Transnational Migration as an Issue of Political Theory

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of Political Science, Leading researcher, RAS Institute of Philosophy

At first glance, transnational migration appears unparalleled in scale. Whereas in 2000 there were 120 million people around the world residing outside countries of their birth, in 2003 the figure rose to 150 million, in 2005 – 180 million, and in 2009 – 214 million. And keep in mind that these are just approximations. Reliable statistics are hard to come by since a considerable portion of transnational migration is always off-the-books.

I.

At first glance, transnational migration appears unparalleled in scale. Whereas in 2000 there were 120 million people around the world residing outside countries of their birth, in 2003 the figure rose to 150 million, in 2005 – 180 million, and in 2009 – 214 million (1).And keep in mind that these are just approximations. Reliable statistics are hard to come by since a considerable portion of transnational migration is always off-the-books (2). Skeptics may say that transnational migration is a common historic event. Enormous group of people have travelled around the globe throughout the entirety of human history. During the relatively problem-free 19th century, millions went from Europe to America. Between 1850 and 1900, Norway lost a quarter of its population due to resettlement. Moreover, we tend to admire absolute figures, while in relative terms nothing extraordinary is occurring today. In 2006, the U.S.A. heatedly debated excessive immigration, which made up 13 percent of the core population, while in 1914, at the influx peak, the incomers' share was 15 percent.

Today, about one-third f transnational migration is completed not by settlers from impoverished former third-world countries to the well-off first-world, but from critically impoverished situations to less disadvantaged places of the same third and second worlds

In addition, we need to remember that although the flows from the global periphery (erroneously titled developing countries) to core states are impressive, much migration takes place between the periphery and semi-periphery of the world's political and economic systems. Today, about one-third (or one half, according to some data) of transnational migration is completed not by settlers from impoverished former third-world countries to the well-off first-world, but from critically impoverished situations to less disadvantaged places of the same third and second worlds, i.e. from Laos and Burma to Thailand, from Central Asia and Transcaucasia to Russia, from Mozambique and Botswana to South Africa, from Ukraine to Russia and Poland, from Bangladesh to India, from Guatemala to Mexico, from Pakistan, Nepal and Afghanistan to the UAE (3), Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and other petroleum monarchies of the Middle East. But still, skepticism about global migration is hardly justified, since the mass movement of labor migrants between countries is an integral part of economic and socio-cultural globalization, i.e. the growing interdependence of the world's separate parts. To this end, two points appear quite notable.

- If you will, for some states migration is a prerequisite for their existence, as one-third to half of their GDP comes in the form of remittances from their citizens working abroad. For Kyrgyzstan and Moldova, the figure is about 30 percent, for Laos – 35 percent, for Tajikistan – 37 percent, and for Guinea-Bissau – 48 percent. These figures are official, while in reality the situation may be even worse bearing in mind the non-uniform pattern of internal development. In certain regions of countries with relatively good macroeconomic characteristics, for example in Ukraine and Azerbaijan, deplorable economic conditions drive away practically the entire employable population elsewhere, many of them looking for jobs abroad (4). In other days, such political entities would not last long and would vanish for good (5). However, the current world system would hold up to fake sovereignty even if the fakeness is obvious.

- Political democracy in West European countries multiplied by trouble-free naturalization procedures has brought about notable changes in the ethnic and demographic structure of the population. In Germany, where belonging to the national community had long been defined by ethnicity, almost half of the population under 15 years of age (45 percent, to be exact) has an immigration history, which means that either a parent or a grandparent were born outside the country. In 2002, every eighth baby was born to a foreign mother in Great Britain, every fifth – in Switzerland, and six out ten – in the Netherlands. In 2005, immigrants composed 10 percent of Swedish population, while in 2010, the most popular name given to a newborn in London was Mohammed.

One may ad libitum lament about the decline of Europe but the fact remains. Today, European countries, just like North America, Australia and New Zealand, have immigration at their base. The same goes for Russia, which has become attractive to job seekers from the post-Soviet space and excessively populated Southeast Asian states, primarily China, due to its relative industrial edge and large labor market.

II.

For some states migration is a prerequisite for their existence, as one-third to half of their GDP comes in the form of remittances from their citizens working abroad.

Transnational migration is a multidimensional phenomenon with economic, demographic, political, socio-anthropological and socio-cultural aspects, which has given rise to a separate branch of knowledge, i.e. interdisciplinary migration studies. Unfortunately, in Russia these problems are analyzed mostly by demographers and economists (6). As far as political and social scientists are concerned, writings describe mostly security aspects (7), with rare exceptions (8). We will not cover the consequences of transnational migration, such as social tensions or crime, since these matters do require a separate survey, but only mention that a disproportionate attention to security is not likely to promote research in the migration field.

However, the point is not just in the theoretical deficit engendered by the security bias. The domination of the negative effects of immigration in the recipient society within the public debate in Russia gives rise to the neglect of its potential and the unwillingness to regard immigration as a resource of a economic, demographic and, notably, cultural nature.

III.

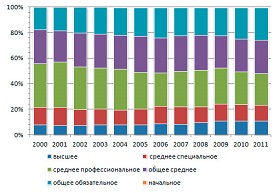

There are at least two prejudices about transnational migration that we would like to refute. Number one is related with the belief that migrants are mostly uneducated but in fact the situation is different. According to the World Bank (a sampling of 62 million migrants in 20 industrialized countries), 36 percent are college graduates.

To begin with, a differentiation should be made between forced and voluntary transnational migration (9). Voluntary migration means leaving the country of birth and permanent residence at one's own discretion, i.e. cases when individuals make up their minds to emigrate, for example resettlement of Indians and Pakistanis to Britain during the recent 50 years. Forced migration, on the contrary, involves the movement of masses to other countries against their will under the threat of extermination or starvation, as what happened to two million Iraqis who fled their homeland after the U.S. military strike and occupation in 2003.

According to the World Bank (a sampling of 62 million migrants in 20 industrialized countries), 36 percent are college graduates.

Since the subject of our attention is mostly voluntary migration, i.e. resettlement from the deprived South to the affluent North, one key socio-psychological factor seems to be quite significant. Basically, it is the most fluid, dynamic and adventurous individuals who dare to leave their country for good (10). Those deprived of sufficient resources, including moral and psychological assets, normally prefer to stay in their nest.

Prejudice number two is related to the view that migrants refrain from integrating into their recipient communities, which allegedly explains their marginal status and societal isolation (enclave-ization, ghettoization, etc.) to tacitly suggest that the heart of the matter is in the cultural differences. We believe that the logic should be reversed to imply movement from marginality to culture but not vice versa.

The marginality of migrants vis-à-vis the core population is a collateral (and unintended) effect of their social status.

Socio-economic motivation is the key to transnational migration, as well as to the social behavior of migrants at the new location. Courageous settlers are primarily concerned about the wellbeing of their own and of their children. Hence, their basic desire is to integrate into the recipient country. However, the problem is in numerous barriers. The labor market niche for most of them is usually hard, lowly and poorly paid work (11) that results in homes in low-cost city districts or outskirts. Concentrated poverty makes these areas a priori disadvantaged, with low-quality schools, high crime rate, miserable social infrastructure, high unemployment, etc., which takes the migrants into a vicious circle. In order to give up marginality and become normal, respectable members of society, they must leave their residential environment. But this can be made possible only through elevating their social status (income, education, etc.), i.e. to escape from the periphery. Thus, the marginality of migrants vis-à-vis the core population is a collateral (and unintended) effect of their social status.

The situation is aggravated by the cultural divergence overlaying the socialf differences. Marginals are mostly migrants, i.e. aliens and wrong believers, while migrants are mostly marginals, generating the illusion that the migrants' problems come from their cultural differences from the recipient population, from the unsatisfied demand for cultural identity, etc.

The thing I wish is to be properly understood. Unwilling to deny the importance of the immigration's cultural aspects, I would only like to underline the inadmissibility of the culturalization of social issues, interpretation of tensions and differences of socio-structural character as conflicts of culture. The point seems to be not in cultural differences per se but rather in superimposition of social and cultural differences.

IV.

Russia is an immigration country, with a dependence on immigration inflows possessing a structural character, since even the most prudent calculations indicate a loss of employable population of up to 12 million by 2025.

Research on transnational migration is rife with theories, with four key approaches competing to explain the origin and dynamics of various immigration regimes, (12) i.e. (1) economic, (2) state-centric, (3) culture-centric, and (4) instrumental.

1. Proponents of the economic approach focus on the calculation of immigration-caused gains and losses pertaining both to the receiving and giving countries. Gains for the donor countries include remittances and lower unemployment (quite important for labor-excessive regions), while on the negative side there is the outflow of professionals (doctors, nurses, engineers, etc.) essential for the state and the society. Migration-generated cons of the recipient countries put pressure on the wages and higher competition for jobs in certain industries, while the pros include a compensation in the labor deficit caused by a decreasing employable population, additional major inputs to GDP, and migrants' (including illegal) contribution in consumption as they significantly augment the state budget, at least in sales taxes.

2. The state-centric or institutional approach concentrates on the structure of bureaucracy and its preferences toward immigration, i.e. appropriate agencies and services, the original state model, etc. For example, in the U.S., immigration policies had long been the responsibility of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, but in 2002, following 9/11, the service lost its autonomy and became part of the Department of Homeland Security. As for the state model employed by the bureaucracy in different countries, there: (a) imperial, (b) liberal, (c) ethnic, and (d) multicultural versions.

(a) The imperial pattern was used by Great Britain until 1961 and the Netherlands until the 1980s. After the empires' breakdown in the second half of the 1940s, both countries provided residents of former colonies with free entry and subsequent naturalization.

The pure case of the multicultural model is

Canada after 1971 when Ottawa officially

proclaimed bilingualism and multiculturalism of

the Canadian nation

(b) The liberal model exists in most West European countries. Based on the concept of individual rights, it settles the entry and naturalization issues on the individual basis proceeding from the state's needs and obligations under international humanitarian conventions. However, currently liberal France used some imperial elements until early 1960s, extending special entry and naturalization norms to migrants from Algeria and Senegal.

(c) The ethnic pattern normally implies a regime based on the notion of the ethnic homogeneity value for the national community. The pure case was the FRG until the end of 1999, for in 2000 the effective law abolished the definition of national affiliation as an affiliation with the community of origin. Mixed ethnic-liberal patterns are employed by Spain, Greece and Italy.

(d) Finally, the multicultural model working in the states where immigration is handled on the basis of recognition of collective rights. The pure case is Canada after 1971 when Ottawa officially proclaimed bilingualism and multiculturalism of the Canadian nation. Mixed patterns are practiced by Sweden (13), the Netherlands from early 1980s to early 2000s (14), Austria (15), and Germany after 2000 (16).

3. The culture-centric approach to the formation of immigration regimes is firmly associated with Rogers Brubaker's classic work Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany [12]. His numerous followers believe that the development of immigration policy (entry plus naturalization) is determined by the country's political culture, which, in its turn, is shaped by the understanding of the national community's nature. Whereas France is committed to the nation's civil model and the citizenship law based on jus soli, Germany is attached to jus sanguinis focusing on the nation's ethnic essence.

Anatoly Vishnevsky:

The New Role of Migration in Russia’s

Demographic Development

4. The instrumental approach implies that the state's attitude to immigration and immigrants is by no means dependent on the specifics of political culture but on economic and political reasons. In contrast to proponents of state centrism, instrumentalists accentuate not the resources of the bureaucracy but the balance of powers formed by various political forces including parties, labor unions and ethnic organizations.

V.

In conclusion, it appears appropriate to underline once more that Russia is an immigration country, with a dependence on immigration inflows possessing a structural character, since even the most prudent calculations indicate a loss of employable population of up to 12 million by 2025.

Slogans about raising the birthrate voiced by some Russian politicians of the self-proclaimed conservative segment are pure demagogy. Even if each Russian woman of the childbearing age sets out to quixotically have three and more babies, they would enter the labor market in only 20-25 years.

With Russia becoming an immigration country, the national expert community is facing a challenge to theoretically examine the phenomenon of transnational immigration in every dimension; otherwise the moment will be missed.

Notes:

1. According to the International Organization for Migration.

2. On calculation methods used in current migration studies [8; 10].

3. Immigrants constitute 85 percent of the country's population, with similar figures specific to other countries in the list, which seem to provide a proper occasion to think about the origins of the subjects in oil monarchies.

4. For example, in early 2000s, every third Moldovan and Armenian household had one member working abroad. See [11].

5. We have in mind times when a nation state was not regarded as a modal form of the political system, i.e. the imperial period. Popular views concerning the nation and the nation state as a set of norms (along with other forms of political organization seen as pathologies) are systemically criticized by a group of Kazan historians publishing the Ab Imperio journal. For example see [3].

6. However, credit needs to be given to specialists from the Institute for Economic Forecasting who have been researching all aspects of migration during the last 15 years. For example see [2; 5; 6].

7. Migration is regarded as a threat to economic, sociocultural, ethnocultural and spiritual security. Giving names of authors with such views seems hardly appropriate as to refrain from propagating unworthy attitudes.

8. The group definitely includes sociologists Andrey Korobkov and Vladimir Mukomel, social geographer Olga Vendina, and historian Vladimir Dyatlov. See [7; 1; 4].

9. It appears feasible to mind the relativity of the difference. Processes perceived as voluntary migration are often driven by despair, i.e. an unbearable economic environment. Hence, voluntary migration to a certain extent is involuntary.

10. For example, young men leaving Central Asia to seek their fortune in Russia often sell their cows or houses or make debts expecting to become solvent in one or two years.

11. Harvesting in agriculture, painting and plastering jobs in construction, cleaning in hotels, dish washing in restaurants, etc.

12. See details on immigration regime in [9].

13. Up until the mid-1990s, Swedish law treated the minority rights issues equally for Finns, the Sami and immigrants.

14. In 1983, the Netherlands adopted a program for multicultural integration of immigrants through state sponsorship of ethnic organizations formed by foreign incomers. In 2003, multiculturalism was replaced by civil integration focusing on the obligatory engagement of migrants and their family members in special training and testing for language and knowledge of the Constitution.

15. Austria boasts broad cultural autonomy for historic minorities. In particular for Croatians and Slovenians, while from late 1980s to late 1990s, the state initiated and sponsored programs to support minorities formed by immigrants.

16. 16 The point in question is the above amendments in the Law on Citizenship of 2000 and the Law on Immigration of 2002.

Bibliography

1. Olga Vendina. Cultural Diversity and Side Effects of Ethnocultural Policies in Moscow // Kennan Institute in Moscow. Issue 13. Moscow: Kennan Institute, 2008.

2. G.S. Vitkovskaya. Forced Migration to Russia: the Decade Results // Migration Situation in the CIS Countries / Edited by Zh.A.Zayonchkovskaya. Moscow: Kompleks-Progress Publishers, 1999. Pp. 159-195

3. I. Gerasssimov, S. Glebov, A. Kaplunovsky, M. Mogilner, A. Semyonov (editor). The New Imperial History of the Post-Soviet Space. Kazan: Center for the Study of Nationalism and Empire, 2004

4. V.I. Dyatlov (editor). Transboundary Migrations and Recipient Society: Mechanisms and Practices for Mutual Adaptation. Yekaterinburg: Urals University Publishers, 2009

5. Zh.A. Zayonchkovskaya (editor). Labor Migration in the CIS: Social and Economic Effects / Research Center for Forced Migration in the CIS. Independent Research Council for Migration in the CIS and Baltic. RAS Institute for Economic Forecasting, 2003

6. Zh.A. Zayonchkovskaya, G.S. Vitkovskaya (editor). Post-Soviet Transformations: Reflection in the Migrations / Center for Migration Research. RAS Institute for Economic Forecasting, 2009

7. A.V. Korobkov, V.I. Mukomel. Migration Policies of the U.S.A.: Lessons for Russia. Moscow Bureau for Human Rights. Moscow: Academia, 2008

8. E. Krasinets, E. Kubishin, E. Tyuryukanovs. Illegal Migration in Russia: Selecting a Regulation Strategy // Immigration Policies of Western Countries: Alternatives for Russia / Edited by G. Vitkovskaya. Moscow: Gendalf Publishers, 2002. Pp. 227-259

9. V.S. Malakhov. Immigration Regimes in Western States and in Russia: the Theoretical and Political Aspect // POLIS journal. 2010. No. 3-4.

1. I. Molodikova, F. Dyuvel (editor). Transit Migration and Transit Countries: Regulation Theory, Practice and Policy. Moscow: Universitetskaya Kniga Publishers, 2009

11. S.V. Ryazantsev. Labor Migration in the CIS: Trends and Problems of Regulation // World Economy and International Relations journal, 2005, No. 11, Pp. 65-69

12. Brubaker R. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany, Cambridge, Mass. 1992.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |