Discipline and Punish Again?

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of History, Professor of the Comparative Political Studies Department at MGIMO-University, RIAC expert

Ph.D. in Political Science, Leading Research Fellow, Head of the Center for Italian Studies, Institute of Europe of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Associate Professor at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, RIAC Expert

In the recent years, a trend towards a narrowing of the sphere of individual freedoms has been observed throughout the world. At the same time, we see the expansion of sovereign freedoms — the sphere where government allows itself to interfere with a citizen's private life. Instead of liberal, creative and unfettered individuals we may obtain a sort of "ant colony state" — a community of inert, disengaged and totally controlled masses.

Another Edition of Police State or Back to the Middle Ages

In the recent years, a trend towards a narrowing of the sphere of individual freedoms has been observed throughout the world. At the same time, we see the expansion of sovereign freedoms — the sphere where government allows itself to interfere with a citizen's private life. Despite a widely declared commitment to the liberal values and multiple attempts of Western countries to force "authoritarian" rulers to respect human rights using various types of sanctions, the modern liberal state has so far failed in clearing itself of charges of regular violations of human rights and double standards. The problem is that rationality as a key liberal principle may be directed not only towards freedom and progress but also towards control for the sake of progress and, in the worst case, control for the sake of control. As a result, instead of liberal, creative and unfettered individuals we may obtain a sort of "ant colony state" — a community of inert, disengaged and totally controlled masses.

Freedom to Be Disciplined

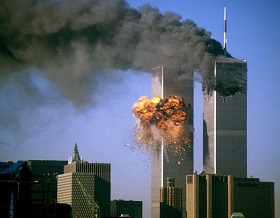

The most active discussion of this trend began after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 when the US Government declared a "war on terror" and adopted the "USA Patriot Act", severely limiting citizens' rights. This document not only increased significantly the ability of security services to wiretap phone calls, to conduct body search of passengers at airports and to take other, seemingly natural in this situation, measures but also allowed for monitoring of private cash flows and reducing significantly the effect of banking secrecy — in order to prevent terrorist financing [1]. The Act expired on 1 June 2015, however, the new law introduced by the Barack Obama Administration ("USA Freedom Act"), although somewhat complicating the activities of security agencies, will enable the government to spy on citizens.

However, in the big scheme of things, the USA Patriot Act was only the tip of the iceberg: its underwater part had formed for many decades, starting as early as the time of the rise of liberalism. The Age of Enlightenment, namely the enlightened thinkers of the 18th century and liberalists of the 19th century, had generated the idea of a minimal state, which later, in the texts of Anglo-Saxon political philosophers of the 20th century, transformed into the concept of a "night-watchman" state aimed to protect human rights and entitled to interfere with a citizen's private life but only to the extent necessary to ensure his safety.

of the Prison

Nevertheless, the transition from the medieval perception of the position of a human being, his relationship with the government and methods of punishment to liberalism was accompanied, as was clearly shown by Michel Foucault, by a growing tendency towards the disciplining, which, naturally, suggested (as opposed to liberal views) a constantly increasing invasion of an individual's privacy. The boundary, which, in theory, a "night watchman" should not cross, again moved towards a restriction of individual freedom and an increased control of an individual's behaviour. Ambiguous zones were formed again, in which a human being found itself extremely vulnerable in the face of the government machine and the unpredictability of practices of physical and structural violence applied to him.

Even as late as the 20th and 21st centuries, despite liberal thinkers' declaration of freedom of an individual from government interference, this interference continued and increased in new forms — not in the form of tortures or brutal executions (as in the Middle Ages) but in the form of a constantly increasing government surveillance of each individual's behaviour. Since approximately the 1920s, a rapid development of the so-called "controlling" and "disciplining" power has been observed. Today, even in the institutionalised democracies there are non-institutional (non-system) policy instruments, which often simply negate the democratic institutes existing on paper and allow an individual's private space to be invaded both in emergency situations and in day-to-day regime of restrictions and control.

It is fair to say, though, that the strengthening of control was justified by the well-being of the individual or citizen himself. Yes, clinical medicine made the "body" an object of power but it has led to a sharp improvement in quality of life. Yes, the law enforcement apparatus deeply penetrated in society but, in a whole number of cases, it has resulted in lower crime rates. Yes, electronic communication means make an individual almost fully "supervised" but data transfer speeds have increased many-fold. One can put forward many similar arguments. The question is, which limit the growth of control should reach to negate the benefits it brings to an individual. At a certain stage, control becomes a goal in itself and its relation with the increase of benefits becomes at least not obvious.

"Big Brother" Is Watching You

Several tendencies of the 20th and early 21st century evidence that the practice of reducing individual freedoms and increasing government interference with an individual's private life is not decreasing but, to the contrary, is expanding. Let us consider the most noticeable among these tendencies in detail.

1. Imposing restrictions on freedom of movement and introducing practices to control the movement of individuals became one of these tendencies. It was evidenced by the introduction of a visa regime, which would seem unthinkable for Europeans of the 18th or 19th centuries. At the end of World War I, visas started being actively used as a tool to restrict the migration, to ensure safety and to identify agents of foreign countries. Since the 1930s, the USSR had started introducing visas to leave the country. Such "exit" visas were aimed to stop the most pro-opposition citizens from leaving the country and use repressions against them within the country. Similar regimes can still be observed in countries with the toughest authoritarian regimes (for example, North Korea; certain forms of exit visas still exist in Uzbekistan, Saudi Arabia and Qatar), which are actively criticised by the UN.

The introduction of passports and further strengthening and improvement of control of the passport system (which has now reached its perfection due to embedding chips containing personal information in passports) is attributed to the same category of measures to control the movement of individuals. The very idea of biometric documents originated in the United States following the events of 11 September 2001. In 2002, the representatives of 188 countries signed the New Orleans treaty that recognized the biometrics as a core technology of identification of the next generation passports and entry visas.

2. Special mention should be made of the practice to track private funds on bank accounts, meaning practically the end of banking secrecy, which took place in the first decade of the 21st century, and constituting a very serious restriction on individual freedoms, diametrically opposite to the "free capitalism" model. However, banking secrecy was one of the key elements of this model. In Switzerland, for example, where bank secrecy created by the Swiss Banking Act of 1934 was one of the pillars of the financial system and one of the reasons for prosperity of the banking sector, it became questionable. On 17 June 2010, the Swiss Parliament ratified an agreement between the Swiss and the United States governments allowing UBS bank to transmit to the US authorities information concerning 4,450 American clients of UBS suspected of tax evasion. In addition, on 1 February 2013 a new Swiss federal law on international assistance in tax matters entered into force, which establishes the procedure for responding by Swiss tax authorities to requests of foreign countries. Although Switzerland has not yet talked about the liquidation of bank secrecy, the very possibility and practice of obtaining information about bank clients' accounts is increasingly taking shape.

3. Measures to restrict individual freedoms for government needs also include indefinite detention and preventive custody. Such measures have been applied quite widely throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, both in legal form and in the form of non-regulated practice. Thus, for example, in 1994, indefinite detention was introduced to Australia for Vietnamese, Chinese and Cambodian refugees. In 2004, the High Court of Australia ruled that the indefinite detention of a stateless person was lawful. The same applied to rapists and sex offenders. In Malaysia, the Internal Security Act, adopted in 1960 and remained in effect until 2012, allowed for indefinite detention without trial for 2 years and longer [2]. The Internal Security Act of Singapore enables the government to arrest and detain indefinitely a person who is a threat to national security. In Germany, where until 1998 the maximum duration of preventive detention had been 10 years, the ruling coalition of the Social Democrats and the Green Party abolished these restrictions in 1998. Thus, the government obtained the opportunity to extend the periods of preventive detention for presumably dangerous delinquents. However, perhaps, the most infamous example of indefinite preventive detention without trial was the notorious American prison Guantanamo, a detention camp for detainees accused by the US Government of terrorism and war crimes. In 2002-2006, over 750 foreigners captured by American troops during operations in the territories of Afghanistan and Iraq were detained there. As of April 2006, 490 prisoners remained in the camp, out of which only ten were officially charged. Most of them were citizens of Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan and Yemen. In 2009, Barack Obama declared his intention to reform the prison and to shut down the camp, however, the President's decision was not implemented and the prison continues to function.

4. The practices of snooping, wiretapping and other methods of invasion of privacy, including in respect of government officials, have become so widespread that regularly provoke international scandals. After the well-known Watergate scandal resulted in Richard Nixon's resignation from the office of President, this practice not only did not ceased but continues to gain momentum. The immensity of the disaster has become known to a wider public owing to the activities of Julian Assange and Edward Snowden. Phone conversations between top public officials are wiretapped even between ally countries (it will suffice to recall a scandal between France and the US in June 2015). In this regard, the modern world is indeed not far from the Middle Ages, adjusted, however, by the sharply increased technical capabilities.

5. The practices of humanitarian interventions and other operations justified by the necessity to combat terrorism and regimes violating human rights constitute a remarkable example of unauthorised invasion of privacy by current governments. The NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, military invasions in Iraq without the UN Security Council authorisation, operation in Lebanon, etc. are sad examples of situations where thousands of people are killed in the name of an obligation to protect. Protection of human rights of some people turns out death of others. In this case, a wide discussion is necessary to determine the borders of sovereignty of the state, citizens and third countries; however, it is not the subject matter of this paper. One thing is obvious, though — in the modern world, there are still some, and even more, threats to the personal sovereignty, and military invasions (be it humanitarian interventions, operations aimed at fulfillment an "obligation to protect", operations under the slogans of combating terrorism, etc.) pose the biggest threat to human rights, even to the right to life.

Thus, the practice of European and especially North American governments in respect of development and application of new means of control of individual behaviour starts to copy the practice of the totalitarian regimes in Europe in the 1930s. This trend was vividly described by Giorgio Agamben in his most famous works [3]. In particular, G. Agamben names a few of such "ambiguous zones" ("zones of exclusion") in the modern state, where an individual is deprived of all rights except the right to biological existence ("bare life"): concentration camps, prisons, immigration detention centres, customs, etc. G. Agamben, therefore, managed to demonstrate that sovereign power can expand through the narrowing of the sphere of individual sovereignty, even bringing the subjectivity of an individual to the biological existence.

Although we would like to hope that such phenomena as concentration camps remained in the past, the practices of preventive custody or indefinite detention without or before trial still take place. The existence of such zones constitutes the empirically determined limit of liberalism of modern state.

In practice, invasion of privacy occurs at all levels, from unreasonably high fines for violation of the rules while driving a car to strict control of personal spending. The communication revolution only strengthens this control. Now, it is possible to track constantly the tiniest details of an individual's activities in a real-time mode, from location to physical parameters. All these measures are normally justified by security considerations [4] and legalised by documents such as the Patriot Act. Thus, a French equivalent of the Patriot Act appeared in May 2015 [5], providing the French security agencies with wide opportunities of spying on individuals and more active use of technical means that have previously been used only with authorisation of judicial authorities. In April, a similar act was adopted in Canada [6].

Total Securitisation: Why and What for?

Universal securitisation takes place, types of security multiplying — energy security, food security, transport security, and so on and so forth. Some political experts even mention "securitisation of policy" in this regard.

A principal question arises — to which extent is this global securitisation justified? To which extent does it actually result in the real increase in the public safety? When studying this question, we see that there is no decisive answer to it. A number of phenomena observed in the modern world, in particular, globalisation, results in widespread movement of masses of people. Taking into account that migrating individuals belong to different cultures, originate from countries with different government and political structure, have different levels of education, the "total securitisation" seems sufficiently justified, even by looking at flows of immigrants from Africa to Europe (among whom there are, obviously, quite a few followers of radical Islamic teachings and mere outcasts). However, as demonstrated by research [7], expectations of the receiving society in respect of an allegedly inevitable growth of crime among immigrants are often higher than the real statistics (which, by the way, can result from the securitisation of socio-political discourse).

However, the situation in Europe itself is far from being perfect. The EU expansion by including Bulgaria and Romania seriously complicated the situation. Due to the fact that all citizens of the EU should, in theory, have equal rights, the attitude towards them should be an attitude towards representatives of society being at a certain, sufficiently high, level of development. Nevertheless, it is hard to demand from Romanian Gipsies to comply with the European standards, same as it would be hard to demand the same from black migrants of the Central Africa. Problems of sociocultural integration are, therefore, a part of compensation for politicisation of the issue of the EU expansion.

The dilemma, in its essence, has no solution. It seems impossible to wait for citizens of less socially developed countries to increase their social development level to the average European level, same as it is difficult to expect that Mexican immigrants in the US comply with the American standards of law apprehension. The only alternative to the wait is to strengthen the government's control of society in general, which results in the reduction of the level of protection of individuals from arbitrary government.

Compensation for Moral Damages

Simultaneously with the tendency towards "disciplining of masses", we observe another, opposite trend — expression of freedom in the areas of social life that were under prohibition or, in any event, were not encouraged. For example, recognition of same-sex marriage. It gives a strange feeling of a dual process — we have the strengthening of police state, on the one hand, and, on the other, the spread of ideas of "libertinage" among the citizens of this police state, with vivid demonstration of tolerance for what was prohibited or disapproved by society yesterday. It will now suffice to recall the winner of the 2014 Eurovision Song Contest or legalisation of same-sex marriage in the US, Netherlands, Belgium and other European countries.

Can one believe that these two processes are connected between each other in some way? We can find an answer if we consider the structure of Western society in general, mainly, from the prospect of the relationship between the elite and middle class and the immigrant population or outcasts beyond the "civilised" society (terrorists, radical islamists, religious zealots, etc.).

"Securitisation" of society happens mainly in the interests of the elite and middle class, ensuring their safety. This safety is challenged, firstly, by the masses of lumpen-like immigrants whose appearance on the political arena of developed countries is related with the globalisation process and, secondly, by radical groups from the outside. Thus, the ideology of a "fortress besieged" is formed, which leads to the strengthening of control at the border, granting security services greater powers and taking tough internal security measures. The process of destruction of traditional values occurs due to the great difference between the cultures of immigrants and natives of developed countries. As a result, the destruction of the sociocultural unity of standards and rules of conduct in society leads to the situation where one can expect anything from anyone. Thus, it results in a many-fold increase in the perception of risks (although, objectively, these risks may be not so high) и expectation of threats. The destruction of cultural stereotypes cannot but affect all areas of life. The peaceful "burger's" life becomes a victim of globalisation while the necessity to control criminal groups results in the restriction on individual freedom. On the other hand, these, quite clear but sometimes painful, restrictions may not go without compensation, which is the increased tolerance for types of behaviour that were prohibited in "old good times."

These processes are especially vivid in the US. The country with its multiple conservative protestant sects is one of the leaders both in establishing control and "disciplining" behaviour of its citizens and in widely understood tolerance for what was thought to be deviant behaviour not so long ago. The US are known for the longest sentences for crimes (which apparently fits the "protestant" moral) and extremely high numbers of prisoners — many times more than in European countries per capita (although the US population is less than 5% of the world population, American prisons account for about 25% of all prisoners in the world [8]). The US security services have had an official wide access to private life of individuals for the last 15 years (by virtue of the Patriot Act).

At the same time, the US removes a number of restrictions, for example, for LGBT communities and expresses increased tolerance for the use of soft drugs.

Thus, we become witnesses of a far-reaching system of relations in society. On the one hand, the system of "conservative values" is changing. On the other hand, it is replaced by another system, whose shape is just being formed but which includes principles of "political correctness" and tolerance for minorities. If before these values were localised in narrow subcultures (for example, in the university environment), today they become increasingly widespread.

Russia is not an exception to this trend, although the traditions of liberalism do not have such deep roots and such a long history here. The repeated terrorist acts in Russia in the 1990-2000s and development of an international trend towards the increase of security measures contributed to a noticeable toughening of controls. The development of technology provides an opportunity to spy on private life of individuals at the same level as in foreign countries. In theory, the Constitution of Russia prohibits any violation of communication secret without a court order. However, in practice all communication operators are obliged to connect the Investigative Operations Support System (SORM) allowing the Federal Security Service (FSB) and authorities of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia to wiretap any subscriber and obtain other information without a court order. In September 2014, the Large Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights considered a claim of the St. Petersburg journalist and human rights activist Roman Zakharov about the unlawfulness of the existence of such system. However, no award has been issued yet.

In July 2015, a bill was introduced to the State Duma (prepared by Alexander Ageev, State Duma deputy), which would allow to adopt a codified normative act regulating investigational operations in the sphere of invasion of privacy.

Russia also applies a sufficiently though system to control the movement of citizens. It was largely inherited from the Soviet times. Registration at the place of residence and place of temporary stay is mandatory. No travel by long-distance train or bus is possible without producing passports. Russia's immigration policy also becomes increasingly protective: in addition to the obligation to register and obtain all permissive documents to stay in Russia, an immigrant can be deported for any two administrative offences (for example, traffic offence or crossing the road at the wrong place) and banned from entering Russia for a period of up to 5 years.

The "Pussy Riot" case, which has attracted worldwide attention, became a symbol of a thin line between the right to freedom of speech and self-expression for some and the right to protection of believers' feelings for others. The sentence publicly supported by the President evidences that in Russia the tendency towards liberalisation in the sphere of freedom of self-expression is not yet visible. The same situation is with sexual minority rights, evidenced by multiple refusals to approve gay-pride parades and the 2013 law on prohibition of gay propaganda criticized by European and American human rights protectors [9].

So, why does Russia develop, on the one hand, in line with the general trend towards "securitisation" without, on the other hand, creating mechanisms for compensation for "moral damage"? Three aspects seem to be important here. Firstly, the necessity to toughen control is perceived by society as objective and is not publicly criticised because Russia has been in the state of a continuous counter terrorist operation in the Caucasus for over 15 years and society regularly experiences deep shocks from the cruelty of committed terrorist acts. Secondly, Russian society is indeed quite conservative: it does hold much truck with the discourse of the necessity of a "strong state" guaranteeing "order" and share traditional values. Thirdly, Russian society still believes that the saying "the severity of punishment in Russia is compensated by the non-mandatory nature of its execution" is right. Introduction of high penalties often does not arouse indignation because everybody knows that in the Russian conditions, with the high degree of inefficiency of agencies, such as the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) and State Traffic Safety Inspectorate (GIBDD), and availability of corruption mechanisms, it is impossible to track violations. Moreover, the very perception of punishment as not being inevitable and constituting a "compensational" mechanism makes other easing unnecessary.

Back to the Middle Ages: the End of "Globalisation with a Human Face"

So, how is this fight for the rights of minorities connected with the system of toughening punishments and the general trend towards the "disciplining" of society? Apparently, the point here is not in changing the values but rather in a deep ontological shift in people's minds. The society agrees [10] to additional restrictions, to termination or weakening of certain freedoms in exchange for greater safety, with this safety available equally to all members of society if they obey and do not behave aggressively. Aggression, though, will be severely punished.

In practice, such society disciplining policy was tried in Singapore, which fined smokers a few hundred dollars for throwing a cigarette butt on the street. It is clear that implementation of such policy requires constant surveillance of each member of society, which narrows considerably the right to privacy. However, such a society is "securitised" to the maximum extent and such "securitisation" gradually becomes a world trend.

One must be aware of deeper consequences of such "securitisation". A society characterised by "aabsolute safety" reminds an ant colony. In other words, assurance of equal safety for everyone results in a habit to reject a risk by most of members of society (with the exception, of course, for those who serve to ensuring this safety). As a result, creativity of most of its members drops while the society itself transforms into a tough authoritarian structure.

It should be noted that it is not an accident that many "anti-utopias" of this sort have appeared on TV and cinema screen for the last two decades. The features described using these means of mass influence are very much similar to those of the Singaporean autocracy, with exaggerations being an intrinsic part of the fiction.

Naturally, such society is very far from the "liberal ideals" but, in a sense, it is a n example of reduction of these ideals to absurdity. The fact is that the "liberal ideals" are self-contradictory. On the one hand, they suggest freedoms of expression of one's beliefs and, on the other hand, the maximum safety for society. The line between freedom of self-expression and damaging social morals is very thin, which has been repeatedly demonstrated in the recent years.

Nevertheless, the general trend analysed in this paper cannot but raise concern. It is easy to imagine how this trend will affect the structure of international relations. In principle, it will not mean, as suggested by some analysts, the end of globalisation but it will certainly affect the globalisation process. In particular, development of "securitisation" in the world will imply the end of "globalization with a human face", which means that globalisation will turn its most negative sides to a human being. Universal securitisation will result in emergence of many "besieged fortresses" hostile towards one another and guaranteeing internal safety to their citizens in exchange for their freedom and privacy. Human race may enter a "new Medieval" period and a trend towards this is clearly visible in such phenomena as emergence of the "Islamic Caliphate", whose ideas are attractive not only to descendants of traditional Islamic regions but also to natives of European countries. "Caliphate" may well aspire to a new type of society. Having archaic and cruel order, hierarchy and control "Caliphate" may qualify for a new kind of society. However, this control will be explicit and open, justified by religious and ethical standards. Once the control in modern secular societies ceases providing benefits to the society, the medieval model of "Caliphate" will become an extremely attractive doctrine.

First published in Valdai Club

1. See the full text at: https://epic.org/privacy/terrorism/hr3162.html (date of request:6 July 2015).

2. Kua Kia Soong. 445 Days Under the ISA. Kuala Lumpur: GB Gerakbudaya Enterprise Sdn Bhd, 2010.

3. Agamben G. 1998. Homo sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford.

4. Obama on Surveillance, Then and Now // The New York Times. June 7, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/06/08/us/politics/08obama-surveillance-history-video.html?_r=0

5. The French Parliament Expanded the Powers of Security Services // Russian Gazette. 6 May 2015. http://www.rg.ru/2015/05/06/france-site.html (date of request 7 July 2015).

6. The Fight Over Canada's Patriot Act // The Foreign Policy. 24 April 2015. http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/04/24/the-fight- over-canadas-patriot-act-bill-c-51-canadian-anti-terrorism-legislation-stephen-harper-bill-c51/

7. How does immigration affect crime? // The Economist, 12 December, 2013. http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist- explains/2013/12/economist-explains-10 (6 July 2015); Crime doesn't rise in high immigration areas - it falls, says study // The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2013/apr/28/immigration-impact-crime (6 July 2015).

8. Joshua Holland, Land of the Free? US Has 25 Percent of the World's Prisoners // http://billmoyers.com/2013/12/16/land-of- the-free-us-has-5-of-the-worlds-population-and-25-of-its-prisoners/

9. http://ria.ru/politics/20130630/946660179.html

10. See, for example, the American society's attitude towards the US Government counter terrorism policy: The War on Terror: Ten Years of Polls on American Attitudes // https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Political-Report-Sept-11.pdf

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |