonia’s Parliament provoked a major political and constitutional crisis in Spain, the worst since the country transitioned to democracy forty years ago. Madrid’s assumption of direct control over the region failed to resolve the crisis and merely moved it to a new phase that is equally dangerous.

Catalan society is split on the issue of independence, and the split cuts right across work teams, families, groups of friends. At the same time, both proponents and some opponents of secession were united in their critical view of the government of the People's Party. They accused it of inaction, of disrespect for Catalans and of lacking specific proposals for resolving the Catalan issue. Catalans who were in favor of holding the referendum wanted it to be legitimate and coordinated with the government.

The upcoming election is highly likely to solidify the split in Catalan society. Some Catalans already view the recent events as a nightmare created by Carles Puigdemont’s actions while others see it as Madrid ocCUPying Barcelona in a manner similar to Franco’s times. Similar polarization may manifest itself at the election. Multiple polls cast the Republican Left of Catalonia party as the winner; the RLC is led by Puigdemont’s former deputy Oriol Junqueras. However, a victory by the RLC does not mean separatists would dominate the Parliament once again, primarily because Puigdemont’s Catalan European Democratic Party, which today is believed to be the leading force in the separatist bloc, will supposedly suffer major losses.

The Catalan Independence Referendum held on October 1, 2017, and the subsequent declaration of independence approved by Catalonia’s Parliament provoked a major political and constitutional crisis in Spain, the worst since the country transitioned to democracy forty years ago. Madrid’s assumption of control over the region failed to resolve the crisis and merely moved it to a new phase that is equally dangerous.

In recent months, the Barcelona–Madrid conflict has been developing at such a breakneck pace that an outside observer would find it difficult to sort through the whirlwind of events that have shaken Spain. Thus, it would make sense to point out the principal landmarks of the conflict in their dialectical totality.

Before the referendum: escalation of the conflict

The Catalan conflict that began brewing at the start of the global crisis entered a new stage in June 2017 when Carles Puigdemont, the head of Catalonia’s Generalitat (government), announced an independence referendum to be held on October 1, 2017. In response, the right-wing conservative People’s Party (PP) represented by Mariano Rajoy stated that the referendum would not be held since it was illegal (according to the constitution, autonomies may not hold referendums without the consent of the central government and a national referendum). As was previously the case, the parties to the conflict demonstrated their utter inability to negotiate. The previously existing constitutional impasse between the Spanish center and the Catalan autonomy was brought back to the light.

The situation was peculiar because the separatists acted within the existing legality and in fact undermined it by using it.

On September 6 and 7, in an attempt to make the referendum and its subsequent actions legitimate, Catalonia’s Parliament adopted two laws. The first, the Law on Referendum, determined the conditions for holding the referendum. Voters would have to answer the question of whether they wanted Catalonia to become an independent state in the form of a republic. Under the law, Catalonia’s independence would be declared by a simple majority vote. A turnout requirement was not set. If separatists gained a majority, independence would have to be declared within 48 hours of announcing the referendum’s results. If the majority responded with a “no” vote, parliamentary elections would be called. In essence, the law created the most favorable terms for independence proponents.

If independence proponents won at the referendum, the second law passed by the Parliament would take effect: “The Law of Juridical Transition and Foundation of the Republic” (also dubbed “The Split Law”). The newspaper El País called it “a mini-constitution” of the virtual Catalan republic. Under the law, Catalonia would become a law-bound democratic and welfare state that respects European and international law. Three languages, Catalan, Spanish and Occitan, would become official and have equal status. Catalonia would assume control over the officialdom and the property of Spain within the Catalan territory, etc. Legal actions against those who promoted Catalonia’s independence and founding a new state would be dropped. Subsequently, elections would be planned to form a parliament that would adopt a new constitution to be approved at a referendum.

Due to their heated confrontation with Spain, the separatists drafted these laws in utter secrecy. In order to adopt them, the parliament altered its approved schedule, which was announced on the day in question at the start of the session. The laws were adopted in an expedited manner. Although standard procedures preceding parliamentary discussions of a draft law take several weeks, an hour and a half were assigned to discussing and amending the draft of the first law, and two hours were assigned to discussing and amending the second law.

The opposition deputies were incensed by the methods the Parliament leaders chose to have these laws adopted and stated that their rights had been infringed upon. Both sessions were tense and turbulent. During the vote, most opposition deputies walked out.

For the separatists, passing these laws marked the creation of a new, parallel legality that parted ways with the legality of Spain. The law on the foundation of the Catalan Republic was classified as the supreme norm that essentially replaced the 1978 Spanish Constitution and Catalonia’s autonomy. The situation was peculiar because the separatists acted within the existing legality and in fact undermined it by using it.

The government responded immediately. The adoption of the two laws that contradicted both the constitution and Catalonia’s autonomy was qualified as a coup d’état and they were suspended. King Philip VI and all of Spain’s state institutions united to defend the law-bound state, the existing constitution and legality. Madrid required the Catalan authorities to account for their expenses to make it impossible to finance the referendum. Fourteen high-ranking Catalan officials were detained. Spain’s Attorney General sent an order to supervisory agencies in major Catalan cities to prosecute mayors who supported the referendum (out of 948 mayors, over 700 favored the referendum, but they governed no more than 40% of Catalonia’s territory). Similar measures were applied to 19 leaders of the Catalan autonomy, in particular, to Carles Puigdemont, head of the Generalitat. The elections committee was dissolved and several voting stations were closed and sealed up. Offices of the Generalitat, enterprises and private houses were searched; ballot boxes and propaganda materials were confiscated.

Courts, the Attorney General, and police played an important role in the struggle to prevent the referendum, while the government was passive. Experts noted that it failed to offer society a clear action program and did not explain what measures (except prohibitive ones) it intended to take. Consequently, many people could not fully understand what was going on, how serious it was, and what could happen next and felt insecure and anxious.

Madrid’s firm stance, detentions and searches prompted mass protests from independence proponents and clashes with law enforcement agencies. Puigdemont accused the state of turning into a repressive regime. A wave of rallies and marches in favor of independence swept Catalonia; several trade unions and civil society organizations spoke out in support of the referendum. Catalans set up referendum protection committees. The referendum’s opponents were insulted and threatened. It went so far that the mayors who disagreed with the Generalitat’s policy were forced to employ bodyguards and make their children stay at home.

Catalonia's split society

Separatist propaganda created an illusion of Catalans largely being in favor of independence.

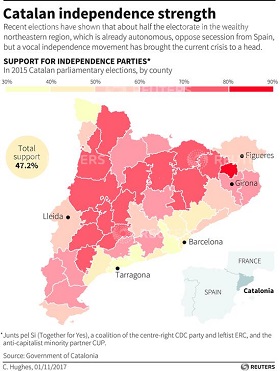

As a result of elections held in September 2015, separatist parties held majority in Catalonia’s parliament. They were represented by the “Together for Yes” (Junts pel Si) coalition that had 62 seats (out of 135). The coalition comprised the right-center Catalan European Democratic Party (PDeCAT) and the leftist Republican Left of Catalonia (RLC). The separatists had the majority due to 10 seats held by the Popular Unity Candidacy (Candidatura d'Unitat Popular, CUP). In ideology and politics, the separatist camp was highly diverse. The right-center PDeCAT and the radical left CUP, with its anti-capitalist, anti-globalist stance were brought together only by the idea of secession. It was CUP, whose 10 seats ensured the separatists their parliamentary majority that played a major part in radicalizing the process.

The proponents of Spain’s territorial integrity included the following parties: the Citizens (Ciudadanos), one of the country's four leading parties, founded in Catalonia in 2006 (25 seats); the Socialists' Party of Catalonia, a branch of Spain’s leading opposition Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (16 seats); Spain’s ruling People’s Party (11 seats); and the Catalonia Yes We Can (Catalunya Si que es Pot) coalition that included the We Can (Podemos) party, which had recently become the third most influential party nationwide. Each union had its own take on resolving Spain’s territorial problems, which made it harder to form an alternative bloc.

Polls held by the Generalitat’s public opinion research center showed that the number of Catalans favoring independence was at an all-time high of 48.5% in November 2013. Since that time, the number of secessionists never exceeded the number of proponents of Spain’s territorial integrity. The latter dominated, but the balance of forces continued to vary from 0.2% (March 2016) to 8.3% (June 2017). In June, three months before the referendum, Catalonia had 41.1% of secession proponents and 49.4% of united Spain proponents. According to the АВС newspaper, since summer 2016, separatists lost 350,000 followers.

The silent majority faced a rather numerous, garrulous, well-organized and well-financed minority.

However, against hard facts, separatist propaganda created an illusion of Catalans largely being in favor of independence. It is easy to explain why the majority, whose voice could often be heard only through polls, generally remained silent. This happened because separatists monopolized many areas of the autonomy’s life, including its public discourse. Back in 1980, the Generalitat headed by Jordi Pujol, the father of today’s Catalan nationalism (he was the head of government for 22 years), set course for “re-Catalonizing Catalonia” and constructing a Catalan identity distinct from the Spanish one; this policy entailed introducing nationalist sentiments into local society by having nationalists seize key positions in the media and education and imposing their views and rules of the game on the region’s society. For example, since the second half of the 1980s, Catalan education has been actively introducing the “language immersion” model intended to steadily push out Spanish and transform Catalonia into a monolingual region. It is worth noting that for years, Catalonia’s “language immersion” system remained the only one of its kind in Europe [1].

Non-nationalist forces failed to oppose the nationalist pressure and offer Catalan society an interpretation of reality that would be equally coherent and convincing for many. Consequently, the silent majority faced a rather numerous, garrulous, well-organized and well-financed minority. Whereas the minority saw a single goal ahead of gaining independence (separatists rarely thought of what would come next), the majority was disjoined by the lack of a single answer to solving the Catalan problem. Using discriminatory practices, the dominant minority succeeded in instilling fear in much of the majority.

The Catalan government regarded the referendum results as a political and moral victory.

Catalan society is split on the independence issue, and the split cuts right across work teams, families and groups of friends. At the same time, both proponents and some of the opponents of secession were united in their critical view of the government of the People's Party’s. They accused it of inaction, disrespect for Catalans and lack of specific proposals for resolving the Catalan issue. Madrid’s recent stance has been said to have transformed many proponents of a unified Spain into “offended nationalists.” 82% of people under age 34 believed that instead of undermining the struggle for secession, Mariano Rajoy’s policies whipped it up. Many of the “offended nationalists” would reportedly leave the separatist camp if a change in the current relations between the autonomy and the Spanish government were to be enshrined in legislation, giving greater recognition to the Catalan identity.

As for the referendum, 70–80% of Catalans have supported it in recent years. At the same time, they did not want the kind of referendum the Generalitat offered; they wanted a referendum that was legitimate and coordinated with the government. Even before October 1, the majority of Catalans polled (56%) believed a unilateral referendum held without coordination with the center would be illegitimate (38% believed the opposite).

Before and after the referendum: the conflict’s metamorphosis

The October 1 referendum was held without democratic guarantees. Since some voting stations had been closed by the police, the Catalan authorities simplified the voting procedure 45 minutes before the start of the referendum. They introduced a single electoral register system that gave every enfranchised person the right to vote at any station regardless of their place of residence. There was no control of the voting. Many Catalans voted in the referendum without submitting proof of identity and could vote as many times as they wanted. Any person not registered in Catalonia could vote, too. One could vote with a ballot downloaded from the Internet and printed out.

Long lines snaked outside voting stations. At many locations, civil guard and national police patrols used truncheons, rubber bullets, and tear gas to keep people away from ballot boxes. Sometimes, rocks were hurled back. The patrols of the Catalan police (Mossos d’Escuadra), which is independent of the national police, behaved differently; they did not prevent voting stations from opening and sometimes protected voters from other police units. The Catalan police was sharply criticized by the authorities for betraying the trust of judges and prosecutors and for “placing political interests above professional duties.” A judicial inquiry was launched against the local chief of police.

According to some reports, 893 voters and 30 police officers sought medical aid after the clashes. The harsh actions by the law enforcement shocked and outraged many people in Spain and abroad, reminding them of the tragic events in Spanish history that had seemingly been left in the past. Such actions bitterly wounded Catalans’ pride and dignity and greatly harmed the already fraught relations between Barcelona and the rest of Spain. The actions of Spanish law enforcement agencies played right into the hands of the Generalitat since it had already traditionally depicted Catalonia as a victim of Madrid’s oppression and willful cruelty; these actions prompted sympathy for separatists among people who, just a short while ago, could not have imagined a life outside Spain. Five days after the referendum, Enric Millo, the Spanish Government’s official representative in Catalonia, apologized for the actions of the civil guard and the national police; his apology, however, failed to diffuse tensions in the region.

The Catalan government regarded the referendum results as a political and moral victory. The Generalitat stated that 90.2% voted for independence and 7.8% voted against it. These results, however, do not reflect the true balance of forces since the voter turnout was only 43%, or 2 million out of 5.3 million enfranchised Catalans. The majority of voters did not turn out for the referendum.

After the referendum, the situation in Catalonia remained exceedingly tense. Throngs of people demanded that the civil guard and the national police mustered from across Spain leave. On October 3, a general strike was held protesting the harsh treatment of voters by the police; the strike had been advocated by over 40 public organizations and trade unions and it paralyzed the autonomy’s normal course of life.

Even though the actions of the Spanish police during the October 1 referendum prompted sympathy for Catalans in many countries, no support was officially expressed, thus dispelling the illusion that Catalonia had the ear of European governments.

On October 10, Carles Puigdemont addressed Catalonia’s parliament; many people had thought his speech would be historical, believing he would declare Catalonia’s independence. However, the address was ambiguous. Initially, Puigdemont signaled that he supported declaring Catalonia’s independence pursuant to the referendum. The audience began to applaud when, a few seconds later, Puigdemont specified that the procedure had been postponed for a few weeks to conduct talks with Madrid. Afterwards, Catalonia’s declaration of independence was adopted. It was signed by Puigdemont, his deputy Junqueras and by 72 deputies, including the speaker Carme Forcadell. However, the declaration did not come into legal force since it had not been put to a vote.

Puigdemont’s ambiguity could be explained by the start of a mass exodus of capital from Catalonia that had hardly been anticipated. At a meeting with Puigdemont, large business representatives called possible the declaration of independence “a bomb under Catalonia’s economy.” In addition, Puigdemont tried to buy time and pinned high hopes on international mediation (primarily by the EU) since he could not negotiate with the Spanish government alone. However, the EU refused to assume the role supported Rajoy’s government, and spoke in favor of Spain’s territorial integrity. Even though the actions of the Spanish police during the October 1 referendum prompted sympathy for Catalans in many countries, no support was officially expressed, thus dispelling the illusion that Catalonia had the ear of European governments.

In this situation, the Spanish government invoked Article 155 of the Constitution. Under this article, if an autonomy fails to comply with its constitutional obligations, the government, after sending a prior notification to the head of the autonomy, may take steps with the consent of the absolute majority of the Senate to force the autonomy to comply with said obligations. It was the first time this article had been invoked during the 40 years of Spanish democracy. Despite serious pressure from members of his own party, among others, Rajoy had long postponed resorting to this article since it meant “entering terra incognita” with unclear consequences. The scope for applying the article could be quite broad, from individual steps limiting the autonomy to its complete abolition.

As a preliminary step before invoking Article 155, the government set Puigdemont an ultimatum: within five days, he had to give an unequivocal answer (yes or no) to the question of whether he had declared Catalonia’s independence in his address (any other answer would be taken as a “yes”). If the answer was “yes,” the Generalitat would be given three more days to remedy the situation and restore constitutional order. If it failed to comply, a list of powers to be stripped from the Generalitat would be forwarded to the Senate in accordance with Article 155. The absolute majority of the People’s Party in the Senate guaranteed that the law would be approved.

Puigdemont’s speech dispelled the illusions of those who had hoped to resolve the Catalan crisis by reaching a compromise solution.

The Spanish government’s ultimatum spurred heated debates among proponents of independence. Puigdemont was subjected to powerful pressure from all sides. Radical separatists, disappointed by his ambiguous address to parliament, demanded a more unequivocal declaration of independence. Moderates were not, in principle, averse to negotiating with the Spanish government. Ultimately, once the five days expired, Puigdemont had failed to clarify Catalonia’s status after the secession referendum; simultaneously, he called upon Madrid to engage in a dialogue.

In Madrid’s interpretation, a lack of an unequivocal answer meant that Puigdemont supported Catalonia’s independence. On October 21, the Spanish government made the decision to invoke Article 155 of the Constitution and sent the Senate a proposal to remove Puigdemont and the entire Catalan government from office. Madrid assumed control of Catalonia’s police, revenue and expenditures, telecommunications, e-communications, and audiovisual means. Rajoy called elections to the regional parliament to be held within six months. Spain’s government described this step as harsh, yet commensurate with the Generalitat’s grave actions.

The government’s stance was supported by the leading opposition parties: the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party and the Citizens. This support is of crucial importance. When Puigdemont embarked on his risky venture, he must have counted on the weakness of the government of the People’s Party, which did not have a parliamentary majority and opposed the socialists on many issues. Yet in a time of hardship for the country, the SSWP leaders supported the government. The We Can party took a dissenting stance: it was against invoking Article 155 of the Constitution since it considered it an infringement upon democratic freedoms, and it also supported holding a referendum coordinated with the Spanish government.

Instead of being stark and triumphant, the separatists’ victory was dull and inexpressive.

Puigdemont was faced with a dilemma: either declare independence or call a snap election, a course of action that was insisted upon by proponents of a compromise solution to the problem. The first option meant a head-on confrontation with Madrid and the invocation of Article 155 by the Senate. The second option meant the government would withdraw the article from the Senate and freeze its invocation. At the same time, calling a snap election would also mean that Puigdemont had refused to capitalize on the fruits of the victory in the October 1 referendum and declare independence. His followers would see it as treason and surrender.

Puigdemont was clearly hesitant. On October 26, his speech with an answer to the Spanish government was postponed twice. As Puigdemont realized the impracticability of this endeavor, he was claimed to be ruled by “two fears”: a fear of becoming a traitor in the eyes of his followers and a fear of finding himself in jail. The press ran reports of him intending to dissolve the parliament and hold a snap election in December. Ultimately, another decision was made. The head of the Generalitat said there would be no election since there were no sufficient guarantees that it would be held properly. He assigned the responsibility of declaring Catalonia’s independence to parliament. Puigdemont’s speech dispelled the illusions of those who had hoped to resolve the Catalan crisis by reaching a compromise solution.

Article 155 in effect: a new phase of the crisis

On October 27, Catalonia’s parliament voted for the resolution to declare the region’s independence from Spain. Catalonia was declared an independent sovereign republic. The vote was held by secret ballot. Seventy MPs voted in favor (out of 135), 10 voted against, and two abstained. Opposition MPs from the PP, the SSWP and the Citizens left the session and thus boycotted the vote. Instead of being stark and triumphant, the separatists’ victory was dull and inexpressive. They gained a mere two votes above the simple majority they needed to win.

In response, the Senate approved invoking Article 155 of the Constitution in regard to Catalonia. At an emergency government session held later, Rajoy announced that, in accordance with Article 155, he was removing the Catalan government from office, dissolving the regional parliament (the question of dissolving the parliament had not been considered prior to the declaration of independence) and holding new elections on December 21, 2017 (much earlier than planned). Direct rule from Madrid was put in place. It was also announced that the resolution declaring Catalonia’s independence would be challenged in the Constitutional Court. Later, the Attorney General charged Puigdemont and other leaders of the separatist bloc with rebellion in connection with the declaration of independence. They could face long prison terms.

Puigdemont did not recognize the decision of the Spanish authorities and called upon his followers to resist democratically. It remains unclear, however, how forceful this resistance will be. In the first days after declaring independence, leaders of the separatist bloc behaved in a way that showed that they had resigned themselves to the invocation of Article 155. Puigdemont himself departed for Brussels with five of his aides (some Spanish media view it as fleeing Catalonia); his further plans are not known. The separatists are confused. The following confession of an average fighter for independence is typical, “I don’t know what we have now, a [declared] republic or Article 155 of the Constitution.” Those most active in the separatist camp today are journalists and scholars who believe that the invocation of Article 155 and a speedy snap election testify to Spain’s weakness and Madrid’s inability to govern Barcelona democratically; consequently, they view these factors as their moral victory.

Now, “under Madrid’s wing,” opponents of independence certainly feel far more confident.

The latest events demonstrated that the separatist bloc suffered some local, yet grave defeats. First, it was not supported by a significant part of Catalonia’s medium and large businesses. As of October 30, 1,821 enterprises had changed their registration addresses and left the region. Second, separatists turned out to not have control of the “streets.” Back on October 8, Barcelona held a powerful rally attended by thousands of people; the rally’s slogan was “Enough, let’s recover our common sense.” They took to the streets again on October 29, two days after the separatists declared independence. The police say 300,000 people took part in the rally; the organizers put the number at 1 million. Now, “under Madrid’s wing,” opponents of independence certainly feel far more confident. Third, after Catalonia declared independence, EU politicians issued new statements denying support to separatists.

By scheduling the Catalan snap election for December, Madrid made a precise and well-calculated move. First, the “emergency” period in the potentially dangerous region is reduced to a minimum. In addition, the government’s proposal forced separatists to make a choice and deepened frictions between them on whether to boycott the election or take part in it. Boycotting the election would mean continuing to act within a parallel legality, while taking part in it would mean sacrificing their principles and returning to Spain’s legal framework (recent months have shown, though, that separatist parties could operate within two legalities simultaneously). The Catalan European Democratic Party and the Republican Left of Catalonia said they would take part in the election; the Popular Unity Candidacy, on the contrary, has refused.

The upcoming election is highly likely to solidify the split in Catalan society.

The upcoming election is highly likely to solidify the split in Catalan society. Already now, some Catalans view the recent events as a nightmare created by Carles Puigdemont’s actions while others see it as Madrid occupying Barcelona in a manner similar to Franco’s times. Similar polarization may be seen at the election. Multiple polls cast the Republican Left of Catalonia party as the winner; the RLC is led by Puigdemont’s former deputy Oriol Junqueras. However, a victory by the RLC does not mean separatists would dominate the Parliament once again, primarily because Puigdemont’s Catalan European Democratic Party, which today is believed to be the leading force in the separatist bloc, will supposedly suffer major losses.

At the other flank, polls predict major success for the Citizens party with its Catalan roots and consistent stance against separatism (it proposed invoking Article 155 much earlier than Rajoy did). At the same time, the possibility of pooling forces to triumph over their rivals is being discussed in both camps. However, the situation in Catalonia is changing at such a breakneck pace that today’s forecasts and scenarios may radically change tomorrow.

Apparently, elections may normalize the situation, but they cannot truly defuse the Catalan problem. Using prohibitive measures alone, as it was done previously, is ineffective and inexpedient in the long run. When the Catalan crisis broke out, the elites in power were forced to re-think their previous, outdated approaches to the country’s territorial and political structure. Will they indeed do it?

1. Cataluña. El mito de la secesión. Desmontando las falacias del soberanismo. Madrid, 2014, p. 221

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |