With the conversation surrounding U.S. president Trump recalling names like Shine, Cohn, and Browder, publications are buzzing up the meme that we're living in a new McCarthy era.

It is not surprising since McCarthyism is associated with the use of unfair allegations and investigations, smear campaigns, character assassinations and subterfuge that produces public fear and chaos.

One sees a lot of these things emanating from the Trump White House, among Democratic Party activists and others, sometimes regarding Russian efforts to influence U.S. politics.

But the political reality is that Russian and Soviet efforts to influence U.S. politics go beyond the likes of Alger Hiss and Harry Dexter White. Starting in 1937, Congressman Samuel Dickstein, a Democrat from New York City who played a key role in establishing the committee that would become the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) was outed in 1999 by authors Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev (based on Kremlin files) that Dickstein was a paid agent of the NKVD with the codename “Crook” (for good reason.)

But beyond all the sensationalism, what was the McCarthy era like when viewed from the perspective of a prominent Russian writer who watched it happen? After all, western media rarely examines McCarthyism from the Russian viewpoint.

This can be learnt from Vassily Aksyonov's, November, 1987 essay “Beatniks and Bolsheviks, rebels with (and without) a cause” which was published by The New Republic. Aksyonov notes that the Beats (or Beatniks as he calls them) were not a target of the McCarthy era because they were a loose-knit group who had no political orientation. More importantly, Aksyonov suggests that McCarthyism itself was small in scale when juxtaposed with the repression of the Stalin-era and the GULAG system in which he was forced to spend part of his youth.

“ It's not out of place to remind those who bring up McCarthyism that the senator's committee didn't destroy a hundredth of the number of lives that our "organs" put away in a single day.”

Why Aksyonov matters

Vassily Aksyonov was and remains one of the most controversial and popular Soviet era writers. His life, particularly the period of survival during the Stalin era, is noteworthy. It offers a sharp contrast to the likes of effete Western polemicists of his era, including such authors as Norman Mailer (left wing), and Norman Podhoretz (neoconservative).

Aksyonov was born to Pavel Aksyonov and Yevgenia Ginzburg in Kazan, USSR on August 20, 1932. His mother, Yevgenia Ginzburg, was a successful journalist and educator and his father, Pavel Aksyonov, had a high position in the Stalinist-era administration of Kazan. Both parents were prominent communists.

In 1937, however, both were arrested and tried for alleged connections to Trotskyists. They were both sent to GULAG and then to exile, and each served 18 years, but remarkably survived. Later, Yevgenia came to prominence as the author of a famous memoir, Into the Whirlwind, documenting the brutality of the Stalinist repression.

Aksyonov remained in Kazan with a nanny and grandmother until the NKVD arrested him as a son of “enemies of the people", and sent him to an orphanage without providing his family any information on his whereabouts.

Aksyonov lived at the orphanage until rescued in 1938 by an uncle, whose family he stayed with until his mother was released into exile. She had served 10 years of forced labor. In 1947, Vassily joined her in exile in the notorious Magadan, Kolyma prison area, where he graduated from high school.

His parents, noting that doctors had the best chance to survive in the camps, decided that Aksyonov should go into the medical profession. He subsequently entered the Kazan University and graduated in 1956 from the First Pavlov State Medical University in Leningrad (today St. Petersburg), and worked as a doctor for the next 3 years.

During his time as a medical student, he came under surveillance by the KGB, who began to prepare a file against him. It is likely that he would have been arrested had the liberalization that followed Stalin's death in 1953 not intervened.

A spokesman for the rebels of Soviet Russia's 1960s generation

Aksyonov has long been recognized as the leader of the Shestidesyatniki, the 1960s generation of writers, artists, and musicians who came of age in the Soviet Union during a brief period of relaxed ideological control known as the Khruschev-era Thaw. The work of the Beat movement writers (he calls them Beatniks) started having an impact on Soviet youth at that time.

Aksyonov published the first of many short stories in 1959, and a year later published his first novel, 'Kollegi' (1960; 'Colleagues'), which appeared in the popular magazine 'Yunost' (Youth), and became an instant bestseller. His second novel, 'Zvezdnyj bilet' (1961; 'A Ticket to the Stars'), was an even greater success. The novel's heroes are rebellious teenagers who defy traditional cultural values and adopt the unconventional behaviors of 'stylyagi' instead. Soviet youth obsessed with Western styles of dress, American jazz, Anglicisms, and slang.

Aksyonov's realistic novels brought him immense popularity among young readers, but his depiction of disaffected Soviet youth was controversial and provoked criticism by the authorities.

This was in sharp contrast to the Beat Generation that gained notoriety in the United States in the 1950s, who, Aksyonov claims later in this article, were apolitical and uninterested in political change.

In 1980, after co-editing the uncensored literary almanac “Metropol” and publishing it abroad, Aksyonov was stripped of his Soviet citizenship and forced into exile in the West. He worked for Radio Free Europe for a while and had the means to live as a bon-vivant, spending time in the casino-resort town of Biarritz, on the French-Spanish frontier, among other bon lieux.

In 1990, a year before the fall of the Soviet Union, Aksyonov's Soviet citizenship was surprisingly restored and his works once again became bestsellers in Russia. In 2004, he received the Russian Booker Prize, Russia's most prestigious literary award that is modeled on the English Man Booker Prize, for his novel “Volteryantsy i volteryanki” about Voltaire and Catherine the Great.

Aksyonov's analysis of the Beats (or “Beatniks” as he called them)

Those who study international literary movements will find it helpful to note how Aksyonov juxtaposes the beats with the Soviet literary scene of the post-World War II era (and the early 20th century revolutionary period) and Czarist and Soviet efforts to monitor and repress those cultural movements.

Aksyonov writes that...

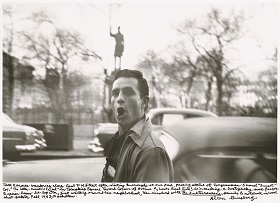

“By the beginning of the '60s, again from articles by various Soviet "Americanists and internationalists," we already knew the names of the San Francisco ringleaders: Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso. Their names sounded like pure silver to Westernizing Russian ears. In fact these writers really didn't have to write anything at all to go over big in Eastern Europe. I remember the girls of Bratislava in 1965 rolling their eyes and tossing their teased hairdos and sighing, "Oh, Gregory Corso." Little did they know that Gregory wasn't into girls.”

“Generally the American beatniks were older than us by a decade. They were closer to those Soviet writers who were called the “front-line soldiers”: Bondarev, Baklanov, Vinokurov, Fozhenyan. As far as I know, however, none of these American writers took part in the war; and so, when Ginsberg was in Moscow in 1964, he sought the company not of the front-line soldiers, but of our gang. He found it. We gladly hung out with him, because we were interested in finding out who exactly he was.”

Writer's note — Kerouac enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1942. Material released by the National Archives offers a dearth of personal information about Kerouac. Unable to complete basic training he spent a little over two months in a hospital under psychiatric observation and was found unfit for military service. He also tried to become a civilian sailor in the wartime U.S. Merchant Marine but quit after 3 months. You can access the full National Archive file on “John Louis Kerouac”.

“The manner of the 40-year old Ginsberg struck us as a strange manifestation of infantilism. His revelations (extravagant and constantly inebriated) seemed even more infantile, particularly when he began to attack his own CIA. Still, everybody liked him, maybe even because of his childishness, his gabbing about drugs, his Indian chants. In short, he didn't make an outstanding impression on anyone, and was overshadowed by the "giant" Yevtushenko. We were quite surprised to learn of his incredible success in Prague, where crowds of youngsters trailed him and he was chosen king of the spring holiday.”

“Kerouac is too wild for American neoconservatives and for Soviet commissars. He believed that only people outside the system can be considered alive: the loafers, the cheats, the bag people, the prostitutes, and those who were lucky enough to be born with dark skin. In a passage from On the Road Kerouac glorifies the “mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow Roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.”

Aksyonov examines “Beatniks” influence during Khruschev “thaw”

“In the stream of insults that Nikita Khrushchev brought down upon us in the winter of 1963, the American word "beatnik" constantly popped up. It's not out of the question that this word attracted the leader's attention because of its somewhat Russian sound. It would be difficult to imagine the leader of progressive mankind insulting young writers and artists with the word “existentialist.” Much more likely that he would choose “beatnik”.

Writer's note — The word “beatnik” is attributed to the legendary San Francisco newspaper columnist Herb Caen, who, in 1957 after launch of Sputnik and the start of the “space race” combined the idea of the loose lifestyle of the Beat writers with the Russian “nik” to suggest that these folk were different, alien to contemporary American society. It took nearly a decade for the tag “beatnik” to become politically incorrect. Today the designation “beatnik” is considered a cultural taboo and frowned upon. It's common to refer to them as “The Beats” or “The Beat Generation.”

“That is how the Boss (Khruschev) envisioned the army of beatnik-revisionists. Where did this word come from? Who were these beatniks? In 1963, we, meaning those branded with this label, didn't understand it very clearly. It's not inconceivable that Khrushchev knew better who the beatniks were: he had an entire staff of researchers who had access to Western literature. We didn't have a clue. Information gleaned from Soviet magazines was fragmented, although it was carefully amassed, as was everything Western. In the magazine Foreign Literature somebody wrote something about James Dean and his movie Rebel Without A Cause, to the effect that he was rebelling against bourgeois morality. In the same magazine, or maybe it was in In Defense of Peace, mention was made of certain coffeehouses in San Francisco where youngsters in denim (the word ‘jeans” didn't exist yet) would get together, listen to jazz, read scandalous poetry.”

Writer's note — Aksyonov speaks of San Francisco. But prior to San Francisco the crowd that became “the Beats” was initially active in New York during the early-mid1940s, around Columbia University and Times Square, and during the 1950s the bohemian atmosphere of Grenwich Village, near the docks on the lower West Side of Manhattan, and some haunts in the East Village being their favorite venues.

“The official Soviet view of the American beatniks was very amusing. They were sort of OK, on the one hand, as shakers of the foundations of bourgeois society, and as promoters of our cause. On the other hand, they expressed merely a petit bourgeois protest, that is, they didn't promote our cause enough, they even distracted youngsters from the social struggle. In any event, at least some grains of their work began to appear in the Soviet press at the time of the "first thaw" in 1962.”

Aksyonov viewed Kerouac's work as formless, disconnected, politically naïve

“Of course, Kerouac produced not literary works, strictly speaking, but highly charged, narcissistic monologues of the type that Ginsberg came to call "spontaneous prasads (offerings, translated from Hindu) of bop." They were formless and disconnected, and should be judged not from the standpoint of literary merit but socially, as the expression of a rebellious generation.”

“What kind of horrors of war did the American beatniks experience if none of them served in the army, if none took part in military action against Germany and Japan? The majority of those listed in the Russian group also did not participate in any military action, with the exception of Okudzhava and Neizvestny. But we did experience bombings, evacuations, starvation.”

“I doubt that the American beatniks experienced even an interruption in their supply of Coca-Cola. One more point about World War II: despite its horrors, it was a source of great inspiration for Russians. The war brought a feeling of spiritual community to Soviet people for the first time, an understanding that people could unite not only out of common fear but also in a struggle for human dignity.”

“The real horror that our generation experienced came not in the form of the war, but in the form of Stalinism. Parents or close relatives of all the above-mentioned Russians went through torture chambers, prisons, or camps. Overcoming that terror is what fundamentally distinguishes us from our American counterparts.”

“The American beatniks were not exposed to the same level of repression that we were; some of us, myself included, were forced out of our own country.”

“We felt a certain closeness to these people who had given their establishment the finger, because we wanted to do the same to our establishment. But just as their establishment was different from ours, so was our giving it the finger.”

“The problems that the American beatniks grappled with in the 1950s had been addressed by the young geniuses of Russia's Silver Age in the 1910s. The Americans' search for open forms was a forward movement, but for us that search was in many ways a backward movement, to the smothered but not completely annihilated Russian avant-garde.”

“The American beatniks had a revolutionary position and tried to break a specific tie. Although our "wave" did break with socialist realism, we did it with such disdain that we didn't consider it much of a break; our main concern, the pathos of our movement, was the restoration of a tie, the attempt to mend the broken chain of our avant-garde tradition.”

“The deliberate departure from politically significant themes: that is what finally distinguished our development from the beatniks'. Needless to say, all Western types of liberation struck us as whimsy; but we shunned our own democratic movement too, which gave rise to talk about our own conformity. Only later, when the repression gained strength, was there a schism among us: some of the New Wave joined the domestic rights campaign, others supported Western pacifism and blamed the West for the neutron bomb. Imagine the courage required for that!”

Considering the body of his work, not much of Aksyonov's writing has been translated into English. Looking forward, one can only wonder how translations of Aksyonov's work to English might improve the cultural understanding between Russian and Americans (and other users of English) at this difficult juncture.

General Background References

- Biographical material on Aksyonov featured in this article is all open source information, from Wikipedia, Encyclopedia Britannica and Amazon.com.

- Article by Vassily Aksyonov “Beatniks and Bolsheviks” published in New Republic 1987.

- https://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-ehrmann/kerouac-on-the-road_b_1552171.html.

- https://www.amazon.com/Rolling-Stone-Book-Beats-Generation/dp/0786864265

- Firing Line television program — William F. Buckley, Jr. discusses beatniks and hippies with Jack Kerouac and others.

- Television program “Rebels, A Journey Underground #2, A New Kind of Bohemian” featuring Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac, others.

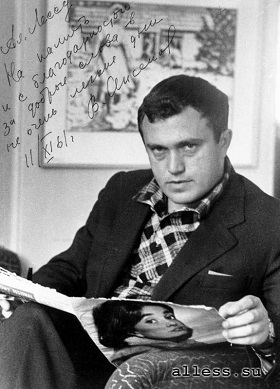

- Photo and bio of Vassily Aksyonov via RT.