Yemen: Following in Afghanistan’s Footsteps?

Followers of the Houthi movement raise their

rifles as they shout slogans against the Saudi-

led air strikes in Sanaa April 5, 2015

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

General and Russian History Department of the Higher School of Economics

After Ali Abdullah Saleh stepped down as President of Yemen, Vice President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi became President, winning the presidential election on February 21, 2012, in which he was the sole candidate. Later the National Dialogue Conference (NCD) was convened to draft a new constitution. The country entered a period of change, which was due to end by the beginning of 2014.

After Ali Abdullah Saleh stepped down as President of Yemen, Vice President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi became President, winning the presidential election on February 21, 2012, in which he was the sole candidate. Later the National Dialogue Conference (NCD) was convened to draft a new constitution. The country entered a period of change, which was due to end by the beginning of 2014.

View from the inside

Mansur Hadi failed to act as an impartial arbitrator and to ensure the effective work of the NCD. The success of Ali Saleh’s rule, which lasted for 33 years, was largely due to his skillful maneuvering among the interests of different tribes. As such, the president protected the existing status quo and managed to remain above the fray. Hadi has failed in doing the same.

As a weak political figure, he almost immediately allowed the al-Ahmar family to pull the blanket over to its side, which eventually knocked the political bottom out from under the influential family, and then the president himself. During its reign, the al-Ahmar family clearly strengthened its position in power and ignored the interests of other political forces, be it southerners, residents of Taiz, northerners or representatives of Saleh’s environment. As a result, by the beginning of January 2014, the National Dialogue Conference (NCD) fell apart, and the country faced increasing discontent with the dominance of power held by the al-Ahmar family and affiliated Islamist organizations (the Al-Islah Party, the Yemeni Muslim Brotherhood branch and the Salafi al-Nusra).

By the beginning of January 2014, the National Dialogue Conference (NCD) fell apart, and the country faced increasing discontent with the dominance of power held by the al-Ahmar family and affiliated Islamist organizations.

Therefore, the gradual monopolization of power in Yemen by the al-Ahmar family put its opponents on the same side of the barricade and forced them to take extreme measures. This was the starting point for the shaping of the Huthi-Saleh alliance, which later became the dominant force in northern Yemen.

It is quite clear that the prospects of the al-Ahmars staying in power encountered an absolute rejection by the Huthis, the NCD as well as the southerners. This predetermined the revolution of September 21, after which the al-Ahmars were forced to leave the country, while the Ansar Allah movement, having forged alliances with Yemeni tribes and NCD members, actually established control over northern Yemen.

The situation that developed has been typical for the northern Zaidi tribes of Yemen. It is much more beneficial for the Hashid tribes to recognize the authority of Abdel-Malek al-Houthi who does not belong to tribal figures, but enjoys considerable support among faithful Muslims, than respect the authority of Sadiq al Ahmar or Ali Saleh, the relationship with whom would incur significant reputational losses for the tribes of Northern Yemen.

Xinhua/Mohammed Mohammed

Yemeni ex-president Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi

attending the military parade. May 22, 2012

Every day Hadi remained in power aggravated the situation in Yemen, and the number of people dissatisfied with his rule was constantly increasing. In this regard, it is not surprising that the former president, supported by Saudi Arabia and fleeing to Aden, tried to weaken the northern territories. It is not accidental that at the beginning of March 2015, he called on the leaders of Taiz and Ibb governorates to recognize him as the legitimate president of Yemen and to provide military assistance. Although the latter refused to comply with the request, Hadi’s strategy was not unfounded, since these two provinces had historically been the regions with the least loyal and developed tribal structures in northern Yemen.

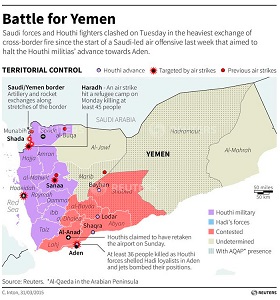

Following the refusal of the Aden garrison command to obey Hadi, the president, left without military protection, took an unexpected decision to apply for help to the leaders of the Abyan governorate. On the one hand, it was obvious that Hadi had no choice. The situation was only getting worse. First, the proposal to relocate Yemen’s National Dialogue to some place outside the country (in particular, Riyadh, Doha and Muscat were suggested) antagonized northerners who found this proposal unacceptable, and then Hadi’s request for military intervention in Yemen left him without southerners’ support once and for all. It’s not surprising that on March 24, 2015, the very day when the president called on the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf to intervene, the northerners moved into the province of al-Lahij practically unhindered. It took them just several hours to capture Aden with its population of six hundred thousand, which clearly illustrates Hadi’s lack of serious support even in the south of the country. Moreover, the Al-Islah Party that previously was in sympathy with Hadi’s ideas criticized the actions of the northern neighbor the day after the Saudi air strikes.

Hadi is a political corpse, doomed to an ignominious end.

As a result, Hadi has entered the world history as the president who managed to lose power twice. As of today, neither Saudi airstrikes nor even ground operations are able to bring him back to life. Hadi is a political corpse, doomed to an ignominious end. He is the President without any chance of returning to Yemen as the victor.

View from the outside

During the last several years, Riyadh has systematically nursed the interreligious conflict in Yemen. It is not without reason that the Arab media shapes the conflict in Yemen as a fight between the Shiites and the Sunnis, which, in turn, is associated with the Iranian-Saudi confrontation. It is under this pretext that the Arabs have united against a common enemy, namely Iran, beginning a campaign of mopping-up the pro-Iranian elements in Yemen. A particular emphasis has put on the fact that in 2014-2015, the Shiites captured power in Yemen, overthrowing the legitimate President Mansur Hadi.

However, this kind of reasoning is far from reality. Power in northern Yemen, populated by the Zaidis, has always belonged to the Shia. This was so in the days of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, under General Abdullah al-Sallal, under Abdul Rahman al-Aryani, as well as under Ali Abdullah Saleh. That is why the establishment of Huthis’ control over most of northern Yemen has not changed the confessional map of the country.

It is the danger that Iran may place Yemen in its sphere of influence, which is being instilled in the minds of Arabs, that has forced Arab states to take up the pro-Saudi position concerning Yemen. In this regard, the situation in Yemen threatens to escalate another round of the Arab-Iranian conflict. Saudi Arabia's also tries to consolidate the international community in an attempt to exert pressure on the Huthis, who are regarded by the international community as rebels, insurgents and militants. Not accidentally, Riyadh in recent months has repeatedly emphasized the legitimacy of the government and the presidency of Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi. This explains why Arab countries have started to move their diplomatic missions from Sana'a to Aden, recognizing the latter as the new capital of the Republic of Yemen.

South Yemen poses no such threat to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as the North does due to the unresolved territorial dispute involving Najran. Second, the political spectrum of forces in the south is quite diverse, which is to the advantage of Riyadh, accustomed to playing upon the internal conflicts.

At the same time, by supporting the southerners, Saudi Arabia has clearly set the goal of weakening northern Yemen. First, South Yemen poses no such threat to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as the North does due to the unresolved territorial dispute involving Najran. Second, the political spectrum of forces in the south is quite diverse, which is to the advantage of Riyadh, accustomed to playing upon the internal conflicts. The situation in the south is completely different from the one in the northern part of the country, which is dominated today by two key political forces, namely Ansar Allah and the NDC. Establishing a dialogue with them appears quite problematic for the Al Saud family. Finally, the north of Yemen has always been characterized by developed tribal structures and underdeveloped state institutions, in contrast to the south, where the situation is just the opposite. This, in turn, has predetermined the superiority of the North over the South in military terms.

Saudi Arabia has already taken its first step to strengthen its influence in Yemen by carrying out air strikes on its territory. A stake has been placed on provoking a civil conflict in Yemen itself, while the key role has been assigned to the ISIL and separatist movements in the south, such as Al-Hirak. This tactic has been used by Saudis before: during the civil war in 1994, Riyadh supported the separatist movement of the socialist south to weaken the north, which the royal court regarded as a permanent threat.

It’s a different matter that the air raids on Yemen are not producing the desired effect, which is illustrated by the speeches at the Arab League Summit in Sharm el-Sheikh. The willingness of a number of Arab countries to begin a ground operation in Yemen raises many questions as well. First, Arab solidarity with Saudi Arabia is too thin. One of the key countries of the Arabian Peninsula – Oman – rides the fence, which has always been characteristic of Sultan Qaboos, a Muslin of Ibadi denomination, who for many years has been a mediator between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

In addition, Sudanese President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, who faces a very shaky political situation and clearly is not interested in becoming involved in a new regional war, just gave formal consent to participate in the anti-Yemen coalition. The same can be said about a number of Arab countries from Morocco to Jordan. Therefore, the formation of the Arab coalition against Yemen on paper does not mean practical steps towards its creation. Moreover, the experience of pan-Arab forces in the struggle against Israel or Iran leaves much to be desired.

Secondly, carrying out a ground operation in Yemen is fraught with the possibility of escalation into a protracted and exhausting war for all the parties to the conflict, which will require a lot of resources, including human lives. At the same time, participation in a protracted conflict in Yemen can deliver a blow to the aggressor countries themselves, especially Saudi Arabia and Egypt, which today are facing an extremely hostile environment. On their northern outskirts, the Islamic State carries out its operations and will sooner or later focus its expansionist policy on the southern vector. The east has traditionally been a volatile region due to the Shiite population residing in the Eastern Province, and the Bahraini crisis can aggravate the situation further. If the control of the south is lost, events may develop unpredictably. This is particularly so amidst the political situation in Saudi Arabia, which is becoming increasingly reminiscent of the ruling elite crisis in the USSR in the 1980s. In the foreseeable future, this crisis will only intensify due to the looming generational change of the political elite and the exacerbation of the struggle for power. As for Egypt, the threat from the Islamic State in the east is multiplied by the one from Libya and internal instability in the Sinai Peninsula, coupled with pro-Ikhwan sentiments in the Egyptian provinces.

Secondly, carrying out a ground operation in Yemen is fraught with the possibility of escalation into a protracted and exhausting war for all the parties to the conflict, which will require a lot of resources, including human lives.

Another threat comes from al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) that has recently sworn allegiance to the Islamic State and taken responsibility for the mosque bombings on March 20, 2015 in Sana'a, which killed more than 150 people, mostly Huthis.

After Ali Saleh’s resignation in 2011, AQAP dramatically stepped up its activities, particularly in the oil-rich province of Ma’rib, which, in turn, was due to both external and internal factors. The former implies the emergence of the Islamic state and its growing influence in the Middle East. This successful project could not but affect the overall situation in the region: various radical Islamist groups have perceived ISIL as the real force worth joining. AQAP has been no exception and received an additional motivation for its development. The internal prerequisites for AQAP intensified activity primarily include an aggravated socio-political situation in the country, which is a breeding ground for groups like ISIL striving to realize their goals. The growing influence of Huthis in Yemen, who are incompatible with al-Qaeda on the existential level, is another important prerequisite.

Using AQAP in his interests, primarily to neutralize the Huthis, Mansur Hadi, guided by Riyadh, risks twisting the knife and turning Yemen into a second Afghanistan, making the country the next springboard for the further entrenchment of the Islamic State

What is more, Hadi’s connection with AQAP is not an assumed concern at all. Aware of the traditional military advantage of the north over the south, which was only strengthened by Ali Saleh’s demilitarization reforms in southern provinces after 1994, as well as of the disobedience of most of the army to Defense Minister al-Subaihi’s orders, Hadi fled to Aden and tried to win the support of tribal sheikhs. Having failed to gain the backing of the leaders of Taiz and Ibb governorates in early March 2015, the former president asked for help from the sheikhs of Abyan province, which had been the stronghold of AQAP in recent years.

Suicide bombings at mosques in Sana’a on March 20, 2015 became the starting point of the military offensive against Aden. The fact is that responsibility for the bombings was taken by ISIL, in particular, by Jalal Bal’idi, a senior AQAP official and a native of Shabwah governorate, whom Mansur Hadi hosted on March 23, 2015, and by Abd al-Latif al-Qadi, a native of al-Mudia tribe in Abyan province, the home province of Mansur Hadi. In addition, on March 20, a suicide bomber was neutralized at a mosque in the town of Sa’ada, who just as in the case of explosions in Sana'a, entered the mosque disguised a crippled citizen, hiding explosives in his cast,and joined the first rows where the Ansar Allah senior officials were. Interestingly, a few minutes before the expected explosion, the Al Arabiya channel reported the terrorist attack in Sa'ada as a fait accompli, indicating the mosque in which it had happened, therefore allowing authorities to figure out who the suicide bomber was.

The danger here is that using AQAP in his interests, primarily to neutralize the Huthis, Mansur Hadi, guided by Riyadh, risks twisting the knife and turning Yemen into a second Afghanistan, making the country the next springboard for the further entrenchment of the Islamic State.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |