Who Sends Peacekeepers and How?

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Professor, Doctor of Law; president of the Chair of International Law at the People’s Friendship University of Russia; member of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

PhD fellow at the Chair of International Law, PFUR Law School

The International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers is celebrated on 29 May. The day has a dual purpose – to commemorate UN peacekeepers who have died in the name of peace and pay tribute to all men and women dedicating high levels of professionalism, dedication and courage by having served, or currently serving, in various UN peacekeeping units. With the world facing new challenges, UN peacekeeping is evolving. How are peacekeeping missions established? Who funds them? How are they composed? Do regional institutions contribute to them? What is Russia’s role? What is the future of peacekeeping?

The International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers is celebrated on 29 May [1]. The day has a dual purpose – to commemorate UN peacekeepers who have died in the name of peace and pay tribute to all men and women dedicating high levels of professionalism, dedication and courage by having served, or currently serving, in various UN peacekeeping units. With the world facing new challenges, UN peacekeeping is evolving. How are peacekeeping missions established? Who funds them? How are they composed? Do regional institutions contribute to them? What is Russia’s role? What is the future of peacekeeping?

UN Peacekeeping’s Decision-Making

1. What is peacekeeping?

The United Nations (UN) launched its first peacekeeping operations in 1948 when the UN Truce Supervision Organisation was established to monitor the Armistice Agreement in the Middle East. Since then, 69 peacekeeping operations have been conducted [2]. Over that time, hundreds of thousands of soldiers, tens of thousands of policemen and other UN civilian staff from more than 120 countries of the world have contributed to UN peacekeeping [3]. Over 3,200 UN peacekeepers from 120 countries have died performing their duty under the UN flag [4].

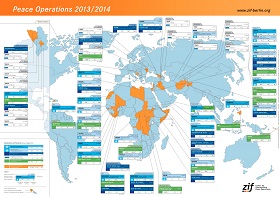

Thanks to the flexibility of the peacekeeping component, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, peacekeeping forces were deployed in a range of different configurations. As of 10 April 2014, 16 peacekeeping missions are ongoing (in India, Pakistan, Haiti, Abyei, Darfur, Congo, Western Sahara, Cote-d’Ivoire, Liberia, South Sudan, the Golan Heights, Lebanon, Cyprus, Kosovo, Mali, Central African Republic and in the Middle East), as well as one special political mission in Afghanistan [5].

Peacekeeping is one of the most effective instruments available to the UN to offer help to the host countries going through the difficult time of a post-conflict situation. During its peacekeeping operations, the UN is governed by three key principles: consent of the parties; impartiality; and non-use of force except in self-defence or to enforce the mandate.

2. Legal Framework and Role of the UN Security Council

Although there are no explicit provisions on peacekeeping in it, peacekeeping operations have traditionally invoked the UN Charter. In accordance with the UN Charter, the Security Council is vested with the primary responsibility for maintaining peace and security. Under Article 25 of the UN Charter, all member states agree to submit to Security Council resolutions and are bound to honour them. It therefore follows – and is recognized by the majority of the states – that the resolutions to establish, conduct, amend, expand, extend or wind up peacekeeping operations, as well as to determine their place and time, are part of the Security Council’s jurisdiction. The Security Council does not have to refer to any specific chapter of the UN Charter in its resolutions authorizing the deployment of a peacekeeping operation. In recent years, when passing its resolutions to authorize peacekeeping missions in difficult, post-conflict situations, where the host country is not in a position to safeguard security and public order, the Security Council tends to invoke Chapter VII of the UN Charter that refers to “Action with respect to threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, and acts of aggression” [6].

The decision to start a new mission is taken after certain requisite steps have been made. As the conflict evolves and grows, or a process of settlement develops, the UN tends to start with a series of preliminary consultations in order to select the best suited response measures on the part of the international community. Such consultations usually involve the following parties: all UN stakeholders (UN member states; UN agencies, programmes and facilities); the potential host country’s government and parties on the ground; member states, including those that could contribute army and police personnel to the peacekeeping mission; regional and other intergovernmental agencies; and other key external partners.

The Security Council (“SC”) implements its measures in the context of the crisis situation on a case by case basis. In resolving to deploy a peacekeeping mission, the SC has to take into account a number of factors, including the following: is the ceasefire agreement being complied with and are the parties prepared to seek a political settlement as part of the peace process; is there a clear political goal and can it be reflected in the mandate; will it be possible to formulate a clear mandate for the peacekeeping operation; and will it be reasonably possible to ensure the safety of the UN personnel, in particular by acquiring guarantees from the key parties or groups in order to ensure safety of the UN staff.

Should the Security Council find that deploying a peacekeeping mission is the most adequate measure, it formally authorizes the mission through a resolution which stipulates its mandate, scope and objectives. The General Assembly (“GA”) then approves the mission’s budget and resources.

In compliance with Article 17 of the UN Charter, financing a peacekeeping operation is the collective duty of all member states, and under such duty they are bound to pay in an assessed contribution towards the peacekeeping activities. The UN General Assembly allocates peacekeeping costs based on a special rate which is calculated in accordance with a complex formula agreed upon by the member states. This formula takes into account, inter alia, the relative economic situation of the member state. The permanent members of the Security Council are expected to bear the bulk of costs in line with their primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security.

The approved peacekeeping budget for the fiscal year from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014 amounts to about USD 7.83 bln [7]. For comparison, this is less than 0.5% of the world’s total defence expenditures (which in 2013 reached nearly USD 1,747 bln) [8]. At the same time, the UN regular 2012-2013 budget totals almost USD 5.57 bln [9].

For a number of years now, due to the regular non-payment or late payment of contributions by quite a few member countries, the UN regular budget has been funded, among other things, by borrowing from the peacekeeping budget [10]. The leading countries, in terms of the size of their contribution to the peacekeeping funds in 2013, included: the US (28.38 per cent), Japan (10.83 per cent), France (7.22 per cent), Germany (7.14 per cent), the United Kingdom (6.68 per cent), China (6.64 per cent), Italy (4.45 per cent), Russia (3.15 per cent), Canada (2.98 per cent), and Spain (2.97 per cent) [11].

Under certain circumstances, the General Assembly may pass decisions on issues of peace and security despite the Charter’s provision limiting its powers. General Assembly Resolution 377 (V) of 3 November 1950, Uniting for Peace, allowed the GA to consider issues in question whenever the Security Council is not in a position to act as a result of the differences among its permanent members with the power of veto. This provision covers all instances when there are good reasons to believe there has been a threat to the peace, breach of peace, or an act of aggression. The General Assembly may look into this matter to recommend that member countries adopt collective measures in order to maintain or restore international peace and security. This is an attempt to obviate the need for the Security Council’s authorization of the peacekeeping mission. Throughout the history of peacekeeping by the United Nations, the resolution above was invoked only once, in 1956, when the General Assembly passed a resolution establishing the first UN emergency forces in the Middle East.

3. Appointing senior officers

As a rule, the Secretary-General will appoint the head of mission (it is usually his Special Representative) to supervise the peacekeeping operation. The head of mission reports to the Secretary-General’s deputy for peacekeeping at the UN Headquarters. The Secretary-General will also appoint the Peacekeepers’ Force Commander, the Police Commissioner and the senior civilian staff. The Department of Peacekeeping Operations (“DPKO”) and the Department of Field Support (“DFS”) are responsible for recruiting civilian staff for peacekeeping operations.

The Special Representative, DPKO and DFS plan the political and military aspects, operations and peacekeeping support.

4. Who sends peacekeepers?

The United Nations does not have its own armed forces or police, so each time military and police contingents for the peacekeeping operation are provided by the members at the request of the United Nations. Peacekeepers wear the military uniform of their respective countries, and their affiliation with the UN peacekeepers is reflected only by their blue helmets or berets and identification insignia. The peacekeeping civilian personnel include international civilian officers recruited and deployed by the UN Secretariat. The peacekeeping operation is established in the shortest possible time, depending on the security conditions and the political situation on the ground.

As of 10 April 2014, the total number of staff serving in the 16 peacekeeping missions which are managed and maintained by the DPKO stands at 118,111, of which the uniformed personnel account for 97,518, including 83,571 troops, 12,094 police and 1,853 military observers; civilian personnel stands at 16,979 (as of 31 March 2014), including 5,256 international, 11,723 local; 2,020 UN Volunteers, and 11,517 officers [12]. Altogether 122 countries have contributed troops and the police. The total number of casualties suffered by current peacekeeping operations is 1,445. As of 30 April 2014, the top 10 troops contributors, ranked by the number of their peacekeepers, are as follows: 1) India (8,132), 2) Bangladesh (8,034), 3) Pakistan (8,027), 4) Ethiopia (6,628), 5) Ruanda (4,709), 6) Nigeria (4,614), 7) Nepal (4,612), 8) Ghana (2,992), 9) Senegal (2,967), 10) Jordan (2,729) [13].

Since the establishment of peacekeeping operations using military observers and UN troops, the former Soviet Union and later Russia (the Russian Federation), as a permanent member of the Security Council, have actively contributed to the definition of the key principles that govern staffing, planning, engaging, command, logistics, operations and funding.

The Russian Federation’s contribution to UN peacekeeping activities can be deemed reasonably active: as of 30 April 2014, Russia has contributed peacekeepers to 8 out of the 17 peacekeeping missions (Western Sahara, Haiti, Congo, Kosovo, Liberia, South Sudan, Cote-d’Ivoire, and the Middle East) [14], and holds 64th place out of 122 force contributors [15] with a contingent of 112 troops, including 41 policemen, 67 UN military experts and 4 troops [16].

Peacekeeping by the UN and regional agencies

Chapter VIII of the UN Charter, specifically its Article 52, stipulates that regional treaties or agencies can take part in the maintenance of international peace and security, provided such treaties or their bodies are compliant with the missions and principles of Chapter I of the UN Charter. However, in his statement of 16 September 1998, the SC Chairperson highlighted the primary role of the United Nations in establishing common peacekeeping standards, and emphasized that the Security Council should at all times be informed fully about the peacekeeping missions performed or planned by regional or sub-regional institutions and/or treaties [17]. In addition, through the Statement by its chairperson of 30 November 1998, the Security Council affirmed that any activity pursued within the framework of regional treaties or by regional bodies, including enforcement measures, should be compliant with Articles 52, 53 and 54 of Chapter VIII of the UN Charter, while the Security Council’s authorization of actions by regional and sub-regional agencies, or member states, or by a coalition of states, can be one of the most efficient ways to respond to conflict situations [18]. Thus, regional agencies must not violate the UN Charter or perform their peacekeeping operations outside UN sanctions authorizing such campaigns, as was the case with the unilateral use of force by NATO against Belgrade. Also, peacekeeping should not exceed the mandate of the Security Council (the NATO operation in Libya was an example of such violation).

There has been an overall tendency in the past several decades to give regional agencies a stronger role in peacekeeping, both on their own and together with the UN. A number of institutions, such as NATO, the EU, WEU, ASEAN, OSCE, OAS, OAU, CIS, and the African Union (“AU”), have formulated their own concepts of peacekeeping, and the majority of them have tried them out in practice. Take, for example, the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur, referred to by its acronym UNAMID, which so far has been the largest peacekeeping mission in the world [19].

The Future of Peacekeeping

Since modern conflicts are usually very intense, with protracted or sluggish armed clashes (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Somali, Trans-Dniester, etc.), resulting in numerous civilian casualties, peacekeeping activities in their various forms and shapes will continue to be necessary in the near future.

Peacekeeping operations have been very successful in preventing conflicts from escalating, while their success in fulfilling their mandate in its entirety or limiting the number of casualties has been rather limited [20]. What is undoubtedly true is the fact that peacekeeping is not a magic bullet, but only part of a range of efforts to facilitate conflict resolution; the ultimate solution remains, first and foremost, with the warring parties. Throughout all of its history, the successes of peacekeeping operations speak in favour of their continuation but also point to the need to make peacekeeping more efficient. In particular, one issue in peacekeeping, its anti-terror component, remains unresolved [21].

The current reality makes it imperative that new requirements be introduced in peacekeeping. First, all peacekeeping operations should be able to make a difference for the affected people early on in the mission, and the head of the mission in particular should have a right to use some of the mission’s funds to pay for the projects that could quickly improve the life locally, thus making the mission credible. Secondly, “fair and free” elections should be part of a broader effort to strengthen bodies of government. Thirdly, resources committed by member countries should be used with the utmost cost effectiveness. Fourthly, the human rights component in any peacekeeping operation is essential for efficient peace-building. Fifthly, crucial for post-conflict stability and mitigation of the threat of a resumed conflict are disarmament, demobilization, reintegrating former combatants and assisting the return of internally displaced people and refuges. Sixthly, any return to normal life in a post-conflict society lies exclusively through national reconciliation extending to all former conflict parties.

1. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N02/546/38/PDF/N0254638.pdf

2. www.un.org/ru/peacekeeping/resources/chronology

3. www.un.org/ru/peacekeeping/resources/statistics/contributors

4. www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/fatalities/documents/stats_2.pdf

5. www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/documents/bnote314.pdf

6. www.un.org/ru/documents/charter/chapter7

7. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N14/213/94/PDF/N1421394.pdf

8. www.un.org/ru/peacekeeping/operations/financing

9. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N13/454/15/PDF/N1345415.pdf

10. www.un.org/ru/aboutun/finance/regular

11. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N12/665/80/PDF/N1266580.pdf

12. www.un.org/ru/peacekeeping/resources/statistics/factsheet

13. www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/contributors/2014/apr14_2.pdf

14. www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/contributors/2014/apr14_3.pdf

15. www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/contributors/2014/apr14_2.pdf

16. www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/contributors/2014/apr14_1.pdf

17. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N98/273/95/PDF/N9827395.pdf

18. http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N98/376/49/PDF/N9837649.pdf

19. www.un.org/ru/peacekeeping/resources/statistics/factsheet

20. Bratt D. Assessing the Success of UN Peacekeeping Operations/The UN, Peace and Force in International Peacekeeping, Vol.3, No.4 (Winter 1996), published by Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

21. Zaemsky V.F. the UN and Peacekeeping. A course of lectures, 2nd edition, amended. Moscow, Mezhdunarodnyae otnosheniya, 2012. 328pp. (in Russian)

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |