Venezuela, a Nation Split Apart

Opposition students shouts slogans against

supporters of Venezuela's late President Hugo

Chavez during a protest a few blocks from

the electoral commission in Caracas,

Venezuela, Thursday, March 21, 2013.

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of Political Science, Director of Center for Political Studies of the RAS Institute of Latin America, Professor of Global Processes Department at Lomonosov Moscow State University, RIAC expert

The April 2013 snap presidential elections in Venezuela have exposed a country deeply polarized with a population divided into staunch supporters of the late leader Hugo Chavez and opponents of 21st Century Socialism. Further developments in the country will shape the future of leftist regimes in Latin America as well as Venezuela's relations with its strategic partners, including Russia.

The April 2013 snap presidential elections in Venezuela have exposed a country deeply polarized with a population divided into staunch supporters of the late leader Hugo Chavez and opponents of 21st Century Socialism. Further developments in the country will shape the future of leftist regimes in Latin America as well as Venezuela's relations with its strategic partners, including Russia.

Election Results and the Political Landscape

On March 5, 2013, a long and grave disease took the life of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, a vibrant and charismatic politician who had been at the helm of power since 1999. Chavez was the undisputed leader of the regional left, who had assumed Simon Bolivar’s idea of uniting Latin America in order to counterbalance the U.S.A. and had proclaimed the construction of 21st Century Socialism. Their model envisioned the nationalization of key economic sectors, tighter state regulation, and social reforms designed to suit the needs of low-income groups. These domestic processes were characterized by democratic procedures in parallel with stronger authoritarian trends that extended the rule and reinforced the leader’s powers, as well as placed restrictions on freedom of speech and activities of the opposition. Foreign policies have been based on confronting the U.S.A. and searching for alternate partners.

The April 14 snap elections offered a real opportunity only to Nicolas Maduro Moros, who was backed by the pro-government Gran Polo Patriótico or GPP, and to Henrique Capriles Radonski, the single candidate of Mesa de Unidad Democrática or MUD, the oppositional coalition of 30 mostly centrist and right-of-center parties and movements.

Both figures are not new to Venezuelan politics. Foreign minister from 2006-2012, Nicolas Maduro was appointed vice-president in 2012 and at the same time anointed as the successor of Chavez, to be followed by his acting presidency after the leader’s death. Twice elected governor of Miranda state, Henrique Capriles won the MUD primaries and became its single candidate, representing the Primero Justicia party. Capriles positioned himself as a proponent of Brazilian social-democratic model [1].

On the eve of the elections, the government expected a landslide victory but the outcome was a bombshell, as Maduro officially received 50.61 percent and Capriles 49.12 percent of the vote. Beginning in October 2012, Chavistas lost 658,800 votes [2]. The opposition declared numerous violations and demanded an audit of the registries and an exposition of dead souls and possible multiple voting, with the appropriate recourse to the Supreme Court. The MUD is also going to make appeals to international bodies. The National Electoral Council agreed to a partial recount of paper ballots, although the scheme makes no practical sense as electronic and paper ballots usually coincide in automated voting.

Public fever triggered by the national leader’s death also took its toll, as TV and radio programs on his life and work were run around the clock, while supporting the successor was interpreted as the deceased president’s last will.

Meanwhile, both sides took their followers to the streets. Of course, demonstrations brought victims and reciprocal accusations. Clashes also swept through the National Assembly, where opposition deputies, who did not recognize the legitimacy of the elected president, were deprived of voting rights and undertook protest actions. After May 13, over three thousand troops were deployed in the streets to counter crime and violence, while the use of the army for policing is causing concern by human right activists [3].

Why Polarization?

Venezuelan society has come apart to a great extent because of societal differences over the results of Chavez’s rule and ideological legacy. Chavistas accentuate the government’s social achievements: from 1999-2011, poverty fell from 49.4 to 29.5 percent, and extreme poverty – from 21.7 to 11.7 percent. In comparison to most countries of the region, Venezuela boasts the most balanced distribution of GDP (the Gini Index was 0.489 in 1999 and 0.397 in 2011) [4]. Caracas channeled two-thirds of its oil export revenues to social needs. Cubans have assisted in improving education and healthcare. Low fixed-price shops have been established for the poor, as well as specialized credit institutions that have helped to alleviate severe housing problems [5].

Almost fully under government control, electronic

media pictured Capriles as a candidate of global

imperialism and Zionism, eager to do away with

the gains of the Bolivarian Revolution; it also

depicted his followers as fascist right-wingers,

which resonated well with the poorly educated

segment of the electorate

Public fever triggered by the national leader’s death also took its toll, as TV and radio programs on his life and work were run around the clock, while supporting the successor was interpreted as the deceased president’s last will. The official candidate possessed strong administrative resources. Almost fully under government control, electronic media pictured Capriles as a candidate of global imperialism and Zionism, eager to do away with the gains of the Bolivarian Revolution; it also depicted his followers as fascist right-wingers, which resonated well with the poorly educated segment of the electorate.

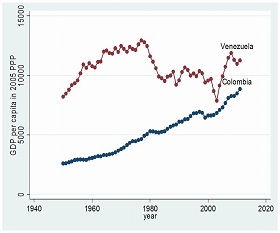

Capriles scored his votes from pervasive discontent about economy. From 2009-2010, GDP dropped from 3.2 to 1.5 percent. In 2011, the situation slightly improved [6], while in 2013 another downturn is looming. In early 2013, Venezuela was the regional leader in per-capita debt, with the state indebtedness running at 70 percent of GDP, while the budget deficit was at the 70-percent mark. State oil company Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) was over 40 billion dollars in the red, with oil output permanently falling [7]. In 2013, oil export is expected to fall by 7.8 percent [8]. Over the past decade, food imports have doubled, reaching 75 percent [9], 4,000 processing enterprises were closed, and the number of employers has fallen from 630,000 to 430,000. From 1999-2011, Venezuela's aggregate inflation rate, the region’s highest, reached 1,269 percent, whereas the increase in wages is only 1,018 percent. Beginning from 2008, the family basket of goods has not reached the subsistence level [10]. In February 2013, the fifth devaluation of the national currency took place, this time by 32.5 percent. As a result, year-on-year inflation skyrocketed to 29.4 percent, and the stock-out level to 21.3 percent.

The nationalization of large enterprises has brought about lower profitability, worsened the investment environment and foreign capital flight. Venezuela is the region’s weakest in competitiveness but leads in corruption. Pervasive violence and crime remain the country’s gravest problems. In 2012, Venezuela was the world’s fifth and the South American leader in premeditated murders per 100,000 population (54 according to government data, while NGOs insist on 73) [11].

The poor, who gain from numerous social programs, keep backing the authorities, while economic elites and the middle classes are switching over to the opposition.

Oppositional citizens are angry about converting the army into a pillar of the regime, the arms race, the use of administrative resources for recruiting ruling party support, offenses against independent media, selective justice, pressure on oppositional governors by withdrawal of economic levers, and threats of prosecution against government critics.

As a result, the poor, who gain from numerous social programs, keep backing the authorities, while economic elites and the middle classes are switching over to the opposition. Business is unhappy with operational restrictions, labor unions demand preservation of living standards and social guarantees, and students are protesting against infringements on university autonomy. Some members of the military are displeased with the army’s orientation towards 21st Century Socialism and the strong influence of Cuban advisors. The Catholic Church hierarchy also seems to be of two minds.

Situation in Venezuela and Latin America

The death of Hugo Chavez will definitely affect the future of 21st Century Socialism. There are many charismatic people in Latin American politics, but none could match the late Venezuelan president in popularity. Changes will occur to the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), a union launched by Venezuela and Cuba in 2004 that also incorporates Bolivia, Nicaragua, Ecuador and three small Caribbean states. The anti-market and anti-globalist project is based on solidarity and the complementarity of economies rather than on competition, and has been driven by Venezuela's sponsorship. Over the past five years, Caracas spent 33 billion dollars for these purposes, the key recipients being Cuba (18.8 billion), Bolivia (6.7 billion) and Nicaragua (5.5 billion) [12].

Venezuelan assistance virtually ensures the survival of the Cuban economy. In 2011, their bilateral trade turnover was at 8.3 billion dollars. Venezuela supplies Cuba with 100,000 barrels of oil daily at preferential prices to fill 62 percent of Cuban total needs. As of early 2013, there were over 30 various joint Cuban-Venezuelan enterprises. More than 40,000 Cuban doctors, educators and coaches work in Venezuela, while thousands of Venezuelan students are educated in Cuba [13]. Cubans are also quite important for Venezuelan security, including managing the protection of top officials.

Maduro is sure to do his best to protect and strengthen links with his strategic ally. In late April 2013, he visited Havana as a head of state to launch an additional 51 projects worth two billion dollars. One more proof of continuity is the May 4-5 summit of Petrocaribe, an alliance of Central American and Caribbean countries, which have proclaimed their willingness to reinforce the Venezuela-led bloc and use it for setting up a common economic area [14].

Despite Venezuela's efforts to diversify its economic relations, the U.S.A. is still its main trading partner and the key source of foreign currency.

Implementation of these plans to a large extent hinges on Venezuela. If dire predictions for its economy come true, Venezuelan aid would inevitably plummet and exacerbate the social environment in recipient countries.

Venezuela has become quite friendly with the South American common market Mercosur, set up in 1991 to incorporate Venezuela on the full basis in July 2012. In May 2013, Maduro visited Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay to both enlist the political support of their presidents and sign a number of mutually beneficial contracts. Caracas undertakes to expand oil supplies in exchange for basic foods and assistance in creating infrastructure for their storage and processing. Over the past five years, Venezuelan imports from Mercosur have constituted about 28 billion dollars, with 12 billion being food products. The new agreements are aimed at stepping up cooperation in the energy and farming sectors. And in June 2013, Venezuela is scheduled to chair the alliance.

Venezuela's President Nicolas Maduro talks to

the media after a wreath-laying ceremony at

the Jose Marti monument in Havana

April 27, 2013. Cuba and Venezuela signed

cooperation accords on Saturday for 51 projects

as Maduro, on his first trip to the island since his

election, pledged to maintain the close alliance

forged by his late predecessor, Hugo Chavez.

Set up in 2008, the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) has provided a platform for a relative regional consensus on Venezuelan events. The bloc unites 12 countries and is meant to ensure mutual understanding of diverse political regimes and settle regional problems without U.S. or EU participation. UNASUR observers attended the Venezuelan presidential elections, and on April 15, at an extraordinary summit in Lima unanimously recognized Maduro's presidency and called upon Venezuelans to put an end to violence and to launch a tolerance-based dialog.

Venezuela maintains quite reasonable, although more restrained relations with the Pacific Alliance, a community established in June 2012 to unite moderate Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile, as well as Central American states on an associational basis. In contrast to the Organization of American States (OAS), which permanently blasts Caracas with criticism, Venezuela is plausibly constructive within the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), launched in 2011 with the participation of Hugo Chavez. (The OAS has suspended Cuban membership, while the U.S.A. and Canada are not CELAC members.)

The U.S. Relationship

Venezuela's relations with the United States remain complicated. To bolster his anti-imperialist rhetoric, Nicolas Maduro also expelled two American diplomats two days before Chavez's death. There have also been statements on the implication of U.S. secret services in his disease. After the elections, Washington has been accused of destabilizing the country to justify foreign intervention and even of an attempt to assassinate Maduro. American officials, in their turn, have repeatedly expressed concern about political polarization and the absence of dialogue, and also have assured that Obama's administration is interested not so much in the election outcome, as in the observance of democratic practices and guarantees for the opposition as a part of the democratic process [15]. The U.S.A. is the only major power to withhold recognition of Maduro's legitimacy.

Nevertheless, the two sides may as well opt for healthy pragmatism based primarily on economic interests. Despite Venezuela's efforts to diversify its economic relations, the U.S.A. is still its main trading partner and the key source of foreign currency. It seems inconceivable for the United States to give up Venezuelan oil imports, and for Venezuela to switch over to other markets. In other words, the overall normalization of diplomatic relations does not seem unlikely on the basis of mutual respect and noninterference in internal affairs.

Relations with Russia

Bilateral cooperation was stepped up after 2005 on direct instructions from Hugo Chavez. In 2005-2012, trade turnover soared from 77.5 to 1944.7 million dollars, with the Russian share of exports over 99 percent in 2012. Deliveries are dominated by machinery, equipment, and vehicles (50.3 percent), other goods (40.1 percent), and chemical products (5.6 percent) [16].

Venezuela is Russia’s third largest arms market after China and India, with overall agreements concluded by the end of 2012 assessed by Rosoboronexport at 11 billion dollars. Most Russian weapons have been supplied on credit – Venezuela received 2.2 billion dollars in 2009 and four billion dollars in two installments in 2012 and 2013.

The two countries have a sizeable oil production contract, with 60 percent of the project held by Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) and 40 percent by a Russian consortium of Rosneft, Gazpromneft, TNK-BP and Lukoil [17]. During his visit to Venezuela last February, Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin promised to invest 10 billion dollars in the running projects [18]. By 2019, joint Russian and Venezuelan investments are to reach 46.9 billion dollars, with Russia’s share at 17.6 billion dollars [19]. The scope of cooperation also includes a functioning joint bank, Russian participation in the construction of standardized homes, and peaceful atomic cooperation. Talks are underway over engineering, extraction of bauxites and alumina and aluminum production, as well as over deliveries of long-range aircraft, tankers, vessels, etc. Both parties are interested in mutually beneficial cooperation but the degradation of Venezuelan political landscape may spawn difficulties in the repayment of Russian loans and contract observance.

Scenarios

Vladimir Davydov:

Latin America and the Caribbean Development

Forecast until 2020

Venezuelan politics are still quite uncertain, and depend on numerous economic factors and the positions of the conflicting parties. Because of the political crisis, both the government and the opposition will have to work hard to stay united. Destabilization may cause a split in the armed forces because most enlisted men come from low-income families while the top brass is not entirely socialist-minded.

In the short term, the Chavistas are likely to hold power but due to the worsening economy, the saucepan riots will continue, the regime’s social base will contract, and the opposition is likely to reject the vote audit results and in three years will attempt to force the president to resign early. A color revolution and repeat elections with reputable international observance appear less probable.

Under an optimistic scenario, the confrontation comes to an end, both sides drop their radical demands, the government shifts to moderation in its policies and launches a dialogue with business associations, opposition and foreign investors for the development of a consensus approach to overcoming the crisis and possibly creating a coalition government.

Due to the worsening economy, the saucepan riots will continue, and the opposition is likely to reject the vote audit results and in three years will attempt to force the president to resign early.

Negative scenarios imply chaos and radicalization of the regime that might step outside of legal boundaries and use force to quell protests. Such a confrontation is likely to spill over into an armed conflict, with Venezuela becoming a regional flashpoint, something unwelcome either to Venezuela or its strategic partners or even ideological opponents.

Should the opposition come to power, its government is supposed to try to preserve the current social programs, although austerity seems unavoidable for cutting the budget deficit, economic recovery and restoration of the market-oriented principles. Relations with Latin American partners should become more pragmatic, the first step being the discontinuation of free aid on an ideological basis. The new regime will also kick off a rapprochement with the United States. With an external threat no longer at hand, weapons acquisitions will shrink, while mutually beneficial hydrocarbon cooperation with other states, including Russia, will go on. In the absence of a constructive dialogue, regime change is not likely to stabilize the country, since the new government will face a leftist opposition as large as half of its populace.

1. See platforms of main candidates at the website of Venezuelan National Electoral Council: http://www.cne.gob.ve/web/normativa_electoral/elecciones/2013/presidenciales/documentos/programas/NICOLAS_MADURO.pdf; http://www.cne.gob.ve/web/normativa_electoral/elecciones/2013/presidenciales/documentos/programas/HENRIQUE_CAPRILES.pdf

2. El Universal, Caracas, 24.04.2013.

3. El Nuevo Herald, Miami, 11.05.2013.

4. CEPAL. Anuario estadístico de América Latina y el Caribe 2012. Santiago de Chile, 2013.

5. For details see: E.S.Dabagyan. Venezuela: The Trajectory of the Political Process. Moscow, 2011. Pp.137-139.

6. CEPAL. Anuario estadístico de América Latina y el Caribe 2012. Santiago de Chile, 2013.

7. http://www.infolatam.com/2013/04/24/incertidumbre-sobre-el -futuro-de-cubazuela/

8. El Nuevo Herald, Miami, 03.05.2013.

9. http://www.infolatam.com/2013/04/24/incertidumbre-sobre-el -futuro-de-cubazuela/

10. http://www.cne.gob.ve/web/normativa_electoral/elecciones/2013/presidenciales/documentos/programas/HENRIQUE_CAPRILES.pdf

11. Cited by: http://www.bbc.co.uk/mundo/noticias/2013/04/130412_venezuela_elecciones2013_previa_domingo_yv.shtml

12. El Nuevo Herald, Miami, 07.08.2011.

13. Venezuela: The Bolivarian Project Practice (Outcomes and Risks) (Ed. by V.Davydov). Moscow, 2011. P. 39; http://www.infolatam.com/2013/04/24/incertidumbre-sobre-el -futuro-de-cubazuela/

14. El Nuevo Herald, Miami, 07.08.2011.

15. http://www.bbc.co.uk/mundo/, 08.05.2013; http://www.panorama.com.ve, 09.05.2013.

16. Cited by: Venezuela: The Bolivarian Project Practice (Outcomes and Risks) (Ed. by V.Davydov). Moscow, 2011. P.75; Rossyiskaya Gazeta. 03.06.2013.

17. Rossyiskaya Gazeta. 03.06.2013.

18. Izvestiya, 06.03.2013.

19. http://www.embavenez.ru/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=876%3Arusia-y-venezuela-estrechan-relaciones-con-acuerdos-de-cooperacion-en-el-sector-petrolero&catid=35%3Aeconomia&Itemid=103&lang=ru

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |