The snowballing development of space-based weapons and looming militarization of space, although hardly imminent, pose a relatively new problem for Asia-Pacific, where there is real development potential that could, someday, make a surprise breakthrough.

There are several reasons to pay close attention to China’s space program and especially its military component. First, China is the region's biggest country, and boasts one of the world’s most secretive programs in this area, that is thought to involve numerous military and dual-use projects. Information is scant, what there is largely comes from sparse information in the Chinese and Western media sourced to military and intelligence leaks, whistle-blowing bloggers, scientific journals and circumstantial evidence such as observations made by Russian and American astrophysicists, geophysicists and other scientists. Second, China is the only state in the region to have territorial disputes and smoldering conflicts with practically all its neighbors. Third, Beijing's foreign policy is rising to a qualitatively new level after Xi Jinping announced the policy of "the great nation revival" and "the Chinese dream", and the country accumulated huge resources for a society that now demands increased involvement in the world arena.

Facts and Figures

In its report to Congress on China's military power in 2013 [1], the U.S. Department of Defense outlined systems and technologies related to space weapons. Larry Wortzel [2] classifies China’s projects as follows: 1) satellite jamming, 2) space object collisions, 3) kinetic weapons, 4) space-to-surface weapons, 5) aerospace vehicles operable in the atmosphere’s upper layers and in outer space, 6) laser weapons, 7) microwave weapons, 8) beam weapons, 9) electromagnetic weapons, 10) technologies to disguise attacks from enemy spy tracking satellites that use heat and other missile emissions.

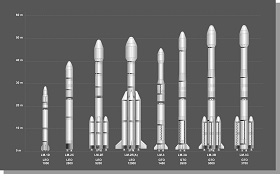

As for facts and concrete examples, data is available on the Chinese program for eight earth-orbiting military-adaptable infrared-vision satellites, the Baidu space navigation system, emerging technology for identification of enemy satellites [3], and 16 Yaogan remote sensing satellites that can be used in resource surveys and as part of disaster warning systems, but can also be used to gather data on military forces and infrastructure on the Earth’s surface. China also deploys the Tianhui (2), Huantsan (3) and Jiayun satellites for stereocartography, surveying land resources and monitoring weather systems; the Hayan satellites for ocean monitoring; and Fengyun meteorological satellites [4]. In 2014, Beijing launched the one-meter resolution Gaofeng-2 satellite to optically probe the Earth [5]. Finally, China is known to have started manufacturing the new LM-5 modification to deliver extra-heavy cargoes [6].

Satellites can also be used to create conditions for collisions or orbit changes of enemy vehicles. In 2010, Russian and U.S. military experts twice saw intentional and very close maneuvering of Chinese satellites SJ-06F and SJ-12 in the near-earth orbit, to highly precise coordinates, suggesting the exercise was either practice for orbital shifting or was aimed at carrying out close proximity reconnaissance.

In 2013, the Chinese used their LM-4C rocket to launch three small satellites (Chuangxin-3, Shiyan-7 and Shijian-15), which also started atypical maneuvering in relation to each other, with one of them changing course and passing in front of the other at a mere 100 meters. The Shijian-15 is equipped with a telescopic arm able that can capture or damage other objects.

China is known to have developed laser, microwave and beam anti-satellite weapons [7]. Its work on laser systems began back in the 1960s, but was later suspended and only resumed in the 1980s-1990s (http://www.militaryaerospace.com/news/2014/08/02/space-invaders-china-s-space-warfare-capabilities.html), and was followed by repeated tests over the past decade (1, 2).

According to the U.S. consultancy IHS, China has been working to develop anti-satellite missile systems since the 1960s [8], it suspended the program in the 1980s and resumed it in the 1990s. Non-target tests on anti-satellite kinetic weapons began in 2005 and 2006 during the maiden launches of the SC-19 rocket. In 2007, the Chinese destroyed their old meteorological satellite with a kinetic kill vehicle, leaving a massive amount of debris, in order to officially demonstrate its anti-satellite systems capacity. The follow-up tests in 2010 and 2013 were presented as missile defense trials. In May 2013, the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics spotted the 10,000-km-high launch of an anti-satellite missile from the Xichang Center, while Beijing called it a probe for magnetic filed research. The American Secure World Foundation performed an analysis establishing that it might have been "a test of the rocket component of a new direct ascent ASAT weapons system derived from a road-mobile ballistic missile. The system appears to be designed to place a kinetic kill vehicle on a trajectory to deep space that could reach medium earth orbit, highly elliptical orbit, and geostationary Earth orbit". In July 2014, China launched another ballistic missile capable of killing space targets, unnerving the United States.

Beijing is also engaged in developing a spaceplane, i.e. an air- and outer space-capable, high-speed, maneuverable, long-range and undetectable vehicle intended to "surpass the existing analogs in aerodynamics and functionality". In 2006, the world learned about spaceplane programs that are to be completed by 2020. One involves the construction of a 120-ton shuttle-type spaceplane LM-SLV with a carrying capacity of up to seven-tons. The vehicle seems designed for the delivery of general-purpose and military cargos to a future Chinese orbital station. The second project appears to be aimed at developing a 100-ton unmanned spaceplane. In 2007, reports emerged about tests on the Shenlong small spaceplane, while at the Paris Le Bourget air show in 2013, a top Chinese aerospace official confirmed that China "was going ahead with the development of a spaceplane".

People have been speculating about China’s mysterious lunar program and plans for a Moon station. In 2014, Beijing started preparations to launch a recoverable lunar orbital module. In May 2014, the Renmin Ribao newspaper reported the completion of a test program for an experimental land-based complex simulating a future Chinese Moon station, as three crewmen spent 105 days in a closed-circuit life support system. However, the dates for the construction of the lunar base have yet to be revealed, as has its purpose.

China’s plans for an orbital station are also of particular importance. Virtually nothing is known about this project, other than the fact that the completion date has been set at 2020. The complex is to be based on the Tiangong-3 module. But questions still remain, such as China's commitment to international rules, its openness or the limits for interaction with the International Space Station.

According to a 2007 publication by the American Enterprise Institute’s Dr. Wortzel, who has met many Chinese military leaders and analysts and analyzed numerous publications and restricted databases, the PLA has specialized units working on space-surface kinetic weapons, which seems quite a troubling development.

The Public is Pro

As far as the attitudes of the Chinese authorities and public are concerned, the following main trends and features are apparent.

First, the space weapons buildup is a calculated policy, as Beijing is well aware of its power to boldly declare its achievements in supreme space weaponry. The 2008 China Defense White Paper insists on the priority of "building up assets for maritime and space security". In the November 2009 interview to Jiefangjun Bao, the PLA daily, the then Air Force Commander Xu Qiliang said: "International competition is entering the open space… This is a historical inevitability and an irreversible process". Later he was appointed Vice Chairman of Central Military Commission and became de facto the second most senior official in the People's Liberation Army. A 2011 report to the All-China Assembly of People's Representatives said that people "are to implement innovative industrial projects including… space infrastructure", while similar ideas were aired at the 18th Congress of the CPC by Hu Jintao, China's president 2003-2013.

Second, Chinese military space intentions are clear and boil down to defending national borders against a backdrop of simmering territorial disputes, active combat within a non-contact war, and access to resources.

The third objective remains theoretical, although Western analysts, such as those at Stratfor, suggest that China may seek to develop rare minerals present on asteroids, the Moon and Mars. In 2011, Tsinghua University scientists reportedly pondered changing asteroid paths to bring them toward the Earth’s orbit. Judging by Xu Qiliang's statement, the second objective appears quite feasible, while implementing the first would, even now, be fraught with threats to stability in the broader Asia-Pacific region. Beijing is engaged in numerous territorial and maritime disputes and considers certain foreign spaces as common, as is the case with the South China Sea, and also claims an active role in the Arctic Council.

Beijing's approach, fairly belligerent public sentiments and serious grounds for space militarization voiced by defense and scientific communities (a series of papers forming a sort of national space war doctrine has been produced by Larry Wortzel do reflect the China’s overall foreign policy ambitions as formulated by Xi Jinping. After the 18th CPC Congress, he called for the "construction of potent digitized strategic missile forces" [9]. Closing the All-China Assembly in March 2013 that elected him Chairman of the PRC, Mr. Xi stated that "while advancing along a peaceful path", the army must be ready to "implement the party decisions, win wars and create a strong army".

Public opinion is clearly reflected by Chinese media, such as a harsh editorial of January 6, 2013 in the newspaper Huanqiu Shibao about the Western response to possible Chinese anti-satellite weapons tests [10]. The article was highly praised in confrontational and even insulting and nationalist Internet commentaries aimed at neighbor states and the West. Other media eagerly follow suit, and the Xianggang Zhounpinshe, for example, instead of rebuffing allegations that space weapons have been tested, enthusiastically states that China is growing into a space power.

Consequences for Asia-Pacific

However, the broad-based and rapid advance of Chinese space weapons could shatter the rickety regional balance. Other countries face numerous risks of premeditated or accidental destruction of their vehicles, damage from falling rockets or missiles, and the risk of being drawn into an arms race, as grounds emerge for others to take the same line. In 2012, the need for anti-satellite space weapons and military mini-satellites was voiced by the Indian Defense Research and Development Organization, whereas in summer 2014, Japanese media announced plans to establish a "specialized space unit within the national self-defense forces to monitor the near-earth orbit" [11]. The North Korean space program [12] is well-known, while South Korea plans to launch its first rocket in 2019 [13], but has ample resources to advance missile defense through extensive defense cooperation with the United States and Japan [14] and, consequently, to create anti-satellite missiles at least.

The next in terms of military space efforts seem to be the Southwest Asian countries, which are to varying degrees hostile to China. Outer space programs are underway in Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia, with the problem exacerbated by growing anti-Chinese sentiments generated in part by Beijing's territorial claims.

* * *

Security in the Asia-Pacific region is extremely fragile and could be shattered by a minor irritant, and the rapid and practically unrestricted development of China’s space weapons may trigger a dangerous spiraling of tensions, sparking a chain reaction involving region-wide militarization.

The situation could be reversed by regular contacts between countries for discussions on relevant issues, mutual notification and control by relevant bodies, and the active involvement of scientists in space militarization issues relating to both regional and global developments. But the key seems to lie in producing international law documents prohibiting the militarization of space. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 bans "the establishment of military bases, installations and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapons and the conduct of military maneuvers" only "on celestial bodies." The deployment of WMD on orbital and celestial bodies is also prohibited, while surface-to-space weapons are not mentioned. These documents could work if they contained a detailed ban on specified weapons and technologies or referred to all classes of space weapons, i.e. surface-to-space, space-to-space, and space-to-surface. Such measures should definitely promote a peaceful, equal and meaningful dialogue for the entire region.

Regretfully, the likeliest scenario seems to be the continued Chinese buildup of space and other weapons, and therefore the greater risk of the continued militarization of space. Since other Asia-Pacific leaders have already undertaken military space efforts, tensions would also grow, with only a major incident or engagement of international institutions present as the possible levers that could turn the situation around.

1. According to the report, space weapons include reconnaissance and monitoring satellites officially intended to support the operation of navigation, communications and meteorological systems and that can perform defense functions; high-capacity space rockets; disguise technologies; and anti-satellite weapons.

2. Larry Wortzel is a veteran of military intelligence and U.S. Pacific Command, U.S. Military Attaché in Beijing in 1995-1997, former Director of Asian Studies Center at the Heritage Foundation, member of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission of the United States Congress.

3. Office of the Secretary of Defense. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2010. Р. 25, 36. URL: http://www.defense.gov/pubs/pdfs/2010_CMPR_Final.pdf

4. Office of the Secretary of Defense. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2013. Р. 65.

5. Satellite for Sensing Earth Surface Launched // ITAR-TASS Asia Bulletin. August 20, 2014.

6. Office of the Secretary of Defense. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2013. Р. 9.

7. Office of the Secretary of Defense. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2010. Р. 36.

8. IHS is a leading U.S. consultancy covering defense issues.

9. Xi Jinping Meets PLA Servicemen // ITAR-TASS Asia Bulletin. December 7, 2012.

10. The article "Satellite Test Sparks Overblown Worries" suggests that "China must be able to attack American satellites", "China should continue developing anti-satellite weapons and evade the debate on peaceful use of outer space thorough the missile defense cover", "until China-U.S. relationship remains strategically uncertain, China should expediently obtain a space-based trump card", "China is eager to advance along a peaceful path and have means for strategic containment in disputes and conflicts… and for strategic retaliation." In the end, the newspaper sounds convincingly metaphorical by saying that it hopes that "all Western allegations about Chinese anti-satellite weapons tests were true."

11. Self-Defense Builds Space Force // ITAR-TASS Asia Bulletin. August 4, 2014.

12. Journalists Visit Space Center // ITAR-TASS Asia Bulletin. April 9, 2012.

13. Satellite Launch Expected // ITAR-TASS Asia Bulletin. August 22, 2-13.

14. Republic of Korea: Missile Defense Plans // ITAR-TASS Asia Bulletin. February 15, 2013; Military Treaty with Japan Signed // ITAR-TASS Asia Bulletin. June 29, 2012.