Russia Increasing Role in International Drug Prohibition

In

Log in if you are already registered

For almost a hundred years the United States has been the primary instigator of international drug prohibition. Recent developments, however, have been challenging the Washington’s ability to maintain this position. Relaxation of cannabis law in Washington and Colorado, as well as passive affirmation from the Obama administration, have reduced the U.S. capacity to play a leading role in global prohibition. Similarly, increasing calls for international drug policy reform can be heard from Central America and Europe. Subsequently, a void has been created in the prohibitionist movement, one which Russia is increasingly moving to occupy. Positioning itself at the head of a coalition of states, Russia seeks to continue the prohibitionist approach which has dominated international drug policy for the better part of a century.

A Century of US Leadership

The first steps towards a global drug policy were taken in 1909 at the Shanghai Opium Commission, the first ever meeting of international delegates to discuss the supply and trade of narcotics. Though the Commission itself proved relatively ineffective, it established the grounds for later international agreements such as the Hague Opium Convention of 1912.[1] It was this convention that formally introduced drug control as a legitimate component of international law. Later efforts built upon the successes of the Hague Opium Convention, culminating in the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the first international treaty to affirm a commitment to the prohibition of a broad spectrum of narcotics. Since then, prohibition has been the primary international policy for dealing with dangerous drugs.

Crucially, the United States has historically been the central advocate of global drug prohibition. In the early years of the twentieth century the United States pushed for prohibition whilst the colonial powers sought to continue profiting from drug cultivation in their overseas possessions. Following the adoption of global prohibition in 1961, the United States has frequently used development assistance as a tool to force drug producing states to adopt tougher measures against production and trafficking, most notably in Turkey in 1972. Subsequently, the U.S. was the first nation to declare a ‘war on drugs’ and to utilise the military in counternarcotic efforts, both of which are policies now adopted the world over.[2]

The End of Hegemony

However, the past decade has seen the United States’ role as the figurehead of global prohibition become compromised by the ongoing relaxation of domestic narcotics policy. Medical marijuana is currently available in twenty three states; legislators in both Washington and Colorado have legalised the production and sale of cannabis for recreational purposes. Similarly, lawmakers in Washington D.C. are currently considering a ballot on the legalisation of recreational cannabis. On a federal level, the Obama administration has chosen both not to take steps against state legislation -- despite prohibition being enshrined in federal law -- but has also made the decision not to pursue a policy of production prevention in Afghanistan. During NATO occupation, heroin production levels in Afghanistan have reportedly increased by a factor of forty.[3] These developments have inevitably undermined the United States’ role as enforcer of global prohibition.

Diverging Paths

International consensus is therefore becoming increasingly fractured as two diverging ideologies become increasingly apparent. On the one hand is the Western approach, coming from Europe, the United States and Central America. These states promote lenient policies such as the medical treatment of addiction, the decriminalisation of possession, and legalisation of drugs in certain cases. Opposing these measures is a group of countries including Iran, Japan, Indonesia, China and Singapore, who reject the trend of liberalisation in global drug policy.[4] Taking an increasing role at the head of these countries’ stance on drug policy is Russia. At the 2013 International Drug Enforcement Conference President Putin emphasised the necessity of combating ‘all kinds of drugs’, and asserted the liberalisation of global drug policy to be a ‘dangerous path’.[5] Meanwhile, the head of the Federal Drug Control Service of the Russian Federation, Viktor Ivanov, has described drug addiction as the ‘main stimulant of social and anthropological degradation of societies’ and condemned drug legalisation policies as an attempt to legalise ‘transnational organised crime’.[6]

The Russian approach to drugs policy therefore focuses on the security aspects of international trafficking, as opposed to the Western medical approach. Subsequently Russian policy maintains strong opposition to methadone treatment and harm reduction programs.[7] Russia has also repeatedly called for greater attempts by NATO to prevent heroin production in Afghanistan.

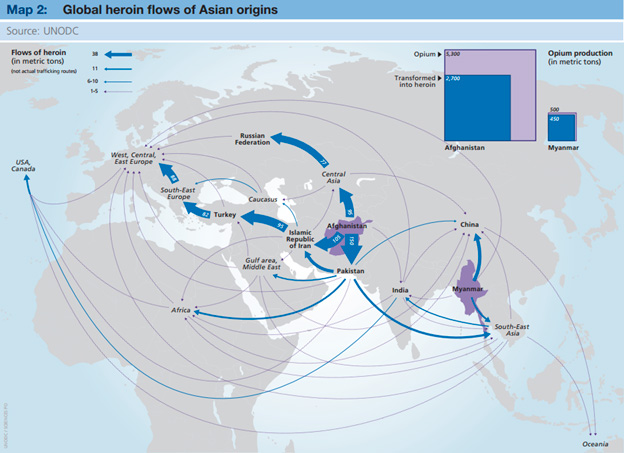

To a certain extent the dominance of security discourse in Russian drug policy is inevitable. Whereas Western European states may face social threats from drug trafficking, basic state security is never significantly threatened. In comparison, Russia shares a 7000 kilometer border with Central Asia, through which an estimated 95 tonnes of heroin leaves Afghanistan via the Northern Route. This inevitably has a significant destabilising effect on the region. Drug trafficking therefore poses a direct security threat to Russian borders in a way in which it does not to the West, and prohibition, which can be worse for addicts, has undeniably minimised drug trafficking. Opium production in 1906/7, for example, reached an estimated forty one thousand metric tonnes -- almost five times more than a century later -- at a time when the world population remained below two billion.[8] Iran, through which the largest amount of Afghan heroin is trafficked, adopts a similar stance to the Russian Federation.

Source: UNODC World Drug Report 2012

Domestic Contradictions

However, Russia’s increasingly hardline foreign policy stance could complicate its domestic drug abuse problems. Whilst there have been calls at the top levels of government to introduce harsher penalties for drug possession, currently punishments are relatively lenient.[9] This is a good thing. Russia maintains the highest level of injecting drug users in the world, and this, combined with opposition to harm reduction has helped contribute to a spiralling HIV epidemic.[10] Adopting the harsh measures in place in countries such as Indonesia and Iran, which see lengthy prison terms for possession, will merely lead to an explosion of prison populations and will not help addicts.[11] The optimum path for Russia must be to steer a middle ground between a no-tolerance policy for trafficking and a softer approach to tackle domestic drug addiction. Crucial to this will be engagement with Russia’s strategic partners, particularly its Central Asian and CSTO allies, in stemming the flow of heroin out of Afghanistan via the Northern Route.

A Divided Future?

Though Viktor Ivanov has argued that European liberalisation is incompatible with continued prohibition in Russia and the East, the decline of consensus on drug policy ultimately creates potential for the discovery of more effective approaches to drug trafficking and abuse.[12] Drug trafficking in states such as Russia and Iran poses a serious threat to regional stability in a way that it does not in Western Europe or the United States. The adoption of blanket drug policies therefore ignores the specific problems that regions face in combatting drug abuse. As approaches to drug policy increasingly diverge at an international level, what approaches will prove successful remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that current international attempts to curb and control the illegal drugs trade are both ineffective and in some cases, counterproductive; from this viewpoint, continued debate and new perspectives in combatting global drug trafficking must be understood as a positive step.

[2] http://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/wp-content/themes/gcdp_v1/pdf/Global_Com_Martin_Jelsma.pdf

[3] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sponsored/rbth/politics/7847007/Heroin-production-in-Afghanistan-has-grown-by-40-times-says-Russian-drugs-tsar.html

[4] http://www.politics.co.uk/blogs/2014/03/14/russia-has-replaced-america-as-the-world-s-drugs-policeman

[8] http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/this-day-in-history-the-shanghai-opium-commission-1909.html

[9] http://rt.com/politics/putin-drugs-punishment-distribution-831/; http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jun/08/russia-total-war-on-drugs;

[9]http://en.ria.ru/crime/20120319/172265311.html;

[9]http://rapsinews.com/legislation_mm/20111212/258831678.html

[10] http://en.rylkov-fond.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Lancet-OST-ARF-Russia.pdf; http://www.unodc.org/documents/regional/central-asia/Illicit%20Drug%20Trends%20Report_Russia.pdf