The Battle of Kursk: a Geopolitical Victory

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

Former First Deputy Chief of the Military Science Department, Russian Armed Forces General Staff

The Kursk Bulge was the arena of the most violent and decisive battles of the Second World War, the arena for the Soviet people to demonstrate bravery and mass heroism and determine the outcome of the battle against fascism.

The 70th anniversary of the Battle of Kursk

The road to victory in the Great Patriotic War was incredibly rough and blood-spattered for the Soviet people, who struggled forward despite defeats and retreats, enormous losses, hardships and destitution. But not only did they stop the enemy but also reversed the tide of the war and overwhelmed the main forces of the fascist bloc. Strategic decisions by the Soviet leadership, logistic support for the frontline, and spiritual unity on the home front and the battlefield laid the groundwork for an irreversible turnaround, the geopolitical victory of the Soviet people and the world community.

The Kursk Bulge was the arena of the most violent and decisive battles of the Second World War, the arena for the Soviet people to demonstrate bravery and mass heroism and determine the outcome of the battle against fascism.

Strategic Plans of the Sides

The Soviet offensive during the winter of 1942-1943 and forced retreat during the Kharkov defensive operation of 1943 formed the so-called Kursk Bulge.

Soviet forces from the Central and Voronezh Fronts deployed there threatened the flanks and the rears of German Army Groups Center and South.

At the same time, these German formations at the Orel and Belgorod-Kharkov footholds were able to launch powerful flanking attacks against Soviet troops defending the Kursk area. In order to take advantage of the opportunity, German leaders began preparations for a major summertime offensive in this direction.

The planners of Operation Citadel intended to employ converging attacks from the south and north against the bottom of the Kursk Bulge in order to encircle and destroy the Soviet forces on the fourth day of battle.

Thus, the German command expected to deliver a series of forceful strikes, crush the Red Army’s main body in the central portion of the Soviet-German front, retake the strategic initiative and turn the situation to their favor.

Operation Citadel employed the best Wehrmacht generals and most efficient contingents – all in all, 50 divisions (including 16 tank and motorized divisions) and numerous separate units within the 9th and 2nd Armies of Army Group Center (Field Marshal Günter von Kluge), the 4th Army and Army Detachment Kempf of Army Group South (Field Marshal Erich von Manstein). These were supported by the 4th and 6th Air Fleets. The entire grouping included over 900,000 men, about 10,000 artillery pieces and mortars, almost 2,700 tanks and self-propelled assault guns, and approximately 2,050 aircraft.

In its turn, the Soviet General Headquarters’ 1943 summer-autumn plans provided for a broad offensive with a main strike in the southwest to destroy Army Group South, liberate the Left-Bank Ukraine and Donbass, and cross the River Dnepr. Designing the new campaign, the General Headquarters envisaged both variants but selected the most rational plan upon receipt of intelligence on the enemy’s preparations for the Kursk offensive. The Soviet command chose the strategic defense at the Kursk Bulge in order to exhaust the key enemy grouping, counterattack and then defeat the Germans in that area.

Combined strategic defensive (July 5-23, 1943) and offensive (July 12-23, 1943) operations in the Great Patriotic War executed by the Red Army in the Kursk Bulge area with the aim of frustrating a major German offensive and crushing the enemy’s strategic grouping are historically titled the Battle of Kursk [1].

The Battle of Kursk, Unmatched in World History

The Kursk defensive operation unfolded along the 550-km frontline and brought a complete breakdown to the Nazi Operation Citadel. The operation engaged troops from the Central and Voronezh Fronts, as of July 1, 1943 numbering 1,337,165 servicemen, 21,686 artillery pieces and mortars (less 50-mm mortars), 518 rocket artillery units (BM-8 and BM-13), 3,489 tanks and self-propelled artillery vehicles, and 1,915 aircraft. Repelling the offensive, the Soviet forces set the ground for a counterattack.

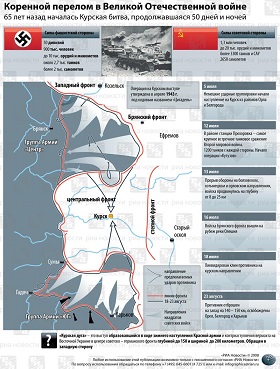

The unprecedented in scale 50-day-long Battle of Kursk – from July 5 to August 23, 1943 – was the pivot point of the Second World War.

The fighting was unparalleled in its violence, persistence and concentration of forces, primarily armor and aircraft, within a limited time and geographic area, as well as by the drive of the sides to attain victory at any cost.

On July 12, the Soviet troops embarked on the offensive at the Kursk Bulge. That day railway station Prokhorovka, 56 km north of Belgorod, witnessed the largest tank battle of the Second World War with the participation of 1,200 tanks and self-propelled guns. The battle lasted all day long and resulted in the Germans' retreat with losses of about 10,000 men and over 360 tanks. By August 23, the enemy was flung back 150 km to the west, with the cities of Orel, Belgorod and Kharkov liberated.

After the Kursk victory, the odds were in the Soviet favor. The Red Army blocked the enemy and delivered a crushing blow. But the price was high, as military historians still cannot assess the losses in terms of manpower and material, only agreeing that they were colossal on both sides.

The Battle of Kursk became the geostrategic pinnacle of crisis-style tensions and the turning point of both the Great Patriotic War and the Second World War.

The Price of Victory: the Frontline and Home Front United

The Soviet troops and their support area in the Kursk Bulge area faced a hostile environment of winter snowfall and springtime slush. Task forces, formations and units had to move from railway stations on foot, with no supply bases of their own.

Having lost many weapons and material in the border clashes and in battle in 1941-1942, the country had to strain every nerve and set industry going in order to make up for the losses expediently and accumulate reserves for crushing the aggressor.

By the beginning of the counteroffensive, the fronts were sufficiently provided with ammunition, as just in June 1943, they received 4,781 boxcars, with 1,587 going to the Central Front, 2,237 to the Voronezh Front, and 957 to the Bryansk Front.

The Red Army suffered enormous human and

materiel losses, with 8,881 wounded men

serviced by medics of the 1st Tank Army in

July 6-15

Apart from the change in the direction of the military struggle, the Soviet economy was performing much better and was able to provide for the organizational restructuring of the Red Army’s logistic system [2].

As a result, there were no ammunition shortages both during preparations and in the battle. Ammunition expenditures were unheard of for such a short period of time, but the stock was about standard even by the battle end.

During the defensive battle, the Central Front expended 1,632 boxcars of ammunition, and the Voronezh Front – 960 boxcars. The counterattack expenditures were as follows: Central Front – 1,619, Bryansk Front – 1,842, Voronezh Front – 825, and Steppe Front – 295 boxcars (with the total at 7,173 boxcars from July 5 to August 24).

During eight days, the Central Front spent 387,000 antitank cartridges, i.e. 48,500 per day. The Voronezh Front used 754,000 cartridges, i.e. 68,500 a day, in 11 days of defensive operations. In the entire defense period, both fronts devoured 665 boxcars of mortar shells of all calibers, 1,220 boxcars of artillery and antiaircraft shells, and 280 boxcars of small arms ammo.

The Red Army suffered enormous human and materiel losses, with 8,881 wounded men serviced by medics of the 1st Tank Army in July 6-15.

Certain foreign economists insist that the victory would have never come in absence of the Lend-Lease program. However, in the second half of the war, the Soviet Union was financing the defense with 324.1 million rubles daily, with 1943 expenses reaching 125 billion rubles, and during the entire Great Patriotic War – a total of 485 billion dollars, while the Lend-Lease total made up only 10.8 billion dollars [3].

Possessing three times less metal and four times less coal than Germany, the USSR reached average annual production above the German level, with two times as many aircraft, almost two times more tanks, four times more artillery pieces, and almost 1.5 times more bombs and mortar shells.

During the war, the USSR manufactured 489,900 artillery pieces, 102,500 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 136,800 aircraft. For comparison, the U.S. and British supplies amounted to 9,600 artillery pieces, 11,576 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 18,753 aircraft. Speaking in Congress on May 20, 1944, U.S. President Roosevelt mentioned that the Soviet Union was using domestically built weapons.

Geopolitical Significance of the Kursk Battle

Polish 1st Infantry Division, formed in Russia,

leaves for the front in summer 1943

After the Battle of Kursk, the tide of the Second World War utterly reversed toward the victory of the anti-Hitler forces and the inevitable defeat of the fascist bloc.

The battle of Kiev saw the bravery of the 1st Czechoslovak Brigade under the command of Ludvik Svoboda, while northeast of Mogilev, in battles for Lenino within the Western Front, the Polish 1st Kościuszko Division took to the war path.

In the second half of 1943 and early 1944, over 350,000 guerillas were operating in the territories occupied by Germans, with vast lands liberated and under guerilla control.

The military successes of the USSR strengthened the country’s international prestige, with nine more states establishing diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in 1942-1943. At the same time, Germany’s stance was on the downward spiral stimulating the dissipation of the fascist bloc.

From October 19-30, 1943, Moscow hosted the conference of the three great powers at the level of foreign ministers, which adopted a resolution on waging the war until the complete and unconditional surrender of Germany and on principles of the post-war settlement.

The Soviet-Anglo-American coalition was significantly boosted by the Tehran Conference (November 28 – December 1, 1943) that adopted a declaration on the common course of the three powers toward the war and post-war cooperation.

In Tehran, Western allies pledged to intrude in northern and southern France, opening the second front in Europe before May 1, 1944.

Thus, Berlin’s hopes for a split in the anti-Hitler coalition failed, and the victorious completion of the Great Patriotic War and the Second World War began.

In this regard, Western allies finally decided to open the second front, and on June 6, 1944, British and American troops landed in Normandy, northern France (Operation Overlord) to launch strategic interaction between the Soviet and Anglo-American forces.

Development of the State’s Military Organization Requires a Contract with Private Sector

The introduction of market-oriented relations and reform of the Russian Armed Forces require a clear-cut economically-founded government program for the development of the military organization. Changes to the Army, Navy and other state structures do not seem viable in the absence of a healthy economic foundation. Otherwise, the process heads nowhere, with its drivers blindfolded.

Reforms also have another side, since each time reformers should look back to trace the starting place of the processes.

The Battle of Kursk indicates that the outcome would not have been that tragic if the logistic high command had possessed an appropriate modular reserve of material (and there were appropriate opportunities) to replenish damaged arms and expenditures.

We believe that the Russian Armed Forces should be provided with standard interchangeable modular rear formations with material reserves for both local and large-scale wars.

Modular logistic support is widely used by foreign militaries and is sure to suit the task forces, commands, units and establishments of the Russian Army and Navy. International practice shows that during the post-war period the strength of division support in the U.S. Army took up 26-28 percent of the division, with a 30-32 percent share in the West German Army. As for NATO forces in Western Europe, each second serviceman is somehow attached to logistic, medical and other support systems [4].

In future wars, the trend to bring logistical facilities closer to troops engaged in action is sure to intensify, as was the case in Afghanistan and Chechnya. Support commands, units and detachments must be provided with appropriate defenses and protection to increase the survival rate of the support facilities and the stability of the support process.

Research shows that consumption of material per serviceman is rising from war to war – from six to twenty kilos in the First and Second World Wars. Should a nuclear war break out in the future, the estimate would exceed 200 kilos.

An analysis of logistic support patterns in Tsarist Russia, in the Soviet Union and in several foreign countries indicates that government supplies prevail even in high-level market economies. In modern Russia, the shallow perception of the market economy as a self-regulating system functioning without government participation gives room to a pragmatic and balanced approach to solution of problems on the basis of better government regulation for deliveries of weapons, equipment and materiel to the Armed Forces.

Fro example, the U.S. Department of Defense performs its economic activities exclusively on a contract basis, as the buyer of weapons, equipment, raw materials, materiel and services. The U.S. Government contract is a sophisticated and universal economic instrument effectively containing basic laws in a concentrated form. The contract regulates all activities of the supplier, defines the government’s obligations, and incorporates legal, social, financial, economic, industrial and other terms of the contract execution. The country numbers over four thousand legal acts on supplies of goods and services to the armed forces. All Western state enterprises and other military suppliers are entitled to subsidies. In the U.S.A., they make up 33 percent, in Sweden over 51 percent, in France 46 percent, and Great Britain 45 percent.

Russia should work hard to find a system of its own that would meet its economic, political, historical, military, geographic and many other needs. In a market economy, the Army and the Navy should seemingly obtain goods on a contractual basis both in peacetime and wartime, while the state must adopt appropriate federal laws to guarantee deliveries and services [4].

The Kursk Tank Battle of the Future

Ukrainian modern Tank T 84 OPLOT, Kharkiv

Morozov Machine Building Design Bureau.

They designed T-34, the best tank of the WWII.

In the near future, such a tank battle seems unlikely, since wars to come will be smaller in scale and characterized by local and focal features, as well as by indirect action strategies.

But who has said that tanks are irrelevant? Who has said we shall employ present-day tanks? Who knows how many and what kind of tanks we shall need? Shall we create Tank-100 or upgrade those in use?

So many questions – so many answers, and both require profound professional analysis.

Notably, foreign countries also attempted to modernize Soviet tanks. The Israelis took the lead, as they used T-54s and T-55s captured from the Arabs to replace the 100-mm guns with British 105-mm guns, and the 7.62-mm machineguns with Browning pieces. They also installed more powerful American radios and had the upgraded tanks designated T1-67.

In mid-1980, Iraqis modernized their T-62 and T-72 tanks by improving the armor with sheet-type explosive plates.

Thus, back in the 1960s, local wars and armed conflicts witnessed maneuverable medium-size tanks that were properly armored and able to powerfully fire on the move.

During the past 35 years, tanks' battle efficiency has grown three or four-fold to make them suitable for missions within tank units and tactical battle groups, which is especially significant for local wars and armed conflicts.

Nevertheless, the key criterion for the ability of troops/forces to handle a military conflict is still the quantitative/qualitative balance of opposing forces. This criterion is used to determine the required balance of assets needed to militarily contain and prevent an aggression, or localize and resolve a military conflict with swift and decisive military action.

The minimum balanced composition of force groupings created for the resolution of military conflicts should match the required levels of defense sufficiency determined by the degree of military threat. A balanced composition means a minimum composition of formations equivalent in combat capacity to the opposing enemy grouping. Such groups are not always symmetrical as their assets will complement the combat potential of task forces, with the overall balance reached even in case of total asymmetry of the confrontation.

The establishment of groupings required for conflict resolution should invariably account for their military-economic characteristics.

In the future, Russia's military strategy will be significantly influenced by the military and political environment, including the possible structure of European military security and the collective security of the CIS.

Even now, the point gives rise to many complex questions.

How should the military security system be built? What is its possible purpose? What kind of components should be incorporated? What should be its internal and external structure? How about organization and mechanism for its operation in peacetime and wartime, let alone Incorporation of national defense structures and collective CIS security into the overall system of European and Asian security?

Of course, intermediate variants should not be neglected. For example, the formation of separate elements of military security within the upgraded Partnership for Peace program, the dissolution of the CIS or, vice versa, strengthening of its integration ties.

A critical assessment of each model suggests an account of various military and political conditions that may emerge in the early third millennium and later, which means that a single-valued prediction for Europe and Asia in 10, 20 and all the more 50 years appears unconvincing.

1. History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union 1941–1945. Volume 6, Moscow, 1960–1965; Logistic System of the Soviet Army in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945, Volume 3, Leningrad, 1963; Financial Service of the USSR Armed Forces in the Wartime. Moscow, 1967; The Logistic System of the Soviet Army. Moscow, 1968; The Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union 1941–1945: a Brief History. Moscow, 1970; History of the Second World War 1939–1945. Volume 12, Moscow, 1973–1982; The Logistic System of Soviet Armed Forces in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945, Moscow, 1977; The Great Patriotic War 1941–1945: Encyclopedia. Moscow, 1985; History of the Russian Logistic System (XVIII–XX Centuries). Book 4, St. Petersburg, 2000; The Logistic System of the Armed Forces: 300 Years [Military History Album]. Moscow, 2000.

2. N.A. Voznesensky. Military Economy of the USSR during the Great Patriotic War. Moscow, 1948; A.V.Khrulev. Establishment of Strategic Logistics during the Great Patriotic War // Journal of Military History. 1961. № 6; V.K.Vysotsky, A.S.Taralov, K.P.Tereyokhin. Logistics of the Soviet Army during 40 Years. Leningrad, 1958; A.S.Kustikov, M.Belfer. Tactical Logistics during the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945. Leningrad, 1974; A.I.Marchenko, M.S.Semyonov. Food Supplies to the Forces during the Great Patriotic War // Works of the Military Academy for Logistics and Transportation. Leningrad, 1965; A.S.Domank. Logistics of the Fiery Bulge. Voronezh, 1989; V.M.Moscovchenko, et.al. Logistics of the North Caucasian Military District. Rostov-on-Don, 1998; I.M.Zorin. Procurement of Foods and Forage at Locations as a Source for the Red Army Supplies during the Great Patriotic War: Candidate of Military Science Dissertation. Kalinin, 1945; P.I.Chesnokov. Organization of Food Supplies for the Active Army during the Great Patriotic War: Candidate of Military Science Dissertation. Kalinin, 1952; L.P.Morozov. Problems of Logistic Support in Preparations and during the First Defensive Operation in the War Early Period on the Continental Theater: Candidate of Military Science Dissertation. Leningrad, 1992; Medical Support of the Don Front in the Stalingrad Operation: Candidate of Military Science Dissertation. Leningrad, 1947.

3. G.K.Zhukov. Reminiscences and Deliberations. Moscow, 1974; A.M.Vassilevsky. The Cause of my Entire Life. Moscow, 1973; K.K.Rokossovsky. Soldier's Duty. Moscow, 1997; I.S.Konev. Memoirs of the Front Commander. Moscow, 1991; N.N.Voronov. On the Military Service. Moscow, 1962; A.G.Zverev. Memoirs of a Minister. Moscow, 1973; N.A.Antipenko. At the Main Direction. Memoirs of the Deputy Front Commander. Moscow, 1971; D.V.Pavlov. Courage. Moscow, 1983; F.S.Saushin. Our Soldiers' Bread. Moscow, 1980; V.N.Dutov. Memoirs of a Military Financial Officer. Moscow, 1994.

4. A.I.Mirenkov. Thus We Won // Army Collection. 2000. № 6; Logistics in the Battle of Stalingrad // Learning the Military History. A collection of articles of the Institute of Military History, Ministry of Defense, Russia. Issue 6, Moscow, 2000; A.I.Mirenkov. The Sword that Crushed Hitler's Citadel // Journal of Military History, 2000. № 6.

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |