The Moscow–Tehran Axis: Alliance without Rigid Obligations

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |

RIAC Expert

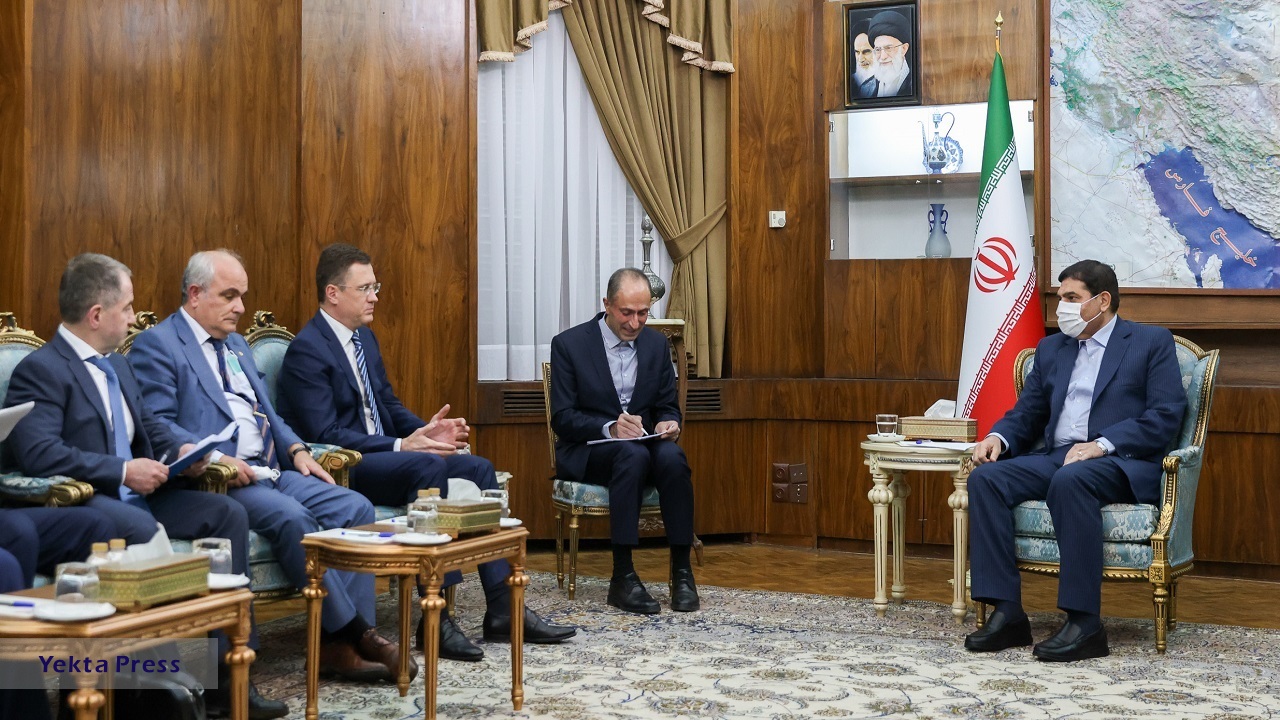

Russia and Iran are finding ever more points of convergence in their foreign policies and across the domain of economic cooperation. It is no coincidence that a record number of high-level visits between the two countries have taken place this year, the most recent being Vladimir Putin’s visit to Tehran to take part in the Syria summit of the leaders of Russia, Turkey and Iran.

Fostering relations with Iran, along with the continued functioning of the Astana Process, demonstrate Moscow’s increasing use of pragmatism in its foreign policy: any non-Western power is a welcomed partner, even if there are contradictions and inconsistencies in its relations with Russia.

With the relations with the West collapsed owing to the Ukraine crisis, Russia’s policy towards Iran is increasingly perceived as a policy case that could be heading in a promising direction. Putin’s trip to Iran did not bring any significant breakthroughs, although news reports about the summit and events surrounding it were overwhelmingly positive. One newsworthy item, for example, was the launch of the rial/rouble pair on the Tehran Currency exchange on the day of the summit, while another was a memorandum signed between National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) and Gazprom to involve investments of approximately $40 billion into Iran’s oil sector.

It must be noted here that there is no guarantee that all these initiatives will be successful in the end. For one, timelines have not been set out for most of the projects, and not all of them will even reach the stage of implementation. And those that do—for example, the supply of aircraft parts—will concern a limited set of products.

The bunch of contradictions that has accumulated in Russia–Iran relations does not stand in the way of rapprochement between the two countries. Russia is realistic in its approach, and this makes it possible to focus on areas of common interest, even when there are far more problems in bilateral relations, for example in Moscow’s relations with Ankara. At the same time, both Moscow and Tehran are extremely interested in an alternative to the West-dominated economic order. Neither country can do this alone, but these two “political outcasts” countries are better suited to the task than anyone else.

Here, positive developments were reflected in the conclusion of a long-term strategic agreement between Russia and Iran similar to the documents that Tehran signed with China and Venezuela. Judging by what Russian officials said, the project will be finalized quite soon. Importantly, the agreement will take the form of a memorandum—a formal confirmation that the intentions do not impose any direct obligations on the two countries. The “Russia–Iran axis” will continue to move in more or less the same direction. Relations between the two countries may well expand and deepen with each passing year to never-before-seen levels, but the sides harbor no intention of taking any unwanted obligations, including becoming allies.

Russia and Iran are finding ever more points of convergence in their foreign policies and across the domain of economic cooperation. It is no coincidence that a record number of high-level visits between the two countries have taken place this year, the most recent being Vladimir Putin’s visit to Tehran to take part in the Syria summit of the leaders of Russia, Turkey and Iran.

Fostering relations with Iran, along with the continued functioning of the Astana Process, demonstrate Moscow’s increasing use of pragmatism in its foreign policy: any non-Western power is a welcomed partner, even if there are contradictions and inconsistencies in its relations with Russia.

Biden in the Background

The Astana summit and Putin’s visit to Tehran came immediately after U.S. President Joe Biden’s tour of the Middle East. Despite numerous commentators suggesting that the Russian leader’s visit to Iran was a “response” to the initiative of the American president, there is no real substance to this argument. What Biden’s trip does do is place the trilateral meeting in the Iranian capital into a wider context.

The Middle East is one of those regions where the presence of the United States and Russia matters, although the dynamics of their engagement are diametrically opposed to one another. While Washington is gradually pulling out of the region that holds less and less allure for the White House, Moscow is doing exact the opposite, being increasingly pulled into the processes unfolding in the Middle East.

The basic approaches of the two sides differ as well. The United States has become accustomed to finding allies in the region so that they can become conductors of its policy, while at the same time looking for key troublemakers that it can try to contain and isolate. Russia, on the other hand, does not have friends or enemies in the region. Over the past decade, Moscow has been trying to act as a universal mediator, maintaining relations with all the key forces in the Middle East.

Against the backdrop of the events in Ukraine, the United States has set about trying to turn Russia into an international pariah. Moscow sees the Middle East as a possible route to circumventing the sanctions, even if partially, so it is only logical that Washington would seek to isolate Russia in the region. This is proving somewhat difficult, however, even with its impressive list of allied states and the lukewarm reaction of Middle Eastern countries to Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine. For one thing, no one in the Middle East wants to be faced with a choice between Moscow and Washington. In the Middle East, Russia remains a player to be reckoned with, and its interests coincide with those of almost all the countries in the region—including Washington’s partners—on a whole range of issues.

Take Turkey, for example, a NATO member who has serious disagreements with Russia over Syria, Libya and the South Caucasus. Worse still, Ankara has openly criticized Moscow’s actions in Ukraine, lending active support to Kiev by supplying hi-tech weapons. At the same time, Turkey, much as Russia, does not hide its annoyance at the U.S.-established order in the regions adjacent to its territory, notably the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean. Let’s not forget Russia–Iran trade relations as trade turnover between the two amounted to some $33 billion in 2021 and the bilateral trade is expected to reach even greater heights by year-end 2022. Given this, Ankara will clearly want to continue dialogue with Moscow, both with regard to Syria and on other issues.

A somewhat similar situation has been the case for the Arab countries in the Persian Gulf. Not a single one of these has joined the Western sanctions against Russia, and the United Arab Emirates is turning into something of a hub for Russian capital. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has made it clear that his country places its agreements with OPEC+, where Russia is a key player, above U.S. interests, and Joe Biden’s visit did nothing to change this.

Outside the Persian Gulf, President of Egypt Abdel Fattah El-Sisi has also refused to pursue a policy to isolate Moscow. Cairo has been one of the biggest importers of Russian weapons in recent years. And, like the United Arab Emirates, the country is also cooperating with Russia on Libya. Finally, there is another important U.S. partner, namely, Israel. Despite some friction with Moscow, Tel Aviv is still willing to cooperate with Russia to sustain its policy of containing the Iranian threat in Syria. In other words, all these players have more than enough reason to turn their backs on the binary approach that Washington imposes on them, where they are forced to choose between the United States and Russia.

The Astana Model

It would be quite a mistake to dub Joe Biden’s tour of the Middle East a complete failure. He got some wins here and there, such as the Saudi decision to open flights to and from Israel. Besides, it is unlikely that the U.S. was harboring any real hopes to reverse the regional alignment, including the attitudes towards Russia, all in a single trip. What is telling here is the situation as such. The events in Ukraine were indeed a turning point in relations between Moscow and the West—however, the Middle East did not undergo any major changes until February 24, 2022, and later.

Today, the situation in the region is much different to the Cold War-style polarization that analysts bring up so frequently. The Middle East of 2022 is a complex combination of multi-vector approaches of various countries. All this is not so much a reflection of Washington’s weakness as it is an illustration of the fact that Russia continues to be an important and legitimate player for Egypt, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Israel and the United Arab Emirates, and this is unlikely to change any time soon.

It is this difficult political climate that gave rise to the Astana format, a platform where the parties with different approaches—and even waging a proxy war against each other—can come to the negotiating table as partners who resolve issues. True, this format may only have worked in relation to the Syrian dossier in years gone by, but the most recent summit took the paradoxical relations between the countries to a new level. Turkish drones carry out targeted attacks on the Russian Army, which in turn shoots them down. But this did not prevent Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdogan from sitting at the same table and having a constructive conversation at the meeting in Tehran. Moreover, one of the main topics on the summit’s side-lines did not even have anything to do with the region, and that was finding a solution to the issue of exporting grain through the Black Sea.

This has nothing to do with banal hypocrisy on the part of sides with opposing interests. The participants in the Astana summit were not hiding behind smiles, sticking their middle finger up at each other from inside their pockets… no, they held a constructive dialogue. The grain issue was eventually resolved thanks to the negotiations between Turkey and Russia, and the summit in Tehran was largely responsible for getting the two together in the first place.

The Astana summit is swiftly turning into a model that reflects the basic principles of Russia’s foreign policy. What this model essentially boils down to is political realism in its purest form, where everyone is invited to cooperate, regardless of accumulated problems and disagreements, assuming the sides have overlapping interests.

And the invitation has effectively been extended to the West: despite the proxy conflict waged between Europe and Russia on the Ukrainian soil and despite the economic war in the form of sanctions, Moscow is nevertheless prepared to sell oil and gas to Europe. “Gazprom has always fulfilled and will continue to fulfil its obligations in full. If that’s what European countries want, of course, as they are the ones closing the pipes,” Vladimir Putin noted calmly at a press conference following the Tehran summit.

At the same time, the Astana format stands at odds with the traditional integration models of the West, which believes similar values to be a prerequisite for alliances. Certainly, the Americans do not always follow this approach. Still, even those relationships where common values typically play little if any role—such as that between the United States and Saudi Arabia—become bogged down by human rights issues (in this case, Biden’s condemnation of the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi). In the present situation, we see that the Astana model of radical realism allows Russia, in such a difficult situation, to pursue dialogue with all players in the Middle East, while the United States is facing problems talking to its traditional allies.

Engaging Iran

With the relations with the West collapsed owing to the Ukraine crisis, Russia’s policy towards Iran is increasingly perceived as a policy case that could be heading in a promising direction. Putin’s trip to Iran did not bring any significant breakthroughs, although news reports about the summit and events surrounding it were overwhelmingly positive. One newsworthy item, for example, was the launch of the rial/rouble pair on the Tehran Currency exchange on the day of the summit, while another was a memorandum signed between National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) and Gazprom to involve investments of approximately $40 billion into Iran’s oil sector.

Some important news came out shortly after the Russian President’s visit, such as the decision to increase the number of flights between Russia and Iran up to 35 per week, or the announcement that an agreement on the supply of aircraft parts and maintenance work was being drawn up, or plans to earmark $1.5 billion for the development of railway projects in Iran.

It must be noted here that there is no guarantee that all these initiatives will be successful in the end. For one, timelines have not been set out for most of the projects, and not all of them will even reach the stage of implementation. And those that do—for example, the supply of aircraft parts—will concern a limited set of products. The Iranian aviation industry has been in a rut for a number of years now, thanks to the sanctions. They have learned to make certain things on their own, sure, but most parts are either imported through third countries or stripped from old planes that no longer fly.

Despite all this, some projects might turn out to be rather successful. The number of areas where cooperation between the two countries is possible is clearly expanding, and this is thanks to the sudden spike in interest on the Russian side in Iran. In addition to this, traditional pockets of cooperation are getting a new push. For example, the export of Russian agricultural products against the backdrop of the global food problem is fast becoming a key element of Iran’s food security. And the North–South Transport Corridor, which has been operating in test mode for the past few years, could very well become the main export route for Russian products.

A certain rapport can also be witnessed in the domain of foreign policy. Iran’s reaction to the events in Ukraine was more positive than that of the other Middle Eastern states. During his meeting with Vladimir Putin in Tehran, the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, stressed that NATO would have started a war with Russia on the pretext of Crimea if it had not been stopped in Ukraine. Certain changes can also be seen in Syria, where Russia’s responses to the actions of Israel are becoming increasingly harsh. Finally, the hallmark of the trilateral summit in the Iranian capital was the attempt of Tehran and Moscow to convince Ankara to abandon its military operations in Syria.

Be that as it may, there is no way the alignment between Russia and Iran would turn into a full-fledged alliance. The main reason why this will never happen is because of Russia’s image in Iran, which is riddled with negative historical connotations. Distrust of Tehran and a poor understanding of its policies can be found among the Russian elite as well. Besides, the sides disagree quite strongly on a number of issues, including their respective policies in the Middle East and how to resolve the territorial disputes over the Caspian Sea.

Also keep in mind that Russia and Iran are competitors in the energy market. The agreement with Gazprom largely stems from Russian efforts to gain leverage over the Iranian oil and gas industry. Exactly how much leeway the Iranian side will give to Russian companies remains to be seen.

Russia and Iran in Syria: A Competitive Partnership?

***

However, paradoxical as it may sound, the bunch of contradictions that has accumulated in Russia–Iran relations does not stand in the way of rapprochement between the two countries. Russia is realistic in its approach, and this makes it possible to focus on areas of common interest, even when there are far more problems in bilateral relations, for example in Moscow’s relations with Ankara. At the same time, both Moscow and Tehran are extremely interested in an alternative to the West-dominated economic order. Neither country can do this alone, but these two “political outcasts” countries are better suited to the task than anyone else.

Here, positive developments were reflected in the conclusion of a long-term strategic agreement between Russia and Iran similar to the documents that Tehran signed with China and Venezuela. Judging by what Russian officials said, the project will be finalized quite soon. Importantly, the agreement will take the form of a memorandum—a formal confirmation that the intentions do not impose any direct obligations on the two countries. The “Russia–Iran axis” will continue to move in more or less the same direction. Relations between the two countries may well expand and deepen with each passing year to never-before-seen levels, but the sides harbor no intention of taking any unwanted obligations, including becoming allies.

(votes: 1, rating: 5) |

(1 vote) |