Russia should take the leadership of International Criminal Court reform

In

Log in if you are already registered

Denazification is the main mission of the special military operation in Ukraine:

The goal is to bring to justice the radical neo-nazis responsible for crimes in Ukraine in the last 8 years:

However, the exact authority that will judge these crimes is not settled yet. In a recent interview, Russian Investigative Committee Chairman Alexander Bastrykin said it was an “open question”. DNR Foreign Minister Natalya Nikorovna announced a future international tribunal, still “under preparation”.

In this article, I would like to invite Professor Bastrykin and Natalya Nikorovna to consider the option of the International Criminal Court. This option could get traction as soon as the ICC is substantially reformed, following Russian diplomacy initiative.

The Soviet heritage of the International Criminal Court

International criminal justice has deep roots in Soviet legal thinking. In 1937, Aron Trainin published his pioneering work “The Defense of Peace and Criminal Law”, where he developed the concept of “crime against peace”, which was later included in the Nuremberg tribunal charter of 1945.

At Yalta conference, Joseph Stalin insisted to establish this international tribunal, while Winston Churchill preferred summary execution of Nazis.

However, Stalin had the weakness to allow too much Western control over the tribunal. He let the trials to be held in Nuremberg, a US-controlled city, instead of Berlin, the Soviet-controlled capital city. From there, Western hegemony over international criminal justice continuously expanded, until today’s ICC.

Russia can be a leader of global justice again

Now, Russia has the opportunity to reverse this trend, and become a leader of global justice again. Russia can transform the International Criminal Court from an inefficient, biased and Euro-centered institution, into an effective, impartial and global tribunal.

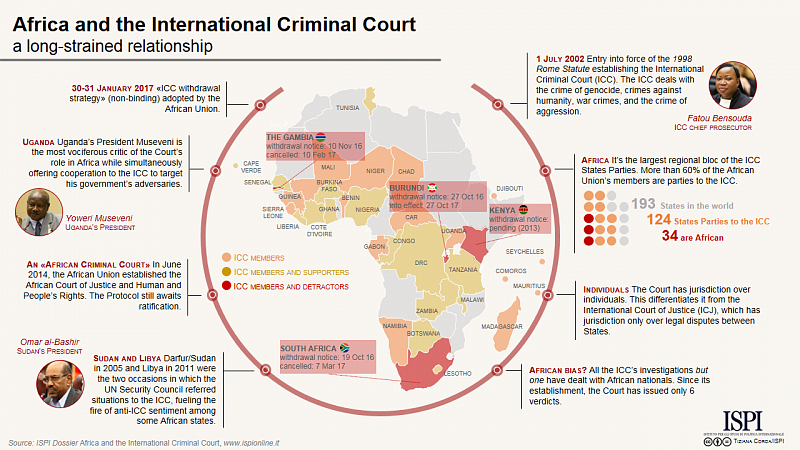

The existing ICC is widely criticized around the world. Burundi and Philippines withdrew from the ICC, Kenya and South Africa almost did, and the African Union even called for a mass withdrawal.

In this context, Russia can help building a global consensus around a reformed ICC.

Russia can de-westernize global justice

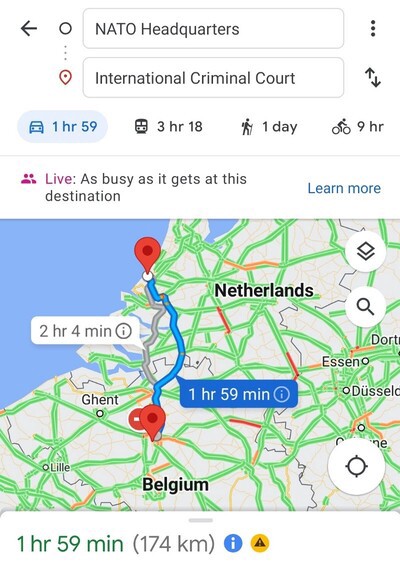

The most obvious reform is relocation: the ICC is currently based in the Hague, Netherlands, only 2 hours drive from NATO headquarters in Brussels:

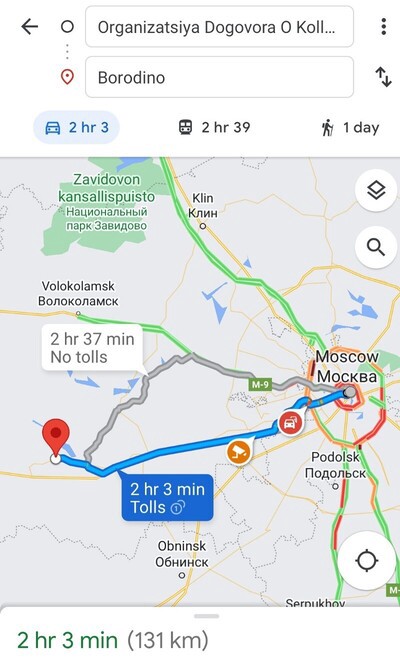

Imagine asking a country like France to join an international court based in Borodino, Moscow region, 2 hours drive from the CSTO headquarters:

Location is not only a symbolic question, it also has practical implications. The court needs to avoid pressures from any party involved. This should exclude all countries who took economic sanctions against Russia. Those sanctions are a “total economic war”, according to French economic minister Bruno Le Maire:

This still leaves a lot of options for choosing a neutral territory. Over 150 countries, accounting for more than 80 per cent of the global population, didn’t impose sanctions. Russian isolation is a Western illusion:

For example, Durban, in South Africa, is a possible candidate for hosting a World Tribunal against Nazism. Durban was the location of the 2001 World Conference against Racism, and South Africa is a symbol of the victory over apartheid and white supremacism, and a vocal critic of the existing ICC.

Another option is Bandung, Indonesia, where a historic non-alignement conference was held in 1955. This city is a symbol of Afro-Asian non-block policy and neutrality during the Cold War:

The city of Odessa, in Ukraine, has been suggested by Sergey Mironov, leader of “A Just Russia” political party. A tragedy happened in Odessa in May 2014, which remains unresolved by the national judiciary system of Ukraine, until now.

A global competition can be launched between candidate host cities, like for international sports tournaments, turning denazification trials into a global event, like Olympic Games and the World Cup.

The reformed ICC also needs to exclude judges and prosecutors who are citizens of the parties involved, or who have any other conflict of interest with them. There is a legal precedent: in 2020, the United States attempted to intimidate ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda by taking personal sanctions.

The new ICC chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, is a British citizen, so he needs to step down in order to rebuild the ICC. Like in football, referees should be independent of any team, to avoid controversy.

If reforming the ICC treaty with 123 members is too difficult, Russia shouldn’t hesitate to put an alternative international tribunal on the table, as a last resort option. Russians have a lot of negotiating power on the reform process, because they have skin in the game. Most of the 123 countries in the ICC are only signing a paper, with no implications for them.

Russia should invite Ukraine and the USA to join the reformed ICC

Russia should invite Ukraine to join this reform initiative, and overcome ICC critics in Kiev, who went as fas as to call the ICC a “threat to Ukraine in a hybrid war”. Ukrainian President Zelensky demanded the United Nations to “act for peace, or dissolve itself”. ICC reform is a chance for Ukraine to act for peace, and justice.

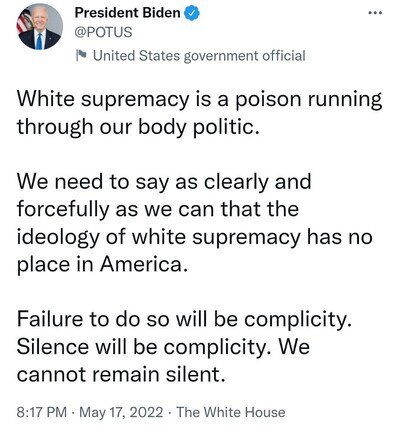

Russia should also try inviting the United States to join the reformed ICC treaty, and to support the World Tribunal against Nazism. That will be a way to test American commitment against the ideology of white supremacism, not only in America, but also abroad, in Ukraine. Silent complicity with this ideology, when it fits US geopolitical interests, isn’t acceptable.

ICC should start small, with pilot projects

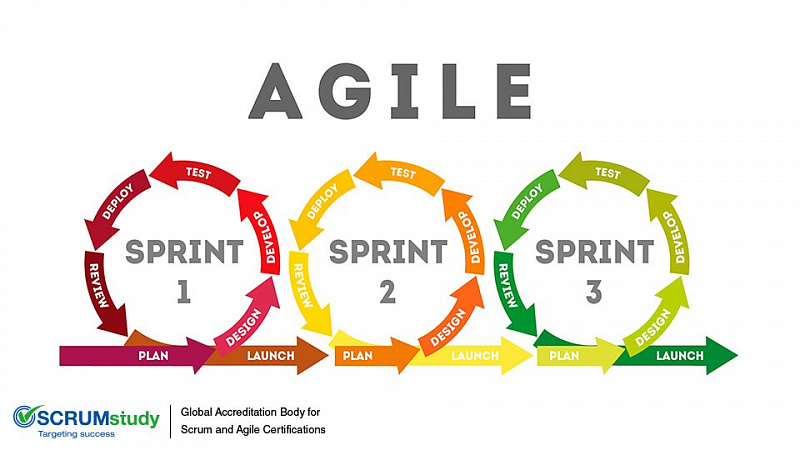

In practice, it won’t be enough to reach a global consensus on ICC reform. The new court also needs to really work as intended. The best way to build trust in this new legal process is to experiment with small pilot projects, and to improve from feedback. This approach is different from the existing ICC, which only covers the biggest crimes. Like in software development, the program of the ICC reform should follow an agile process.

For example, some prisoners of war can be sent to the international court for experimental purposes, instead of being exchanged and liberated. They can be judged for minor offenses. A zero tolerance policy can be applied to any breach of the rules of war.

Low-stake, high-visibility cases are the best to start with. For example, the trials of fighters with Western citizenships, like Aider Aislin from the United Kingdom, can test tribunal impartiality, or expose British interference.

Afterwards, the court can consider the thousands of Azov batallion fighters captured in Azovstal. They always asked for third-party intervention, so their “evacuation” to an international denazification tribunal, in Africa or Asia, is a possible answer to their call.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Russia can denazify Ukraine by de-westernizing global justice. ICC reform can be the first step in a larger diplomatic counter-offensive for Global Russia, a renewed concept of Русский Мир. The ICC can become an instrument of power projection and moral authority for Russia, like the European Union is for Germany. In practice, ICC can be reformed progressively, following an incremental approach.