How to Overcome the Fresh Water Crisis in the Gulf

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia

The population of the Arabian monarchies is expected to reach 59 million by 2025 and 72 million by 2050. As a result, water seems to be becoming even more important as a strategic resource than hydrocarbons. One ton of fresh water is already more expensive than a ton of oil in this water-scarce environment, meaning that water security is a key prerequisite for the region’s future development.

The population of the Arabian monarchies is expected to reach 59 million by 2025 and 72 million by 2050. As a result, water seems to be becoming even more important as a strategic resource than hydrocarbons. One ton of fresh water is already more expensive than a ton of oil in this water-scarce environment, meaning that water security is a key prerequisite for the region’s future development.

Water Supply

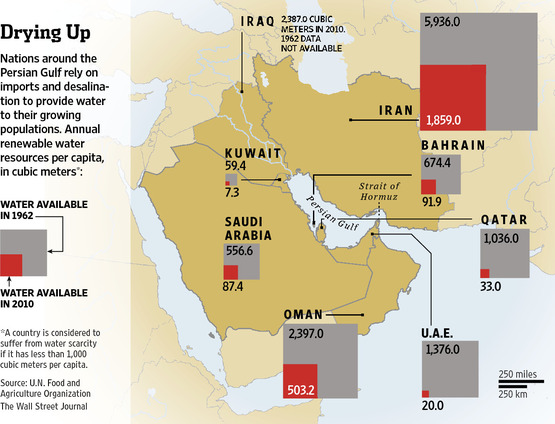

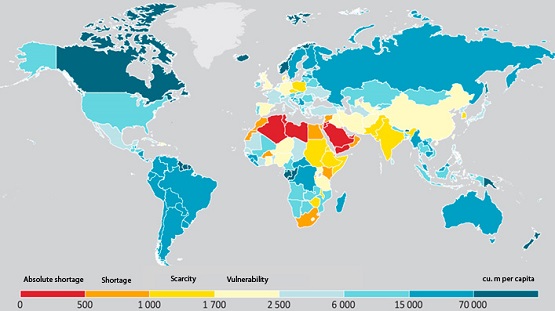

Except for Oman, all Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are very short of renewable water resources (see Figure 2). This situation is exacerbated by the region’s arid climate, scarce rainfall, high evaporation rate, and the predominance of non-renewable subsurface water.

Globally, the per capita renewable water supply threshold is 1,000 cubic meters a year, while in the Gulf countries this figure is, on average, 92 cubic meters, with the lowest level found in Kuwait – at 7 cubic meters – and the highest in Oman – at 482 cubic meters (see Figure 2).

All countries in the region rely on strategic subsurface resources. The years 1974-1990 saw a regional tussle over access to water in the Al Buraimi oasis – rich in both subsoil water and oil. In 1974, Aramco began drilling in this area east of Abu Dhabi on the border between the UAE and Oman, irking the British who viewed the territory as part of Abu Dhabi. That year, Saudi Arabia recognized Abu Dhabi’s right to Al Buraimi in exchange for recognizing a part of Qatar as a Saudi land. Consequently, Qatar was cut off from the UAE and the Saudis won access to the Gulf.

The Gulf states’ deep subsoil water reservoirs hold an estimated 2,330 billion cubic meters, with just 2.7 billion cubic meters of that classed as renewable (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.Renewable water resources and average per capita consumption, cubic meters a year

Source: www.strategyand.pwc.com

Today, the populations of Bahrain, Qatar, and the UAE have full access to fresh water. In Kuwait this figure is 99 percent, while the lowest indicator is found in Oman: just 86 percent of people in rural areas and 96 percent of those in cities (1, 2).

Dynamics and Trends in Water Consumption

With water supply running low, average water consumption in the region exceeds supply ninefold. The largest gap between supply and demand is seen in Kuwait – where demand exceeds supply by a factor of 63, and in the UAE – by 39, while in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Qatar the figures are more modest (see Figure 3).

All countries in the region rely on strategic subsurface resources. The years 1974-1990 saw a regional tussle over access to water.

Fresh water consumption is rising due to the expanding population, urbanization and economic growth, so this soaring demand for water combined with its absolute deficit cannot but generate serious concern. According to forecasts, by 2020, water demand in Saudi Arabia and Qatar will have doubled and tripled, respectively, from 2000 levels.

In addition, this water shortage is further compounded by poor management of this scarce resource. Excessive consumption of water, despite its obvious deficit, has become a grave problem, as in most Gulf countries per capita water use is several times above the global average. The emerging middle class over-consumes water. The construction of private swimming pools, gardening, and golfing combine with the absence of limitations and the existence of subsidies to encourage water consumption. Daily per capita water use in the Gulf countries ranges from 300 to 750 liters. For example, an average UAE resident uses 550 liters a day, while water use figures for a someone in the UK or Germany are 193 and 149 liters respectively.

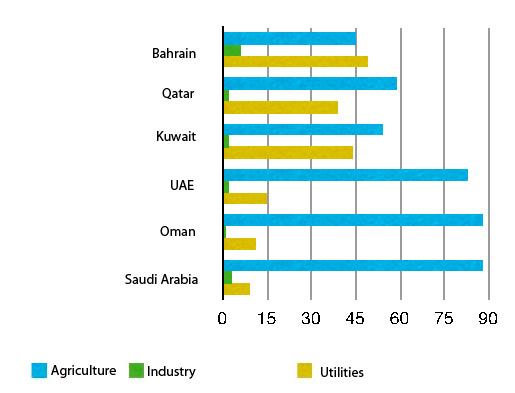

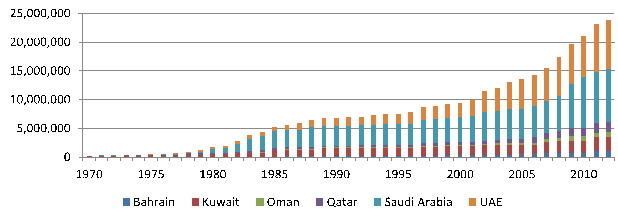

The region's growing economy is also pushing water demand upward (see Figure 4).

Directing most of the water into agriculture may go some distance toward solving food security problems but is ineffective, as the agricultural sector generates less than five percent of regional GDP. The Arab monarchies’ economic prosperity is built on oil production and exports, though they have been diversified through the establishment of energy-intensive sectors such as oil refining, petrochemistry, and aluminum production. If they are to succeed in achieving further growth, they will have to solve the water supply deficit issue.

Ensuring Water Supply

With water supply running low, average water consumption in the region exceeds supply ninefold.

Since surface and subsurface water sources fail to meet demand, the Gulf states are pursuing other avenues to augment supply. Currently the region is leading the world not only in water consumption but also in desalination, as GCC economies boast almost 60 percent of global desalination capacity.

The first regional desalination plant was built in Kuwait in 1951 in developments that were intertwined with oil production. It was the oil boom that made it possible to build costly desalination installations. Arab News reported that, each day Saudi Arabia uses 1.5 million barrels of oil for desalination purposes (1, 2). Investments in desalination jumped in the early 1980s, so today Saudi Arabia and the UAE are both regional and global leaders in the field (see Figure 5). Last April, Saudi Arabia commissioned the world's largest plant, worth USD 7.2 billion, generating one million cubic meters of fresh water and 2.6 MW of electric power a day.

In 2011, there were 294 desalination facilities in GCC countries, 128 in Saudi Arabia, 98 in the UAE, 24 in Kuwait, 19 in Oman, 13 in Qatar, and 12 in Bahrain, which pump the desalinated water to factories, farms and households, in addition to producing potable water.

In the coming five years, the Gulf countries plan to invest about USD 100 billion in desalination, while over the 2005-2014 period Kuwait spent USD 5.28 billion on water production.

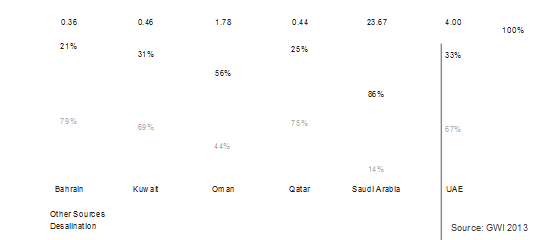

The regional leaders in desalinated water consumption are Bahrain (79 percent of total water use), Qatar (75 percent) and the UAE (67 percent) (see Figure 6). However, desalination does not yet offer a universal approach to providing people with potable water, as it is unpalatable and contains hazardous substances.

Waste water treatment and reuse offer another source of fresh water, and practically all Gulf states employ developed water treatment systems. In 2009, waste water collection in GCC countries reached an average of 52 percent, with 70 percent in Bahrain – which has set itself the target of achieving 100 percent by 2015 – and 15 percent in Oman. Bahrain also boasts the region's highest waste water treatment rate (100 percent), while the figure in Kuwait is 87 percent and in Saudi Arabia it is 75 percent. Oman and the UAE lead in the reuse of treated waste water with 100 and 89 percent each respectively.

Figure 6.Share of desalinated water in total water consumption, percent per year

Source: www.strategyand.pwc.com

The construction of water storage tanks is also an imperative from a water security perspective. If desalination plants stop working, Qatar would be left with resources covering less than 36-hours of demand and the UAE would have sufficient reserves to last 48 hours. GCC countries allocate huge sums to increasing water reserves, with Qatar allotting USD 900 million to construct storage facilities providing seven-days-worth of water reserves by 2017.

Imports are also a source of fresh water, and potable water is imported to GCC countries in bottles or for in-situ bottling. There have been discussions of projects involving the transportation of water from neighboring countries. In 1986, proposals were made to lay two pipelines from Turkey that would carry water from the Seyhan and Ceyhan rivers. There were also plans to transport water from the Nile across Saudi Arabia to GCC countries. In 2003, Kuwait and Iran signed an agreement on water delivery by pipeline. There was also a preliminary study for the transportation of water from India across the Gulf of Oman and on to the GCC countries via pipelines.

Excessive consumption of water, despite its obvious deficit, has become a grave problem, as in most Gulf countries per capita water use is several times above the global average.

As of now, GCC countries have agreed to build a pipeline that will be almost 2,000 km long supplying the entire region in a project worth USD 10.5-billion. The project incorporates the construction of two 500-million-cubic-meters desalination facilities that would deliver water to parts of the GCC in need of desalinated water.

Rational water use is another promising route, combining of the promotion of water saving, the introduction of water-efficient technologies in industry and agriculture, and also higher water tariffs. By 2017, Qatar plans to cut personal water consumption by 35 percent. Abu Dhabi has recently banned the use of subsoil water for growing fodder cultures. Saudi Arabia is gradually reducing grain production while also encouraging firms to invest in countries with solid farming potential.

In order to meet food demand, in 2007 GCC states started investing in farming abroad – primarily in developing countries. Far from all attempts were successful. For example, the UAE investment company Jeenan bought 67,200 hectares of land in Egypt to grow fodder for cattle back home but the unexpected 43-dollar export duty, strikes, and diesel fuel shortage prompted the company to redirect its efforts to the Egyptian market. The Saudi Star bought 10,000 hectares for rice cultivation in Ethiopia, but in 2012 its workers came under rebel attack and five of them were killed.

Today, GCC states are set on diversification, buying agricultural lands across the world – in Africa, East Asia, the United States, and Australia – in order to save water domestically by growing foods abroad.

Currently the region is leading the world not only in water consumption but also in desalination.

More exotic methods for fresh water production are also applied, with the UAE experimenting in the formation of rainclouds back in 2011 when the government allocated USD 11 million for a related project.

Despite diverse attempts to reduce their water dependence, the GCC states are still chiefly reliant on desalinating water from the Gulf, which is increasingly suffering from oil spills, red tides, and radioactive waste. Another risk associated with continuous desalination comes from power shutdowns, natural disasters, hacker attacks, and military conflicts. Several Kuwaiti desalination plants were destroyed during the Iraqi assault in 1991, which also saw 732 oil wells set on fire and the dumping of 816,000 tons of crude into the Gulf, jeopardizing both the desalination operations in Kuwait and the entire regional subsoil water pool.

Russia’s Opportunities

With GCC interest in water and food security running high, Russia seems able to offer several forms of mutually beneficial cooperation.

Despite diverse attempts to reduce their water dependence, the GCC states are still chiefly reliant on desalinating water from the Gulf.

One possibility lies in the export of drinking water. Russia is the world’s second largest holder of fresh water reserves and could easily sell some of its renewable water to other countries, for example by providing the GCC with bottled and unbottled water, both standard and quality grades. Beverages such as juices, fruit drinks, etc. seem another promising option, since they carry little production risk. The plants, water carriers and infrastructure required need massive cash injections, which could come from the Arabian oil exporters. Under this scenario, Russia would receive much-needed funds for industrial development while the GCC countries would gain access to another water source. The Rosvoda Corporation seems fairly energetic in efforts in this area, as it has announced plans to build a 50-million-a-year top-grade water production plant and is negotiating project financing with numerous investors, including those in the Gulf.

Water treatment offers another way to expand Russia’s interests in the GCC area as the country is in a strong position to provide advanced technologies for waste water treatment that are well-reputed in the region. Working in Saudi Arabia for about eight years, in 2006 the company ECOS successfully completed its maiden project to upgrade sewage treatment facilities in Riyadh. In 2013, ECOS won the contract for the reconstruction of the Saudi capital’s main purification facilities, which envisages raising their capacity to 500,000 cubic meters a day and boosting output water quality to reuse level.

Russian firms may offer innovative space solutions for monitoring contamination in water basins and surveying water reserves. The Russian market also boasts numerous companies that have built solid reputations in developing and supplying software for geo-information systems, cartography, geodesic and navigation equipment and instruments, providing remote sensing data, and carrying out surveys, which have already attempted to enter GCC markets.

The lease of Russian farming land also seems promising, as another avenue for beneficial cooperation that fits with the GCC policy to diversify investment in agriculture abroad, reduce water consumption and boost food security.

Interaction between Russian and GCC companies could be structured in a more sophisticated way, i.e. through exchange-traded funds, index investment funds, and mutual funds, with portfolios incorporating shares in water-sector firms. These entities already operate in industrialized countries, e.g. the Pictet Water Fund and Kleinwort Benson Investors, but also in developing economies e.g. Sanepar and Sabesp in Brazil, Thai Tap Water in Thailand, VA Tech Wabag in India, and Manila Water Company in the Philippines. Russia could join forces with GCC countries to employ these new financial technologies and invest in water surveys and infrastructure, water-efficient technologies, desalination, treatment, etc.

* * *

Although water security seems a major concern for the Gulf states, they do have the necessary financial, energy, managerial and human resources to provide their populations and economies with fresh water required to meet their capabilities and under their strategies. Their priorities will include improved water management, farming reform, attracting private funds to the water sector, enhanced financing of waste water collection and treatment, expanded water supply networks, and water reserve replenishment.

Desalination is likely to remain the main support for the fresh water supply, involving the continued expansion of desalination capacity through the construction of new plants and the modernization of existing facilities. Prospects for water imports and transportation from neighboring countries are unclear due to social, environmental, and political risks.

The Gulf states will largely focus on collective action to counter the threat of severe water shortage, concentrating on transborder desalination and transportation projects, the establishment of a single groundwater database, and joint management of water resources. The development and adoption of a GCC-wide water strategy is likely to emerge as the next step toward improved coordination and efficiency in responding to regional water security issues.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |