Engineering the future with the Next Nostradamus

(votes: 1, rating: 2) |

(1 vote) |

Interview

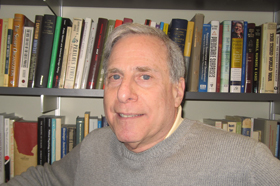

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Professor of Politics at New York University, built a computer model based on mathematical algorithms that can predict the outcome of complex negotiations and potentially coercive situations. The model successfully predicted political power shifts, terrorist attacks, coups, Iran’s nuclear future and so on. His work earned him the name “The Next Nostradamus”. In this interview Bruce Bueno de Mesquita talks about human behavior and the ways of engineering the future, shedding light on the logic behind his computer model.

Interview

Words can be interpreted in many ways, but mathematical formulas do not allow for such ambiguity. Rigorous application of mathematics in the study of politics brings clarity and weight to research. Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Professor of Politics at New York University, built a computer model based on mathematical algorithms that can predict the outcome of complex negotiations and potentially coercive situations. The model successfully predicted political power shifts, terrorist attacks, coups, Iran’s nuclear future and so on. His work earned him the name “The Next Nostradamus”. In this interview Bruce Bueno de Mesquita talks about human behavior and the ways of engineering the future, shedding light on the logic behind his computer model.

Interviewee: Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, Professor of Politics at New York University, consultant to government agencies and to private businesses

Interviewer: Maria Prosviryakova, Russian International Affairs Council

The ability to make predictions using game theory is by itself fascinating, but the real value is the ability to engineer outcomes that could be beneficial for the society. What engineered solutions are you most proud of?

Three decades ago I devised the strategy that got the former Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos to give up power peacefully and to step aside. I designed the strategy that got Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge to allow free elections in Cambodia that they knew they would lose. Additionally, I was very proud of having predicted both the coup against Gorbachev and that it would fail. I have to say that Henry Kissinger thought we would have to recognize the coup makers because it was a new reality. My analysis said they would be gone in a very short time and they were.

More recently - and I am sure many other people came up with similar results - I did a study in which I predicted that Iran would not design and test a nuclear weapon. In part because of that study the U.S. government changed its National Intelligence Estimate regarding Iran. I believe that helped to tie George W. Bush’s hands so that he did not attack Iran in 2007.

So, those are just a few highlights, there are others.

Game theory captures the logic of human behavior. What is necessary to know about human nature in order to make a prediction?

It is necessary to make some assumptions and to apply them rigorously and systematically:

- People are rational in the sense that they do what they think is in their best interest (they may be mistaken after the fact).

- People are self-interested. It is nice to think that people are concerned about the well-being of others. If you assume that people are self-interested, you are not disappointed very often, and, occasionally, can be pleasantly surprised.

In order to analyze what people are likely to do you need information about 5 things:

- For any given decision or any policy question you need to know who will try to influence the decision. And for those who will try you need the following 4 things (each of them in numbers):

- What policy outcome they currently argue for: not what in their heart of hearts they want, not what they are expecting to get, but their current bargaining position. You have to define an issue along a scale or continuum.

- How influential they could be if they tried as hard as they can (they probably won’t try that hard of course).

- How focused they are on the issue. That is how high a priority it is compared to other things on their agenda. That tells you something about how hard they will try.

- How resolved or how flexible they are. How committed they are to their point of view, even if it means defeat; or how open they are to changing their point of view to try to have a successful outcome even if it means not getting what they want.

If you know those things and have a dynamic model where all those variables can change value within the logic of the model over time, you can predict how negotiation and coercion will evolve. You can predict with a great deal of reliability what people will do and what the outcome will be; as well as what the outcome would have been had they acted differently. That is the way you can engineer the future.

Do you factor in culture and emotions?

No. Culture is probably captured by those variables by how they distribute in different settings. But if you know the variables’ values you do not need to know where they came from: whether it is culture, historical circumstance, etc.

As for emotion, we need to divide it into two components, because my model can predict emotional outbursts in the form of sudden violent or aggressive behavior if the emotion is strategically motivated. So, there is an emotion that is strategically induced. People use it as a strategy in a negotiation to alter other people’s behavior.

Then there is a raw emotion that is not calculated and not strategic. My models have nothing to say about that kind of emotion. I am sure it is important but I can only say that on thousands of applications the game theoretic models I have worked with have proven to be accurate about 90% of the time.

So, emotion is not the only source of error, but at most it is 10%.

What people say publically is their strategically chosen position, which does not always reflect their real position on the issue. Should one always try to identify people’s real positions?

I typically get my data from people who are experts on the problem. I do not ask them what is going to happen. I ask them about right now. One of the things I say to them: “When you are estimating, for example, a group of politicians’ position, what is your best estimate of what they say to their colleagues in the smoked-filled room?”

I am not interested in their public statements. So, people who follow any issue really closely, typically talk to enough people, they have a pretty good idea about what people are saying in private or what they are likely to say based on past experience. That is what I want to know. I do not want to know public posturing. But public posturing can be informative because in a model such as mine - that assumes people’s behavior is strategic - you can work out parameters around what they say in public that are consistent with how far off of that could they be in reality. That allows you to move forward in figuring out what they are likely to do.

What questions do you pose in order to obtain data for your model?

That is dictated by the theory. I do not make up new questions for each set of experts. They are the same: who are the players, how much influence could they exert, what they currently say they want, how focused and how flexible they are on the issue. They tell me lots of other stuff but those are the only things I need to know. Just those pieces of information in numbers go into my computer model.

The wrong data fed into the computer model is most likely to give the wrong outcome. Is there a way to make sure that the data is reliable?

When I assemble a group of experts I look for people who follow an issue really closely or who have (especially in my private sector consulting) a lot at stake. I am not looking for people with brilliant analytic insight. What is important for me is that they are very attentive to the facts on the ground at the moment.

There have been a number of controlled experiments, testing whether picking this or that set of experts makes a big difference. It does not. My undergraduate students do not have access to experts; they find the data online and get accurate answers as well. So, it is just a question of knowing what questions to ask and being able to evaluate whether you are finding consistent information. It is remarkable how easy it is - when you sit down with a group of experts - to tell whether they know what they are talking about or they do not. When people contradict themselves, I point it out.

There is a perfectly good test in the model of whether the data is garbage or not. People often think “garbage in - garbage out”; – and this is absolutely true. As well, they think that if you ask experts you get random judgment. Nonsense!

Since I am only asking about the current situation, I am not asking about their opinions of what will happen in the future. If the initial data do not produce within the model’s first period of prediction an accurate image of the current situation, then the data are no good. If the data produce an accurate image of the current situation then the model’s logic, the mathematical logic within it takes over. So, the outcome is based on sound data. I am very careful about getting quality data, because if I did not I would not have a good track record.

What skills does one require to be able to make predictions?

A good model, good mathematics, skills for collecting the data, good attentiveness. The art in this is framing the questions pertaining to the issues that you are going to analyze. Learning to ask people those questions in a format that does not elicit a yes-or-no answer, but a range of choices is important. Any intelligent person can learn to do this, as it is not some deep mystery. The logic and math are worked out, it is just the question of feeding data. Of course, improving the model takes more skills.

According to CIA estimates, the accuracy of your models is 90%. What can make some predictions go wrong?

Many things can go wrong. I think the biggest source of likely error is some random shock that fundamentally alters the problem.

Say, one is analyzing Iran’s nuclear program and collected data today. Imagine that tomorrow Ayatollah Khamenei has a heart attack and dies; and Jafari is going to the funeral and gets hit by a bus. The entire political structure of Iran’s decision-making group would be fundamentally changed by those events. So, it is likely that the analysis - in which those two people were critical actors in the dataset and then were removed - would be wrong.

But there are things you could do about that. You can randomly shock the data to see how big a disturbance it takes to alter the result. So, you have to be attentive to that.

Surely, there are circumstances where emotions matter. I think it never happens in big foreign policy questions, but in some business questions and litigations it certainly does.

As well, you may have bad data. But you should be able to recognize that when it does not reproduce the current situation.

Of course, there are problems for which this particular model is not the right way to think about: for example, I can not predict the stock market. This is a model of negotiation in the shadow of the threat of coercion. Stock markets involve neither.

So, those are some of the things that could go wrong and they collectively account for the roughly 10% of error.

The predicted outcome might be different from the desired one. What are the ways to engineer the desired outcome?

The answer to that depends on the particular question and the particular data. There is not an off-the-shelf common solution to every problem but there are lots of different things you can do.

If you are not getting the outcome you desire, you might experiment with taking a more moderate or more extreme initial position to alter how people perceive you. You might experiment with fewer groups of allied people showing a common united front to show different division of opinion. You might experiment with pretending to care about the issue less than you do, because it will change their perception of how central this is to you; which in turn might change their perception of how hard they have to work to get your attention. So, there are lots of different sorts of things you can do in various combinations of them.

Model identifies various combinations of errors that people make in their negotiating and identifies how to correct them. So, before anybody actually gets into the negotiating room, it allows us to simulate through the model’s logic what would happen if you did this instead of something else and what produces the best result for whatever goal you have in mind. That is the way to engineer any problem.

Professor Bueno de Mesquita, thank you so much for this interview.

(votes: 1, rating: 2) |

(1 vote) |