With the American contingent of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) almost out of Afghanistan, analysts in Russia and other countries are quick to review Washington's errors in the context of Moscow's experiences 1979-1989.

Next December, the American-led ISAF, established following the Security Council Resolution of December 20, 2001, will complete its mandated mission in Afghanistan. According to the Afghanistan Study Group, the operation has cost the U.S. budget USD 600 billion, while Harvard University experts assess the economic damage at a shocking one trillion dollars. As of last April 4, there had been 2,178 American fatalities, 83 percent of them people who were killed in action, and 19,523 has been wounded.

ISAF Reformatting and Withdrawal from Afghanistan

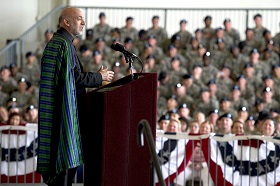

After 2014, the Pentagon and NATO plan to convert ISAF into a training mission, with ISAF Commander General Julive Danford proposing to leave 12,000 foreign troops, 8,000 of them American, in Afghanistan. About 2,000 would be tasked with counterterrorist operations under codename Resolute Support, to assist Afghan authorities and security forces in training their army and special-purpose units, and to advise them in operations against terrorist and extremist groups active in the country. The new mission’s status has not yet been defined, largely because of President Karzai’s refusal to sign a security agreement with Washington and its NATO allies that would give the remaining foreign troops immunity from prosecution. Consequently, the White House is also mulling the zero option i.e. the complete withdrawal of American troops.

Since 2013, ISAF has been moving large contingents and equipment out of Afghanistan along three main routes: the Southern Distribution Network – by road through Pakistan to the port of Karachi and by sea to their final destinations; the Northern Distribution Network – by road or railway through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and Georgia or Russia to Latvia; and the combined route – by C-17s, C-130s and Boeing-747s aircraft directly home or to the Persian Gulf or Mediterranean ports for onward shipment by sea. NATO experts believe the logistical operation to be the largest and costliest in the bloc’s history, with withdrawal of the U.S. contingent alone – involving 20,000 containers of equipment, 24,000 pieces of rolling stock and 38,000 troops – costing seven billion dollars. There are alternatives, however: some of the weapons and equipment could be transferred or sold to the countries in the region. According to newspaper Kommersant, the DoD is allegedly is raising that possibility with the governments of Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Kabul and Islamabad are also interested in some of the military assets for counterterrorist purposes.

Many U.S. and European analysts are quite skeptical about the military and political outcomes of ISAF’s involvement, noting that the Soviet experience in Afghanistan has been largely left to one side (1, 2).

The Unlearned Lessons of Soviet Military Presence

The United States has hardly ignored the Soviet experience in Afghanistan. On the contrary, after the withdrawal of Soviet troops and before launching its 2001 Afghan intrusion, the U.S. military undertook a painstaking analysis of the 40th Army’s combat strategy and psychological operations, the approach taken by the KGB and the Defense Ministry’s Chief Intelligence Directorate, all of which has definitely helped NATO avoid more substantial losses during their more than decade-long presence in Afghanistan. At the same time, despite advice from their Russian counterparts, the White House and the DoD gave little regard to rebuilding the Afghan economy, infrastructure projects, and modernizing the country’s agriculture sector, which is currently focused on narcotics. The USSR left the country after building 150 facilities, with the same number underway. It built the 2.7-kilometer-long Salang tunnel – a world record at the time – through a strategic pass in the Hindu Kush Mountains to link the northern and southern parts of the country. However, errors by both Soviet and American forces have long been the focus of much of the expert debate about events in Afghanistan, which seems to highlight three common failures.

No Cooperation Military-Civilian Cooperation

Neither the U.S.A. nor the USSR chalked up particular successes in establishing contacts with Afghan tribal leaders, the Pashtun in particular. Afghan society – centuries-old, highly conservative and religious – has long been led by merchants, private owners, and clerics, and this was something Moscow completely rejected in the 1980s. The problems stemmed from the communist program of enlightening the Afghans through replacing religious education with secular studies and undermining the authority of the local Muslim clergy. General Ruslan Aushev, a distinguished Soviet veteran of the Afghan campaign, says that Moscow made a key ideological mistake by insisting that "religion is the opium for the people".

The U.S. commanders have been trying to heed the local cultural specifics. In one of his reports, General Stanley McChrystal, ISAF commander from June 2009 to June 2010, emphasized that American soldiers should step up communication with the locals, understand their mentality, and ensure they are informed about their history and culture (1, 2). At the same time, American attempts to rehash the traditional system of tribal alliances by planting democratic values, such as gender equality, universal modern education, including the use of the Internet, and the election of legislative and executive authorities, were far from being a success. For example, girls' schools have been often attacked by radicals. As for the presidential elections, after the first round, which saw Abdullah Abdullah take the lead, the key runners have plunged into nondemocratic bargaining, with Mr. Karzai's people trying to gain privileges and immunities, as is clear from the statement by Zalmai Rasul, ostensibly the proxy of the lame-duck president. Further, after the Taliban's statement on launching the springtime terror campaign, the second round may as well be cancelled, since the Taliban is deemed to control up to one-third of the territory (1, 2).

It is also important to note that any extended war – ten years of Soviet and almost 13 years of the American presence – is pushing soldiers to cruelty and indifference, and generating a culture of violence toward the local population, while the use of force becomes a way of life (1, 2). Consequently, by the time the ISAF mission winds down, America’s enemies (the Taliban, al-Qaeda and affiliated terrorist and extremist cells) will have been bolstered by the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). In 2013, 12 ISAF servicemen were killed and 10 wounded in so-called green-on-blue attacks, which take their name from the colors used on the military map where blue indicates NATO forces and green marks the Afghan army and police.

Gradual Involvement in the Afghan Domestic Conflict

Another error that Soviet and American forces have in common (1, 2), is their gradual involvement in inter-tribal disagreements. Initially, the Soviet Union’s limited contingent had been tasked with protecting strategic facilities, the USSR state border, and the integrity of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. However, the February 1980 antigovernment riots in Kabul instigated by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, then head of the Muslim Youth organization, and Burhanuddin Rabbani, the leader of Jamiat-e Islami Afghanistan, forced Moscow to consent to joint combat operations with Afghan forces against the opposition troops that had been relentlessly attacking Soviet contingents.

The Pentagon had planned to complete its counterterrorist operation against the al-Qaeda and Taliban within one year, or three to five years at most, but the coalition forces found they had to stay much longer. Against the backdrop of a hemorrhaging of support for (1, 2) Mr. Karzai, a Pashtun from the Popolzai clan, supported by the White House in the 2004 elections, U.S. forces found themselves bogged down in an emerging civil war. Many provinces are still warring, with a number of groups opposing each other within the government, i.e. Tajik ministers are openly clashing with Uzbeks, while the Pashtuns are challenging both. The former mujahedeen are deeply involved in bribery, corruption and embezzlement, with the president's brother Mahmud Karzai and a close relative of First Vice-President Haseen Fahim suspected of stealing USD 861 million from Kabul Bank (1).

In an environment like that, Washington also plunged into the power struggle between opposing groups on the Afghan domestic scene, attempting to create dialogue with the Taliban and engage it in the country’s political life by giving its leaders government posts, this shoring up a U.S.-friendly regime and helping ensure a safe exit for Western troops when the time comes (1, 2). In its most recent attempt, the White House, assisted by Pakistan and several Scandinavian countries, including Norway, tried to open the so-called Taliban Political Office in Doha, Qatar, and launch peace talks on Afghanistan. However, this proved just another disappointment, largely because of Mr. Karzai, who was indignant about the flag of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the country's name under Taliban rule in 1996-2001, flying over the office.

Hasty Withdrawal

Another blunder seems to lie in the hasty withdrawal of forces. Many Russian historians and Afghanistan campaign veterans feel that, in 1989, the Soviet Union was too eager to fulfill its obligations to the West and failed to calculate the consequences of its actions for the friendly regime in Kabul (1, 2, 3). In fact, in leaving Afghanistan, Moscow left its allies face to face with heavily armed opposition forces. As a result, all those known to have cooperated with the Soviets were either killed or persecuted, with Mohammad Najibullah, the last president of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, slain on the spot (1, 2). According to Zamir Kabulov, Director of the Second Asian Department at the Russian Foreign Ministry and Special Representative of Russia’s President, NATO’s desire to speed up the transfer of powers and territories under ANSF control, paying little heed to the realities on the ground, seems imprudent at the least. Provinces where there is no Western military presence are visibly falling under extremist influence. Late 2012 saw an acute aggravation of the situation in Faryab, which was followed by similar issues in Kapisa, Uruzgan, Herat, Kunduz and Badakhshan.

Crucially, with the completion of the ISAF mission on the horizon, the non-Pashtun elites increasingly fear a Taliban resurgence. Consequently, centrifugal trends are on the rise, with skyrocketing ethnic tensions that impact public sentiments and push tribal leaders to separatism. After reelection in 2009, Mr. Karzai alongside his Pashtun entourage and with support from key Western allies, focused on removing influential Tajiks from the government and security forces. On March 10, 2011, a suicide bomber killed General Abdul Rahman Saidkhaili, the police chief of Kunduz Province, who was seen as the staunchest opponent of the Taliban, and six months later commander of the 303 Pamir Corps Daud Daud was assassinated. Afghan analysts believe their elimination comes from a worsening Tajik-Pashtun turf war within the security forces. The Tajiks responded by scheming to weaken Mr. Karzai’s Pashtun entourage, i.e. to foil the plans of the Taliban that had targeted a number of highly placed Tajiks, including interior minister Bismillah Khan, former head of National Security Directorate Amrullah Saleh, and governor of Balkh Province Atta Muhammad Nur. This list includes only those Tajiks who vigorously oppose the Taliban and a stronger Pashtun voice in government.

Afghanistan After 2014

Experts in Russia and elsewhere (1) are confident that without any foreign military presence Mr. Karzai’s corrupt and unpopular regime will last only months or weeks against the Taliban offensive. The White House and the DoD no longer conceal the fact that the ANSF is hardly fit for combat on its own due to a lack of weapons and hardware, in particular aircraft, as well as solid logistical and intelligence support, which means that the United States is likely to keep some of its contingent on in Afghanistan.

An analysis of the situation after the Soviet withdrawal and the future dramatic reduction of the Western forces in Afghanistan suggests there can be no long-term stabilization without an inclusive strategy that extends far beyond military methods. Peace only seems attainable through negotiations and compromise with leaders of all groups of the population, including the Taliban, which itself is a rather motley crew of various factions, including foreign mercenaries.

Since Afghanistan clearly lies within its sphere of interests, Russia is prepared to work together on its future with all interested states and international organizations, including the United States and NATO. Moscow and Brussels may boast healthy cooperation within the Russia-NATO Council’s Trust Fund which assists with the supply of spare parts and pilot training for Mi-17 helicopters operated by the Afghan army, personnel training for Afghan counternarcotics units, and the transit of cargo and military hardware for the ANSF across Russia.

The “2014 factor” highlights the need to continue this collaborative approach in work on the future operation Resolute Support, provided that there is continuous data exchange and maximum transparency.