UN Climate Summit: Are Countries Ready To Go Green Together?

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

On September 23, 2014 New York hosted the UN Climate Summit, which was accompanied by massive demonstrations by environmentalists in the United States, Europe and Australia. Although the regulation of harmful carbon emissions and deforestation are central on the climate agenda, the establishment of a new international regime is still underway as countries markedly differ on the issue. RIAC expert Igor Makarov, PhD in Economics, Associate Professor of the World Economy Department at Higher School of Economics, comments on the situation.

On September 23, 2014 New York hosted the UN Climate Summit, which was accompanied by massive demonstrations by environmentalists in the United States, Europe and Australia. Although the regulation of harmful carbon emissions and deforestation are central on the climate agenda, the establishment of a new international regime is still underway as countries markedly differ on the issue. RIAC expert Igor Makarov, PhD in Economics, Associate Professor of the World Economy Department at Higher School of Economics, comments on the situation.

Dr. Makarov, the UN Climate Summit was preceded by mass actions in New York, Washington and many European and Australian cities where people came out against carbon dioxide emissions and other noxious gasses. Were these issues central on the event’s agenda?

The New York summit has in fact proven to be a significant stage in climate change negotiations. It was not just a regular conference within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held to discuss the status and prospects for an international climate regime but an extraordinary gathering convened by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon ahead of the UNFCCC conferences in Lima in December 2014 and in Paris in 2015.

The emergency has been caused by the absence of a breakthrough in reaching a new climate agreement to be adopted in 2015 in Paris and come into force after 2020. States are still failing to find compromises on several key issues as vividly demonstrated by the 2013 UNFCCC Warsaw conference where delegations of over one hundred developing countries and then NGO representatives left in protest.

Mr. Ban believed that a meeting of over one hundred heads of state could give the climate talks a new impulse, since these top figures had an opportunity to declare national plans on cutting emissions and to discuss their visions of future climate accords. The conferees were not expected to sign any final official document but rather to gain the chance to freely exchange opinions, in contrast to climate talks full of heated debates on details and wording. Also of importance has been attracting public opinion, among other things through the invitation of Leonardo DiCaprio, in order for civil society to influence the positions of their countries two months before the Lima conference.

Expectedly, the summit failed to bring immediate results. Most representatives of leading states confined themselves to trite statements on the significance of opposing the climate threat. Speaking of national plans to reduce emissions, officials mostly reiterated promises from previous UNFCCC conferences. More ambitious turned to be the goals of the signed declaration of forests (a twofold reduction of the devastation rate by 2020 and putting an end to deforestation by 2030), although the document has no legally binding effect. Among state leaders, President Obama attracted the greatest attention by saying that the United States is ready to actively participate in global climate cooperation and called upon China to fully join the process, similar to what he said in 2009 on the eve of the Copenhagen summit in New York at a another high-level meeting that proved ineffective in preventing the failure of the climate agreement.

Whose interests will inevitably clash? How can differences between countries be resolved?

In recent years, the main fault line has lied between the industrialized and developing countries because of the UNFCCC principle of "common but differentiated responsibilities" which places the obligation to reduce emissions mostly on the more industrialized states. Since developing economies are growing very quickly and keep emitting more and more, this principle is definitely growing obsolete. Hence, industrialized countries are demanding an equalization of emission obligations (perhaps with privileges for the least developed states), while the developing world insists on maintaining the status quo.

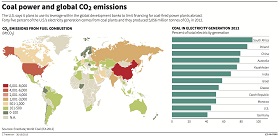

The positions of China and India, the world's first and third largest emitters, are of key significance, as they had no quantitative obligations under the Kyoto Protocol. Hence, the format of their participation in a new agreement seems decisive. So far, Beijing and New Delhi have refrained from full-fledged obligations, only checking the cooperative aspirations of other countries that see countering the climate change as pointless without the participation of China and India.

The industrialized world is also far from united, since some states, primarily the U.S., do not want to concede to a legally binding post-Kyoto accord if China opts out of full-blown commitments.

Due to their cumbersome decision-making procedure, the recent UNFCCC conferences have proven incapable of settling the range of the above-mentioned differences. The leading countries tend to augment the negotiations format by additional platforms, most of them bilateral. The New York summit was an attempt to bolster the multilateral regime by establishing an additional forum for discussing the snowballing problems. This is unlikely to shift the existing positions of the key countries, but may at least help to promote mutual understanding and trust, two things obviously in short supply at global climate talks.

Has there been any progress in developing the next Kyoto Protocol to replace the expired document? Do you see any prospects for transforming the so-called flexibility mechanisms, i.e. quota trading, joint implementation and clean development arrangements?

Yulia Yamineva:

International agenda on climate change: what

are the prospects for a new treaty?

:

Currently, the international climate regime is an organism in transition. Round two of the Kyoto Protocol has been in effect since 2013, but in the industrialized club, only the EU and Australia are fulfilling their quantitative emissions obligations. The post-Kyoto agreement is expected to come into force in 2020 after its signing at the UNFCCC conference in Paris in 2015.

No major progress in its preparation can be seen so far. As far as the Paris event is concerned, many pundits expect the parties to sign only a framework agreement with no concrete commitments on reducing emissions. Actually, the UNFCCC Warsaw conference went as far as replacing the term commitments by more neutral one – contributions.

In the absence of legally binding obligations, the flexibility mechanisms (clean development, joint implementation and intergovernmental quota trading) of the Kyoto Protocol appear irrelevant. At the same time, the carbon market is unlikely to fade away. On the contrary, it should keep booming, although as a totality of national quota trading systems that will continue to merge. At the New York summit, 73 national governments and heads of many major corporations supported setting emission prices in order to set a foundation for launching carbon markets.

Also within the global regime, we are going to see the advancement of non-market mechanisms for financing projects aimed at cutting emissions and fostering adaptation in the poorest countries. The Green Climate Fund was established back in 2009, and in New York, several countries pledged new contributions. Discussions are also underway about its adjustment, with China ready to participate. These discussions of technicalities will continue in Lima.

What about Russia? Is it going to increase its role in this area of international cooperation and in what way, should it happen?

Since Russian leaders stayed away from the New York conference, one might presume that climate change is not on Moscow's priority list. Russia refused to give quantitative commitments within round two of the Kyoto Protocol, but at the same time passed a national law to reduce emissions by 2020 to 75 percent of 1990 volumes. In New York, Russia showed a readiness to participate in the post-Kyoto agreement and cut emissions by 2020 to 70-75 percent of 1990 volumes, however insisting that the new agreement must be comprehensive and legally binding.

Currently, Russia is the world's fourth largest emitter and formally one of the most successful countries in reducing greenhouse gases emissions. Russia's transformational decline of the 1990s brought about the closure of numerous gas dischargers, so by 2012, its emissions were 30 percent below the 1990 level. The situation still provides Moscow with ammunition at talks, but it cannot last forever. The 25-percent reduction against the 1990 level planned by 2020 (just like the 25-30-percent cut by 2030) seems far from ambitious, but rather fits the basic scenario and generates misunderstanding on the part of negotiating partners. The only way to overcome the confusion appears to lie in the true de-carbonization of Russian economy through the modernization of the energy sector, improved technologies and the construction of a system for regulating greenhouse emissions.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |