Interview

The strategic importance of Central Asia and its vast energy resources draw a lot of external interest to it. Russia traditionally has been the strongest outside player in in the region. But now China’s active involvement in energy sector of Central Asia is quickly increasing its influence and challenging Russia’s position in the region. In this interview Dr. Robert M. Cutler, Senior Research Fellow in the Institute of European, Russian & Eurasian Studies at Carleton University discusses the issues of China-Russia competition and cooperation in the context of energy security in Central Asia.

Interviewee: Dr. Robert M. Cutler, senior researcher at the Institute of European, Russian and European Studies, Carleton University, Canada.

Interviewer: Maria Prosviryakova, Russian International Affairs Council.

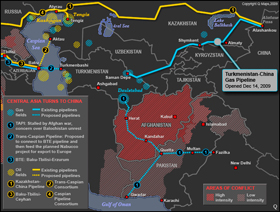

China’s influence is growing rapidly in Central Asia. Thus, the Central Asia-China gas pipeline was open in 2009. China built strong ties with Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. Why is it that cooperation with China appeals to these countries of Central Asia?

It is slightly different in the two cases that you mention. Turkmenistan's President Saparmurat Niyazov signed the agreement for a Turkmenistan-China pipeline in April 2006. Construction began slowly the next year, but Turkmenistan turned more definitely towards China following a 2009 pipeline explosion for which Moscow and Ashgabat blamed one another. After Gazprom insisted on a new pricing structure, no gas went from Turkmenistan to Russia for many months.

The new President of Turkmenistan, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, accelerated the search for other export partners. About this time, the first of several audits of Turkmenistan's gas reserves, executed according to international accounting standards, by the British firm Gaffney, Cline & Associates, was published, showing enormous new quantities in the South Yoloton (Galkynysh) gas field. With Chinese technical assistance and funding, the 1,833 kilometer long pipeline was built in 28 months. Planned gas exports from Turkmenistan to China rose quickly from 10 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/y) to 30 bcm/y and later 60 bcm/y. These levels are yet to be approached, but the laying of more lines of parallel pipes along the same route is under way.

Kazakhstan is geographically closer to China and therefore more subject to geo-economic influence. China's presence in Kazakhstan's energy sector is of longer duration and also more deeply entrenched than is the case in Turkmenistan. In the privatizations in the 1990s, China acquired energy enterprises in the west of Kazakhstan and took financial losses there for years, simply in order to maintain a presence on the ground. In the late 1990s a contract was signed to construct an oil pipeline from eastern Kazakhstan into China. Negotiations over the implementation of this project delayed its execution for a number of years, but in December 2005, this Atasu-Alashankou oil pipeline was opened, entering into service the following year. This oil pipeline was extended westward to the Caspian Sea piece-by-piece, roughly tripling in length as China purchased a Canadian company that owned a segment it needed in central Kazakhstan, while its presence in the western part of the country since the 1990s allowed another segment to be added on to those further east. The gas pipeline from Turkmenistan to China passes through Kazakhstan as well, and it will carry Kazakhstani gas for export in later stages.

How likely is it that China will eventually take over Russia in Central Asia? Under what circumstances can this happen?

China today has many more energy options besides Russia than it did even as recently as five years ago. China's energy balance-sheet as well as its foreign investment strategy will continue to drive it to do whatever is necessary to help the Central Asian countries to develop their energy resources for export, especially to China. With capital from China there will come Chinese workers and methods of industrial organization, as has already happened in parts of Kazakhstan. These developments will lead, in turn, to an anchoring of Chinese political-economic influence in the Central Asian region over the long term, not only in Kazakhstan but also beyond.

Russia will nevertheless remain the principal military-strategic power in the region, thanks in part to the institutionalization of the CSTO, to which China does not belong. There is some military cooperation between Kazakhstan and China, but Russia remains Kazakhstan's principal source of arms.

The Central Asian states are sometimes referred to as passive observers of the fight for their resources. Nevertheless, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan become increasingly independent relying on “multi-vector” energy policies. Do you believe that this also could be the best strategy for other countries in the region?

In principle, yes, insofar as it is possible. From the standpoint of energy-consuming countries energy security means security of supply. From the standpoint of energy-producing countries, however, energy security means security of demand. It is natural that any energy-producing country should want to have multiple customers, just as any energy-consuming country should want to have multiple suppliers.

It is worthwhile to note that Kazakhstan is perhaps the first in the region to use the term “multi-vector policy”. Kazakhstan used it in connection with its basic foreign-policy (not just energy) orientation as soon as the early 1990s. This was due not just to the geographic centrality of Kazakhstan in Central Asia but also to its situation as having a relatively small population that is distributed over a large surface area, with hardly any juridical state borders that might coincide with naturally defensible geophysical features. In time, it became applied to energy export directions in particular.

The desirability of a multi-vector energy policy for Turkmenistan has already been discussed above. China is not the only direction. Berdimuhamedow's serious interest in the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP) dates also from the months following the diplomatic fiasco around the 2009 pipeline explosion. Also, in May 2010 he made his first trip to India to have discussions about the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline project. Separately, the United Arab Emirates, through its sovereign wealth fund using Dubai-based Dragon Oil, was at about this time admitted to the country to bid on offshore exploration rights.

By contrast, Uzbekistan remains relatively ensconced in the exclusively Russian energy sphere. Gazprom's subsidiary Zarubezhneftegaz remains very important in Uzbekistan. South Korea and Malaysia are two of the few other foreign countries whose firms participated in energy exploration and development in Uzbekistan, in its search to escape exclusive dependence on Russian technical assistance. Uzbekistan has also been trying to develop Uzbekneftegaz as its own “national champion”. Almost all of Uzbekistan's gas exports go to Russia, but the country has been trying to diversify its customers, for example by cooperating with the Chinese company CNPC on the Uzbekistani segment of the Turkmenistan-China pipeline.

Uzbekistan has been supplying Tajikistan also but this will change as Gazprom is helping to explore a domestic gas field in Tajikistan estimated to be worth 50 years of domestic consumption. Southern Kazakhstan will soon no longer be dependent on gas from Uzbekistan as the Turkmenistan-China pipeline, which runs through Shymkent, kicks into gear. China has paid less attention to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, because they are smaller countries and less important strategically. It has nevertheless gained significant influence over Kyrgyzstan, although the energy sector has had little to do with this. Kyrgyzstan concentrates its energy development in the hydroelectric sector, using the resultant electricity domestically and exporting some of it to China and Russia. Kyrgyzstan has been seeking to decrease its dependence on imports of gas from Uzbekistan.

Some experts believe that Central Asia may be the apple of discord between Russia and China. Do you agree with this? And if so, then what can be done to improve their energy cooperation in the region? What joint projects could they work on?

Russian and Chinese energy companies have had minor disagreements over Central Asian resources, but I am not certain that Central Asia represents an apple of discord between Russia and China. As for cooperation between them in Central Asia, I do not see why any Central Asian country should wish to encourage them to cooperate. Certainly, the countries in the region have better reason to encourage competition between them. According to simple market logic, they have better chances of getting better deals that way.

From the standpoint of energy alone, Central Asia is not the main “playing field” for Russia-China cooperation anyway. The stakes in Siberia and the Arctic region are much greater. That is where they have been discussing joint projects, because the energy resources are there are more challenging but with higher potential return than they are in Central Asia. Russia is an energy producer and China is an energy consumer. Why should Russia help the Central Asian countries to develop their own resources for export to China? That would only be creating market competition for Russia itself. But also, as the example of Turkmenistan shows, Russia cannot prevent them from working with China if they wish to do so.

In this connection, it is worthwhile to mention that neither China nor Russia has successfully put any real effort into multilateral energy cooperation inside the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), because the SCO does not offer to either of them any advantage that they cannot pursue themselves individually, bilaterally with third countries. This failure of genuine multilateralization is characteristic in general of the SCO, which is a geostrategic symbol and platform for diplomatic and expert-level meetings, but which has achieved no real autonomy or momentum of its own as a self-standing organization.

The United States and the European Union are very concerned about Russia-China energy cooperation. The EU is concerned that its own energy security can be affected. The US is concerned that such cooperation can turn into strategic alliance between Russia and China. Will the US and EU energy policies in Central Asia be able to hinder energy cooperation between Russia and China in the long run?

Russian and Chinese energy cooperation projects are directed by state policy even if they are not always executed by state enterprises. Russia and China already have the basis for a strategic partnership through the bilateral 2001 treaty, which was the first treaty that they had signed in 50 years. As such, there is relatively little that the EU and the US can do about the bilateral energy cooperation. Its success or failure will be the product of the interests of the respective countries, and how those interests are expressed. Questions about prices and transportation have presented difficulties for the conclusion of Russian-Chinese agreements, and there is no reason why this should change in general, even if progress is made on individual projects.

China will therefore continue to deepen its energy relations with the Central Asian states. The EU and US energy policies themselves are affected by Russian policy and by Chinese policy but not so much by cooperation between them, except outside Central Asia. The EU does not have the diplomatic weight to promise very much, in the eyes of the countries in the region. Also, it is important not to confuse the EU with the major energy companies that are headquartered in its various member-states. The EU cannot tell them what to do, and they are free to disregard the “indicative” recommendations from Brussels insofar as their activities outside the borders of the EU are concerned.

Dr. Cutler, thank you so much for the interview.