An Impalpable Presence

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of Political Science, Director of the Centre for Comparative Governance Studies, Saint-Petersburg School of Social Sciences and Area Studies, HSE Campus in St. Petersburg

The idea that Russian social sciences (in particular, political science and international relations) should be more open to the international community long ago lost its novelty factor. The most important, if not the main, measurement of such openness are publications by Russian researchers in the Western academic journals. Of course, you can continue believing that everybody here is, by default, working at a higher international level. However, these illusions are only good for "internal use", the outside world will never know about it.

The idea that Russian social sciences (in particular, political science and international relations) should be more open to the international community long ago lost its novelty factor. The most important, if not the main, measurement of such openness are publications by Russian researchers in the Western academic journals. Of course, you can continue believing that everybody here is, by default, working at a higher international level. However, these illusions are only good for "internal use", the outside world will never know about it.

Today in Russia, there are dozens of political science and international relations departments and divisions in universities and colleges, which each year produce thousands of young professionals and dozens of new doctors. But the quality of the university graduate’s training and the professional level of those who teach them are very different. Very few Russian foreign affairs and political scientists regularly (or even occasionally) are published in the Western academic journals. Most of the talented young professionals leave science for good. You could link these dismal trends solely to the lack of public funding. But that is just naive.

Why do we have so few good, competitive texts worthy of publication in Western journals? And why are even these texts difficult to turn into articles, i.e. to get published?

Education, our whip...

It is, above all, the knowledge of the current theoretical and methodological approaches and the ability to apply them correctly.

One of the most obvious reasons for the low competitiveness of Russian political scientists and international relations is rooted in education. To get a "normal" education in these fields, it is necessary to travel to the West. There are very few people who have received this kind of education and returned to Russia to work "in science". As for the Russian political scientists and international relations senior and middle generations, their diverse educational background (some from philosophers, others from historians, some from economists, and others from geographists) is a real obstacle to the promotion of publications.

Despite joining the Bologna process, Russian education in the social sciences is still not competitive. Here is a small but very typical example. There is a significant and almost universal shortage of people who can teach quantitative methods to political scientists. There are, on the one hand, many excellent mathematicians and statisticians, who do not have political science experience (and sometimes they are denying its existence), on the other hand, there are a lot of political scientists, who do not know the appropriate methods. This problem was identified a few years ago, but it is being solved very slowly and mainly within the capital's universities.

Thus, we are interfered not as much by the fact that we are "not smart enough", but by our very education and its nature. Although, the general mood amongst Russian intellectuals regarding the "intellectual climate" in modern Russia is almost panicky, we undoubtedly do have scholars, people who have brilliant education in social sciences. However, the nature of that education (or more precisely, self-education), is a huge amount of reading and unconventional, deep thoughts which does not help them get published in Western journals. There is a need for other professional techniques, other qualifications or, as they say, competences. It is, above all, the knowledge of the current theoretical and methodological approaches and the ability to apply them correctly. So that access to the outside world, for such specialists is best achieved through publication of collected volumes, published by the Western publishing houses, or does not achieved at all.

We are the "Russian experts"?

The question arises: what can we, the researchers, who, for the most part, do not have today's competitive education, offer to the Western science? Apparently, it is something we are experts in, that is our knowledge of Russia. The response from the West will be clear: it is not needed whatsoever (or barely needed).

We must consider the fact that purely Russian studies are, above all, publications published only in the specialized journals, with a low circulation.

Firstly, the West has enough experts on Russia and due to the permanent exit of Russian scientists from the country abroad there is more and more of them. Currently, more than 900,000 Russian scientists are working in the USA, about 150,000 in Israel, 100,000 in Canada, 80,000 in Germany, 35,000 in the UK, and 3,000 in Japan. [1].

Secondly, and more importantly, such expertise knowledge by itself is worth little. The expertise and the results of academic research should be fundamentally different. So from the "publishability" point of view of referred articles in the scientific journals Russia may be a case in the article, whether it is an article on political parties, electoral systems, or on the nature of foreign policy, but it cannot be the main and only object of the study.

So far, Western scientists see Russian political scientists and international relations primarily as "suppliers" of expertise on Russia which, of course, is very useful but is not a substitute for academic research. Western scholars prefer occupying themselves with these studies.

Furthermore, we must consider the fact that purely Russian studies are, above all, publications published only in the specialized journals, with a low circulation.

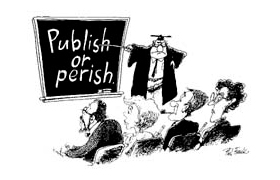

The problem of incentives, "publish or perish"

There are certain rules, on which the world's academic practices are based, and when accessing the international markets, whether we like it or not, we have to stick with them. It is clear that these rules have been established and accepted by the academic community long before Russia "opened up" to the world.

The availability of publications in the international journals is indispensable, and an imperative condition of scientific activity in New York, Berlin and Beijing. However, in most of the Russian institutes so far only a few people are seriously concerned with having publications in Western journals on their curriculum vitae. It is no secret that the famous Western principle of "publish or perish" is still seen by many Russian scientists as unworthy of "true science". They frankly believe it to be a ridiculous notion that their career may depend on referred articles in the international journals. We struggle to maintain momentum. And this is a very favorable point of view, since to get such publications is difficult. The standard life cycle of research is long: from the identification of the research problem to the solution in the form needed for publication in referred journals may it take several years.

So far, Western scientists see Russian political scientists and international relations primarily as "suppliers" of expertise on Russia which, of course, is very useful but is not a substitute for academic research. Western scholars prefer occupying themselves with these studies.

Obviously, a fundamental change in the situation is required, first a generational change that has not yet occurred, and secondly, a system of incentives that would motivate researchers to conduct competitive research and therefore, would open the way for them to such publications. Payment of bonuses for such publications is a tool which is now beginning to be used in our universities but it is not the only guarantee of success. It would be reasonable to provide financial support with other kind of incentives, such as payment for the authors participation in conferences and seminars.

Periodicals with a high circulation reject nine out of ten manuscripts (many of them are not even considered) based on reviews. This means that the incentive for publication should take into account the ranking of the magazine and the quality of the article.

To solve the problem of "unpublishing" the following are recommended:

- to look for sponsors in the West and get published together with them;

- to actively discuss the preliminary results at workshops and conferences prior to publishing an article (most of the articles discussed at conferences, are available online, thus such an article will be criticized by the academic community before the authors send it to some world famous journals);

- to invite the editors of the leading journals to give lectures on how the editorial selection process works (as done in all Western post-graduate studies);

- to create own peer-reviewed journal in English in every area of social studies (for the first time it is possible to request a review by foreign scientists, and then with the increasing reputation, invite temporary editors for special issues on the same topic).

You may have to pay referees, for example,

"The temptation environment" and the measure of success

Let's not forget about how we evaluate professional success. This success paradoxically, in the academic environment, is largely measured by the degree of publicity, and the degree of “belonging to the preferred set”. It is important that success in the professional, academic community itself is valued very low and is not a measure of total success in life. Only when applied to publicity. Writing good research papers is not enough. To be a great lecturer is almost irrelevant. This will not make a name for you. So given a very low status of the academic community the monstrous efforts made by many of our scientists to maximize their publicity are excusable and understandable. But it is of general concern for many reasons.

Firstly, the wide public work of scientists by default is confirmation and fixing of the low status of the academic scientific community, scientists send out a signal of their agreement with the state of things.

Secondly, researchers are shifting priorities from the really important (the production of new knowledge) to the completely insignificant ones from a professional point of view. It is a pity when good brains do not produce a good product. And there is a need to make a choice: combining academic articles and flashing on television is hardly possible.

Thirdly, the standards for science and success criteria are actually set from the outside, from the public sphere. It is fundamentally wrong to apply these criteria to the academic community very quickly, especially among young scientists. And it turns out that the professionalizing the academic communities (at least in many of the social sciences) has not taken place yet, but the so-called de-professionalizing is already in progress.

Finally, vigorous public activity poses the most important big question, "academic freedom". Maintaining this freedom is both a challenge for the academic community, and its main feature. After all, the work of academics should be about conducting research, results of which no one knows in advance. So, the fundamental condition must be observed: researchers should be free to choose the way they work and independent of political and social preferences. The temptation of publicity makes this an almost impossible condition.

The temptation of publicity cannot be avoided in universities. In Russia, it is a pleasure and honor to have famous public figures in the teaching staff. In the West, university policies vary: some recognize the usefulness of external to the University publications by the academics (in the vast majority of cases we are talking about expertise and nothing more) since it advertises the university, others universities do not tend to take into account the external activities. But it is impossible to imagine that a professor or researcher will be invited to work or be evaluated by the University based on the number of their appearances in the media and participation in TV programs. In Russia it is becoming standard practice.

Conclusion: farewell to illusions

So there are no more illusions about the high quality education and high quality social sciences in the best universities and institutes in Russia, and consequently the high place of Russia in the "world ranking". However, getting rid of this illusion is not enough. The situation is very, very complex: we are hindered by the inertia (the nature of our education and the rejection of Western standards), while simultaneously new times present new challenges. “An impalpable presence” of Russian scientists in the Western scientific journals is, of course, part of a much broader problem with Russia's competitiveness in the world today. And in order to bring about a fundamental change in this situation, if we are unhappy with it, nothing but rejection of the myths and the new system of incentives can be offered for its solution. In any other case, the prospects of our development will be extremely limited.

1. Uskova O. Brain Hunters / / Vedomosti, 07.05.2010

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |