The concept of the “global majority” has become one of the central elements of Russia’s new foreign policy rhetoric, reflecting Moscow’s intention to capture the transformations taking place on the world stage—the transition toward multipolarity, rise of the Global South, and the dismantling of the Western monopoly over the interpretation of international norms and institutions. Russia seeks not merely to position itself as part of the non-Western world, but to become one of the leading centers for the intellectual and political articulation of its interests. However, as the “global majority” concept gains traction among Russian official and expert circles, questions arise over the universality of this approach and its ability to resonate with foreign partners.

In this context, ASEAN presents an illustrative case—an association that over decades has developed its own model of regional interaction, grounded in the principles of consensus, inclusivity, and neutrality. As a result, a dilemma emerges: can the mobilizing logic behind the “global majority” concept be reconciled with ASEAN’s pragmatic, consensus-driven, and institutionally grounded diplomacy? If so, to what extent can this concept be embedded within the political culture of Southeast Asian states without provoking tension or rejection?

For Moscow, the “global majority” represents not only a tool for symbolic alignment with like-minded states in defending sovereignty and cultural diversity, but also a way to cast the West in opposition to the wider international community. However, any binary foreign policy framework is bound to arouse caution within ASEAN, as it would inevitably be perceived through the prism of bloc confrontation. In this regard, openly supporting and positioning itself as a part pf the global majority would, from ASEAN’s perspective, signify a departure from its long-standing policy of non-alignment, balance, and equidistance—thus drawing the Association into an unnecessary conflict with the United States and its Western allies. The loss, or even partial erosion, of ASEAN’s capacity for multi-vector diplomacy would constitute a “red flag” for the organization.

Another issue shaping the region’s perception of the “global majority” concept concerns ASEAN’s institutional identity. For the Association, it is vital to preserve ASEAN centrality—that is, to ensure that key regional dialogue platforms such as the East Asia Summit, the ASEAN Regional Forum, the ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting Plus, and ASEAN+3 revolve around ASEAN itself. Adopting the Russian concept carries the risk of devaluing ASEAN’s agency and political weight. In other words, ASEAN would come to be viewed merely as one component of a broader majority—an important one, perhaps, but still subsumed within a framework whose main priorities are defined externally. Such a symbolic “downgrade” contradicts the principles and undermines the very philosophy of ASEAN—to play a central role in the regional architecture.

Moreover, ASEAN member states generally show little interest in abstract geopolitical constructs; their priorities lie primarily in trade, investment, access to technology, and infrastructure development. For them, any concept gains significance only once it acquires material substance or is supplemented by concrete projects with expected benefits and Russia is not yet in a position to offer attractive economic proposals. Finally, ASEAN will not achieve internal consensus on the world majority because the positioning of this concept directly contradicts the policies of certain member states—such as Singapore, which openly condemned Russia’s actions in Ukraine and joined the anti-Russian sanctions measures.

Although current attempts to promote the “global majority” brand in Southeast Asia are unlikely to succeed, this does not preclude the possibility of successfully advancing certain elements of the concept, provided they are carefully adapted to the region’s target countries. First, it is necessary to reduce the ideological weight found in Russian discourse.

Russia’s “global majority” concept should not be presented as an anti-Western project or as an instrument of opposition to the West in Southeast Asia, as such framing would inevitably create tension within ASEAN, where any manifestations of bloc-oriented thinking are regarded as threats to regional stability and autonomy. A successful campaign can be possible if Russia presents the “global majority” concept as a positive, inclusive, and cooperative initiative that is aimed at empowering Global South countries and upholding the principles of equal and mutually respectful multilateral engagement.

Secondly, Russia should aim to preserve the constructive core of the “global majority” concept, while at the same time, making it more acceptable to ASEAN in terms of its branding. Substantively, the “global majority” could be reinterpreted in the spirit of a “partnership for sustainable diversity.” This idea would emphasize diversity and equality, rather than numerical superiority. In this interpretation, Russia appears as one of the actors contributing to sustainable development, technological exchange, and mutual connectivity between both sides of the Eurasian and Indo-Pacific foreign policy spheres. Over time, this conceptual framework could be integrated into Russia–ASEAN documents, including the Comprehensive Plan of Action for the Implementation of the Strategic Partnership, the Strategic Cooperation Program, and joint statements.

Thirdly, Russian strategic concept needs to be pragmatized, with the most promising spheres for practical implementation lying in defense cooperation, energy, and agriculture. Integrating the notion of technological sovereignty into traditional defense partnerships with Southeast Asian states could reinforce Russia’s image as a reliable partner, one committed to technology sharing without imposing political conditions—a quality especially valued by ASEAN members, that prioritize maintaining strategic autonomy amid the influence of major powers.

Energy cooperation also represents a key area in which Russia can offer competitive solutions, ranging from the supply of hydrocarbons and the development of energy infrastructure to the implementation of joint projects in nuclear and green energy. Such an agenda could serve as a foundation for building long-term, mutually beneficial partnerships unburdened by rigid political commitments. It would also align with ASEAN’s guiding principle of “open regionalism,” which emphasizes inclusivity, flexibility, and non-exclusive cooperation among diverse foreign partners.

Cooperation in the agricultural sector and ensuring food security is no less important, as they are directly related to the sustainable development of the region. Russia already plays the role of a major grain and fertilizer supplier, which is particularly important for Southeast Asian countries given their growing populations and high dependence on foreign markets. Strengthening such ties could impart a tangible economic dimension to the “global majority” concept—customized for Southeast Asia—and transform it from a declarative idea into a practical instrument of cooperation.

The concept of the “global majority” has become one of the central elements of Russia’s new foreign policy rhetoric, reflecting Moscow’s intention to capture the transformations taking place on the world stage—the transition toward multipolarity, rise of the Global South, and the dismantling of the Western monopoly over the interpretation of international norms and institutions. Russia seeks not merely to position itself as part of the non-Western world, but to become one of the leading centers for the intellectual and political articulation of its interests. However, as the “global majority” concept gains traction among Russian official and expert circles, questions arise over the universality of this approach and its ability to resonate with foreign partners.

In this context, ASEAN presents an illustrative case—an association that over decades has developed its own model of regional interaction, grounded in the principles of consensus, inclusivity, and neutrality. As Russia explores new channels of dialogue with Asia and Southeast Asia, a dilemma emerges: can the mobilizing logic behind the “global majority” concept be reconciled with ASEAN’s pragmatic, consensus-driven, and institutionally grounded diplomacy? If so, to what extent can this concept be embedded within the political culture of Southeast Asian states without provoking tension or rejection?

Lost in Translation

Given that it is a relatively new concept, the notion of the “global majority” has yet to mature into a coherent political construct with a clear institutional logic and a conceptual framework that is clear to the targeted countries. At this stage, it operates largely as a symbolic framework that highlights the growing influence of the “collective non-West” and their demand for a more just world order. However, the conceptual ambiguity and ideological vagueness surrounding the concept limit its ability to extend beyond Russia and this limitation is common to all potential supporters of the concept. There are currently four underlying structural factors make it unlikely that Russia will be able to effectively project or institutionalize the “global majority” concept in Southeast Asia.

Reason 1. For Moscow, the “global majority” concept is not only a tool for symbolic consolidation with like-minded states in defense of sovereignty and cultural diversity, but also a means of positioning the West in opposition to the rest of the world. Any external framework that invokes a binary division between a “majority” and a “minority,” and that carries a pronounced geopolitical undertone, is likely to trigger unease within ASEAN as such a concept would be interpreted through the lens of bloc confrontation. From this perspective, openly endorsing the idea and identifying as part of the “global majority” would, in ASEAN’s view, represent a departure from its long-standing principles of non-alignment, strategic balance, and equidistance—effectively drawing the region into an undesirable confrontation with the United States and its Western allies. The loss—or even partial erosion—of the ability to pursue a multi-vector foreign policy, is a clear “red flag” for ASEAN. More broadly, the very emphasis on the term “majority” is likely to be perceived as artificial and overly politicized, running counter to ASEAN’s preference for a nuanced and diplomatic approach. These considerations underpin the Association’s cautious attitude toward initiatives such as QUAD and AUKUS, as well as its promotion of its own “depoliticized” version of the Indo-Pacific concept—one deliberately stripped of overtly anti-Chinese connotations.

Reason 2. Another challenge to the “global majority” concept in Southeast Asia stems from ASEAN’s institutional identity. For the Association, maintaining “ASEAN centrality” is of existential importance: it is around ASEAN that key regional dialogue platforms are organized, including the East Asia Summit, the ASEAN Regional Forum, the ASEAN Defense Minister Meeting Plus (ADMM+), and ASEAN+3, among others. Aligning too closely with Russia’s “global majority” framework risks undermining ASEAN’s agency and diminishing the political weight of the “ASEAN Ten.” Within such a framework, the Association would no longer function as the central hub, the primary institutional mechanism, or the agenda-setter of regional diplomacy. Instead, it would become merely one of many actors embedded within a broader ideological narrative. In other words, ASEAN would be viewed as just one component—albeit an important one—of a larger “majority,” whose key priorities are determined externally. Such a symbolic downgrade runs counter to ASEAN’s core principles and undermines its foundational philosophy: to play a central, agenda-shaping role in the evolving regional architecture.

Reason 3. Owing to their geographic position, institutional structure, and developmental priorities, ASEAN members tend to show limited interest in abstract geopolitical constructs. Their focus lies primarily on concrete areas such as trade, investment, technology access, and infrastructure development. For ASEAN, outside concepts only gain real traction when they are supported by realistic goals or linked to specific projects that promise clear and measurable benefits. A telling example is ASEAN’s engagement with China’s “Community of Shared Future for Mankind,” which many member states have endorsed through bilateral memoranda of understanding with Beijing. Importantly, this concept comes with substantial economic backing, most notably the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in which ASEAN countries are deeply involved. By contrast, Russia’s “global majority” framework currently lacks a comparable set of appealing economic initiatives. Without such a material dimension, the concept remains largely rhetorical and offers Southeast Asian states little practical incentive to adopt or institutionalize it.

A similar situation exists with another umbrella concept promoted by Russia—the Greater Eurasian Partnership (GEP). In nearly all major strategic documents and official statements, Russian policymakers consistently mention ASEAN as one of the key platforms and actors within this framework, alongside the EAEU, the SCO, and BRICS. From Moscow’s perspective, the creation of a broad Eurasian integration framework is inseparable from ASEAN’s participation, including the preservation of its central role, and the expansion of cooperation with Southeast Asian states. However, the concept—and even the term Greater Eurasian Partnership itself — does not appear in any official ASEAN documents or statements. One of the main reasons for this absence is the lack of clarity, at both official and expert levels, within ASEAN member states, about the goals and strategic intent of the GEP. Moreover, ASEAN members may view that the concept lacks a practical dimension—tangible projects or mechanisms that could deliver clear economic, strategic, or reputational benefits to the Association.

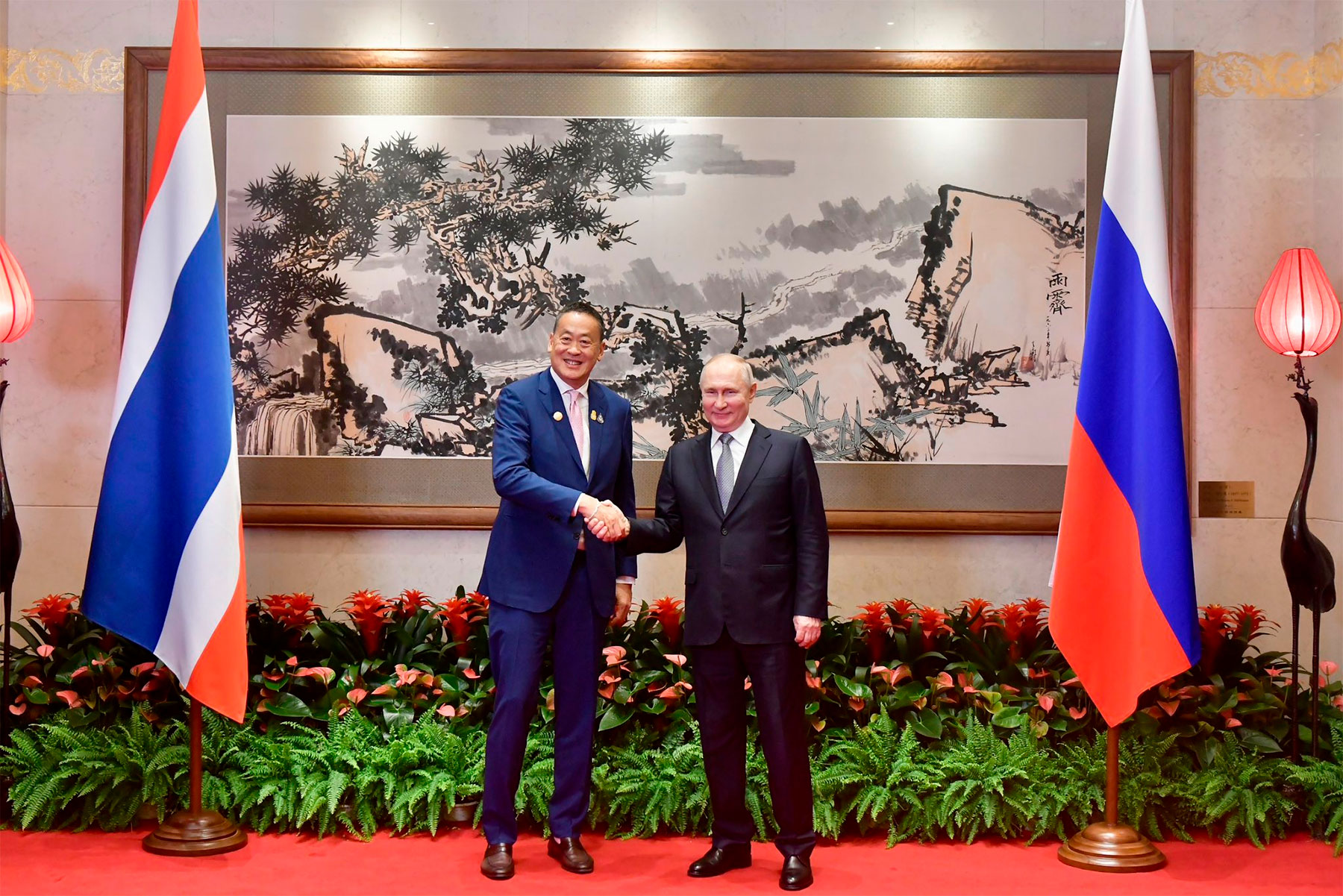

Reason 4. ASEAN is unlikely to reach internal consensus on the “global majority” concept because it directly contradicts the foreign policy orientations of several member states. Singapore, for instance, has openly condemned Russia’s actions in Ukraine and joined Western sanctions, resulting in Moscow adding the country to its list of “unfriendly states and territories.” Given these circumstances, it is inconceivable that Singapore—under significant Western pressure—would endorse or align itself with a Russian geopolitical narrative such as the “global majority.” The Philippines, while not having imposed formal sanctions or explicitly condemned Moscow amid the escalation of the Ukraine crisis, has nevertheless voted in favor of several “anti-Russian” resolutions at the UN General Assembly. Manila has consistently expressed support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and has condemned “the use of force to alter borders,” which can be interpreted as an implicit criticism of Russia. Notably, both the Philippines and Thailand are formal military and political allies of the United States. On many sensitive foreign policy issues, they are therefore compelled to coordinate their positions with Washington, further limiting their willingness or ability to publicly associate themselves with Russian-led geopolitical constructs such as the “global majority.”

Strategic Rebranding

Thus, attempts to promote the current “global majority” brand in Southeast Asia are unlikely to succeed. However, this does not preclude the possibility of successfully lobbying certain elements of the concept, provided they are carefully adapted for ASEAN countries.

First, it is necessary to reduce the ideological weight found in Russian discourse.

ASEAN countries are receptive to the idea of strategic autonomy; however, they prefer to frame it in neutral terms—equality, inclusiveness, and open regionalism. In this sense, they find non-confrontational, integrationist rhetoric acceptable, emphasizing interconnectedness, sovereignty, and the right to diverse paths of development without artificially dividing the world into “majority” and “minority.” In this regard, they embrace non-confrontational and integrationist rhetoric that underscores interconnectedness, sovereignty, and the right to pursue diverse paths of development, while rejecting any artificial division of the world into “majorities” and “minorities.” At the same time, the promotion of Russia’s “global majority” concept in Southeast Asia should not be framed as an explicitly anti-Western initiative or as a vehicle of geopolitical confrontation. Such framing would almost certainly provoke unease within ASEAN; bloc confrontation is viewed as a direct challenge to regional stability and strategic autonomy. For ASEAN member states, the preservation of strategic flexibility and the ability to maneuver among competing centers of power remain core principles of their foreign policy behavior. Accordingly, articulating the concept within an antagonistic narrative—“Russia and its supporters versus the West”—would not only erode its normative appeal, but foreclose opportunities for its institutionalization within regional frameworks. Conversely, the “global majority” concept stands a greater chance of success if Moscow presents it as a positive, inclusive, and cooperative framework—one oriented toward empowering the Global South, expanding opportunities all while supporting the principles of equal multilateral cooperation.

Second, it would be strategically sound for Russia to preserve the constructive essence of the “global majority” concept while rebranding it in a manner that resonates more effectively with ASEAN audiences. Substantively, the notion of a “global majority” could be reinterpreted through the lens of a “partnership of sustainable diversity”—an idea that underscores not numerical predominance, but the intrinsic value of diversity and equal mutual interaction. In this framework, Russia would be viewed not as a proponent of ideological confrontation with the West, but as a partner focused on fostering sustainable development, technological cooperation, and greater connectivity between the Eurasian and Indo-Pacific aspects of both sides’ foreign policy agendas. Over time, this concept could be institutionalized within Russia–ASEAN cooperation mechanisms, including the Comprehensive Plan of Action for the Implementation of the Strategic Partnership, the Strategic Cooperation Program, and future joint statements.

Third, Russian ideas require greater pragmatization. Without tangible results, even the most ambitious initiatives risk remaining declarative and failing to resonate within ASEAN’s policy frameworks. To gain real traction, the “global majority” concept must be operationalized through practical cooperation that aligns with the region’s concrete interests and development priorities. The most promising areas for such implementation in Southeast Asia include defense cooperation, energy, and the agricultural sector. In the defense domain—where Russia has traditionally maintained a strong foothold—Moscow has been one of the key arms suppliers to Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and several other states in the region. Embedding the notion of technological sovereignty within this existing framework could help reinforce Russia’s image as a reliable partner willing to share technology and refrain from imposing political conditions. This approach is particularly important for ASEAN member states, which are deeply protective of their independence from the great powers and value strategic autonomy.

Energy cooperation also represents a key sphere in which Russia can offer competitive and strategically relevant solutions, ranging from hydrocarbon supplies and energy infrastructure development to joint projects in nuclear and green energy. Such an agenda could serve as a foundation for building long-term, mutually beneficial partnerships unburdened by rigid political commitments. It would also align with ASEAN’s guiding principle of “open regionalism,” which emphasizes inclusivity, flexibility, and non-exclusive cooperation among diverse foreign partners.

Cooperation in the agricultural sector and ensuring food security is no less important, as they are directly related to the sustainable development of the region. Russia already plays the role of a major grain and fertilizer supplier, which is particularly important for Southeast Asian countries, given their growing populations and high dependence on foreign markets. Strengthening such ties could create a concrete economic dimension to the customized Southeast Asian “global majority” concept and transform it from a declarative idea into a practical tool for cooperation.