It would naïve to expect that, with a declared war of sanctions on Russia, the West will refrain from throwing up barriers in the way of Russia. The West will certainly use negative publicity, political pressure, manipulating the requirements for grain quality (for instance, setting ergot content requirement at zero or near-zero, which caused Egypt to reject as defective some of the wheat exported from Russia in 2018). Some international bodies may, using the external restrictions as a pretext, deny funding to Russia’s humanitarian deliveries to curry favor with the Western rivals.

Amid the emergency environment of hostile sanctions, Russia will need to devise a comprehensive approach to expanding its foreign trade with the Arab world, which means introducing new and efficient mechanisms, such as payments in national currencies and clearing payments. They could be used in trade relations with Egypt, Morocco and Algeria, where Russia shipped 60,000 tons of its wheat in June 2021, after a five-year hiatus. It would primarily be expedient to use these countries’ interest in increasing the exports of their own agricultural products to Russia (citrus cultures, seasonal vegetables).

The markets of the solvent Arabian Peninsula are of interest, too. Here, Russia has achieved certain succes. Should mutually beneficial agreements on a broad range of cooperation be in place, including deliveries of Russian cutting-edge technologies, the members of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf could, as an option, fund expanded humanitarian deliveries of the Russian wheat to Yemen, Syria, and Libya.

We should recognize Russia’s promising ability to play a more active role in ensuring food security in the nations of the Middle East and North Africa. This would solve the priority tasks of supporting Russian agrarians and acquiring additional sources of revenue for Russia’s treasury.

When on March 12, Denis Shmygal, Ukraine’s Prime Minister, announced that a prohibition or severe restrictions would be imposed on exports of wheat, buckwheat, eggs, oil, sugar, and other foods, his message produced no sensation, given Ukraine’s largely paralyzed agrarian sector. Military action has disrupted economic, transportation and logistical connections, restricting navigation in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea (the leading Azov port of Mariupol is not functioning, while, Ukrainian authorities have fully or partially shut down the ports of Kherson, Nikolaev, Odessa, Izmail, among others, since February 25). Despite Kiev’s assurances concerning state support for agricultural manufacturers, Ukrainians should hardly be expected to start sowing on time in 2022, not to mention resuming full-fledged exports in the foreseeable future.

On the other hand, it is fairly difficult to say what impact the toughened anti-Russian sanctions will have on Russia’s agricultural market and its agricultural exports. This uncertainty, combined with the desire to prevent price gouging on the global market, has forced the Russian government on March 14 to prohibit exports of wheat, rye, their mixture (maslin), barley, corn into the countries of the Eurasian Economic Union until June 30, 2022, and exports of sugar into third countries until August 31.

Even before Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, FAO experts estimated that decreasing crops had a negative effect on the turbulence on the global grain market, and Russia’s and Ukraine’s dominance in wheat sales have become an additional factor. In 2020, according to FAOstat, Russia was the largest exporter of wheat (USD 7.92 bn.), emerging ahead of the U.S. (USD 6.32 bn.), Canada (USD 6.3 bn.) and France (USD 4.5 bn.). Ukraine was the fifth-largest exporter (USD 3.59 bn.). Russia and Ukraine together, therefore, accounted for some 30.5% of total sales. Besides, Ukraine was the largest exporter of corn (according to UN Comtrade, its total exports in 2016–2020 were USD 15 bn., as compared to Russia’s USD 3 bn.).

It is therefore far from surprising that the price for a ton of food-grade wheat at MATIF, the Paris Futures Exchange, spiked from EUR 197.25 as of July 9, 2021 first to EUR 265 (February 17, 2022), followed by the record EUR 396.5 a few days later (March 7). Many analysts have expressed their reasonable concerns that the ongoing Ukrainian crisis could produce inflation and other consequences, whose impact would be even greater than that of the 2008 Great Recession. It would be pertinent to quote Gilbert Houghbo, President of the International Fund for Agricultural Development, who was warning about a possible hike in food prices as well as about a famine—something, he argues, threatens food security globally, bolstering geopolitical tensions.

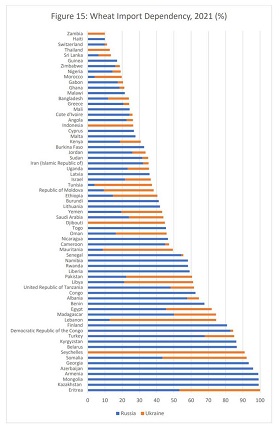

The Arab nations of the Middle East and North Africa end up in the risk group, particularly those having vast populations (Egypt – 106 million people; Algeria and Sudan – 45 million people each), those involved in armed conflicts (Yemen, Libya, Syria, the area of the Israel-Palestine conflict), those engulfed by a domestic crisis (Lebanon) or those facing an unstable political situation domestically (Iraq).

As much as in the countries plagued by problems, the elites of the relatively prosperous nations, such as Jordan, are increasingly apprehensive of the prospects for domestic political stability following an influx of 674,000 refugees from Syria (as of February 28, 2022), as the authorities fear that food riots under the slogans of the “Arab spring” could quite be possible. In the Kingdom of Bahrain ruled by the Sunni Al Khalifa dynasty, an unexpected spiral of food inflation may cause unrest among the local Shia majority, as it happened in February–May 2011.

Leaders of the Arab nations never forgot that the initiators and participants of the first wave of protests in 2011–2012 demanded both freedom and bread. The main slogan of the “Jasmine Revolution” in Tunisia was “Bread, Water, and No Ben Ali [Tunisia’s President – I.M.].” Given that Tunisia’s food security used to depend directly on deliveries of the Ukrainian wheat (USD 242 million in 2019 and a total of USD 770 million in 2016–2020), a simultaneous cessation of deliveries can indeed be fraught with an outbreak of social discontent.

According to UN Comtrade, Egypt, the region’s largest importer, purchased wheat for USD 7.39 bn. in Russia and for USD 2.34 bn. in Ukraine in 2016–2020. In 2019 alone, out of the total deliveries worth USD 3.02 bn., Russian deliveries totaled USD 1.44 bn., while Ukrainian deliveries totaled USD 773.4 million. This suggests that the two countries accounted for 73% of Egypt’s imports. Today, given the market’s volatility—owing to both the operation in Ukraine and toughened anti-Russian sanctions imposed by the West—Egypt faces an acute deficit of offers: GASC, the national supply agency, was forced to cancel the announced bidding on February 24, with deliveries between April 11–21, 2022, since only one offer had been submitted. In the coming days, Cairo will apparently have to take prompt measures to diversify its deliveries in order to avoid an appreciable deterioration in its food security.

Having lost stable wheat imports from the Black Sea region, Algeria’s state grain agency, the OAIC, is also considering an option of expanding its supplier geography. There are talks of allowing imports of French wheat, which had been prohibited since October 2021 over the scandal prompted by Emmanuel Macron’s negative statements accusing Algerians of re-writing the history of their colonization.

Issues of food security are quite tough in the territories controlled by the Palestinian National Authority (out of total deliveries of wheat USD 10.98 million worth in 2020, Russia accounted for 9.18 million, which is 83%) as well as in Lebanon, a country that, as the UK’s Crown Agents reports, imported 67% up to 95% of its grain in 2010–2018 from the Black Sea region. In 2010–2017, Russia was the principal exporter, while the leadership went over to Ukraine in 2018–2019 (with the exception of 2013, when Romania was the second-largest exporter). In 2021, Lebanon purchased 630,000 tons of wheat, of them 520,000 tons originated from Ukraine, with the rest coming from Russia, Moldova, and Romania. Therefore, amid a protracted domestic crisis and inexorable increase in prices on virtually all goods, a common Lebanese citizen was predictably facing a rapid and acute shortage of bread and flour once Ukrainian deliveries ceased.

However, the situation was the hardest in the countries going through domestic armed conflicts and frequently unable to fund commercial food deliveries. For instance, the UN reports that in 2019, out of the total imports of nearly USD 550 million, Yemen imported USD 145.8 worth of wheat from Russia (26.5%) and USD 79.8 million worth of wheat from Ukraine (14.5%). Accordingly, WFP’s executive director David Beasly did not rule out the possibility of the situation in Yemen’s food security deteriorating catastrophically in the nearest future. Things are not much better in Libya, a country ravaged by the civil war: amid the developments in Ukraine, the prices of bread and flour went up by 40%, while oil prices went up by 25%. In Iraq, bread and sugar prices increased by some 20%. Even though Syria’s Prime Minister Hussein Arnous assured on March 14 that wheat supplies would be sufficient to last until the next harvest, the situation in the country is still highly equivocal, owing to disrupted economic ties (the Trans-Euphrates region, long considered Syria’s “breadbasket,” is still controlled by the Kurds), devastation, and sanctions.

Can Russia save the Arab world from food riots? This is not a rhetorical question. Moscow appears to have a real potential to boost its exports to the Middle East. For instance, in January–July 2021, Russia succeeded in ramping up its agricultural exports to Tunisia by 4.5 times, as compared to the same period of 2020—in monetary terms, there was a sixfold increase, up to USD 112 million. Russia’s agricultural food-grade 3rd and 4th class wheat is quite competitive on the global market, as it is good quality grain sold at reasonable prices.

It would naïve to expect that, with a declared war of sanctions on Russia, the West will refrain from throwing up barriers in the way of Russia taking over the niche of Ukrainian exporters. The West will certainly use negative publicity, political pressure, manipulating the requirements for grain quality (for instance, setting ergot content requirement at zero or near-zero, which caused Egypt to reject as defective some of the wheat exported from Russia in 2018). Some international bodies may, using the external restrictions as a pretext, deny funding to Russia’s humanitarian deliveries to curry favor with the Western rivals.

Amid the emergency environment of hostile sanctions, Russia will need to devise a comprehensive approach to expanding its foreign trade with the Arab world, which means introducing new and efficient mechanisms, such as payments in national currencies and clearing payments—something the USSR successfully used in its trade with India. They could be used in trade relations with Egypt, Morocco and Algeria, where Russia shipped 60,000 tons of its wheat in June 2021, after a five-year hiatus. It would primarily be expedient to use these countries’ interest in increasing the exports of their own agricultural products to Russia (citrus cultures, seasonal vegetables).

The markets of the solvent Arabian Peninsula are of interest, too. Here, Russia has achieved certain success: the Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Supervision (Rosselkhoznadzor) reports that Russia shipped 916,000 tons of wheat to Saudi Arabia as of January 17, 2022, in the current agricultural year (2021/2022), a figure six times higher than that of 2020/2021. Between July 1, 2020 and January 13, 2022, the Saudis imported 2.9 million tons of barley. Should mutually beneficial agreements on a broad range of cooperation be in place, including deliveries of Russian cutting-edge technologies, the members of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf could, as an option, fund expanded humanitarian deliveries of the Russian wheat to Yemen, Syria, and Libya.

To recap. We should recognize Russia’s promising ability to play a more active role in ensuring food security in the nations of the Middle East and North Africa. This would solve the priority tasks of supporting Russian agrarians and acquiring additional sources of revenue for Russia’s treasury.