Nuclear Terrorism: Bogeyman or Real Threat?

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Ph.D. in History, Senior Researcher at SIPRI, RIAC Expert

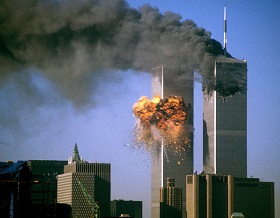

In early July 2013, Vienna hosted an international conference on nuclear security that culminated in a declaration stating that IAEA countries “remain concerned about the threat of nuclear and radiological terrorism and of other malicious acts or sabotage related to facilities and activities involving nuclear and other radioactive material”. Despite the substantial progress made in recent years in strengthening nuclear security worldwide, the document notes, more needs to be done in this field. The declaration suggests that numerous states need to pay greater attention to the threat of nuclear terrorism, which shows no signs of going away, and instead is only becoming more tangible.

In early July 2013, Vienna hosted an international conference on nuclear security that culminated in a declaration stating that IAEA countries “remain concerned about the threat of nuclear and radiological terrorism and of other malicious acts or sabotage related to facilities and activities involving nuclear and other radioactive material”. Despite the substantial progress made in recent years in strengthening nuclear security worldwide, the document notes, more needs to be done in this field. The declaration suggests that numerous states need to pay greater attention to the threat of nuclear terrorism, which shows no signs of going away, and instead is only becoming more tangible.

Theory and Practice

Under the International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism adopted by the UN General Assembly on 13 April 2005, a person is deemed to have committed a crime qualified as an act of nuclear terrorism if that person:

- Possesses radioactive material or makes or possesses a device:

- With the intent to cause death or serious bodily injury; or

- With the intent to cause substantial damage to property or to the environment;

- Uses in any way radioactive material or a device, or uses or damages a nuclear facility in a manner which releases or risks the release of radioactive material:

- With the intent to cause death or serious bodily injury; or

- With the intent to cause substantial damage to property or to the environment; or

- With the intent to compel a natural or legal person, an international organization or a State to do or refrain from doing an act.

Under the Convention, threats to commit an offence as set out above, unlawful or intentional demands relating to radioactive materials, devices or nuclear facilities, or participation in and contribution to the commission of an act of nuclear terrorism are all qualified as nuclear terrorism.

Acts of nuclear terrorism can be linked to attempts to build or acquire, first, a nuclear explosive device, and, secondly, radiological weapons (i.e. a ‘dirty bomb’), giving rise to nuclear or radiological terrorism, respectively.

The most infamous instances of nuclear terrorism have included attempts made by Al-Qaeda, the Japanese cult of Aum Shinrikyo, and Chechen terrorists, to acquire nuclear weapons or related components and technologies. According to the US, late Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden had been engaged in such attempts since 1992.

Instances of nuclear terrorism in Russia are all linked to Chechnya. In an interview with Komsomolskaya Pravda on 21 October 1995, Shamil Basayev alleged that he had enough radioactive material to stage a few “mini-Chernobyls”.

The Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo, also showed interest in acquiring nuclear weapons; according to a former FSB officer, its agents paid visits, among others, to the Kurchatov Nuclear Research Centre, Zhukovsky Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI), and the Atomic Energy Institute in Russia. Invited by the cult, about a dozen scientists from a number of Russian research establishments left the country allegedly to become involved in projects aiming to create weapons of mass destruction (WMD) [1]. However, Aum Shinrikyo’s efforts failed, and the cult stopped trying [2].

Overall, acts of nuclear terrorism can be linked to attempts to build or acquire, first, a nuclear explosive device, and, secondly, radiological weapons (i.e. a ‘dirty bomb’), giving rise to nuclear or radiological terrorism, respectively.

DIY

Nuclear terrorism involves using fissile weapons-grade materials: Uranium-235 enriched to over 90% and plutonium-239 with an isotopic purity of at least 94%. According to current estimates, in the five countries that have nuclear weapons, building a nuclear device requires 8kg of plutonium or 25kg of highly-enriched uranium (HEU); although some specialists suggest 4kg to 5kg of plutonium or 16kg of HEU would be sufficient. With 20% enriched uranium, it would take 800kg of material to reach the critical mass needed for a nuclear explosion, which is believed to be technically implausible [3].

Obtaining fissile weapons grade materials is no easy matter for terrorists, chiefly for the following reasons.

Enriching uranium or producing the necessary quantity of plutonium requires scientific and technological facilities that no terrorist organisation has.

Acquiring the necessary quantities of fissile weapons-grade materials on the black market would require the relevant supply, which is not currently there (the IAEA receives about 150-200 reports from Member States each year of fissile materials that are lost, stolen or otherwise out of their control, but, first, most incidents are unrelated to weapons-grade uranium or plutonium and, secondly, in all reported incidents the fissile materials are returned under proper control).

Should terrorists nevertheless succeed in obtaining the requisite quantity of weapons-grade uranium or plutonium, as a study commissioned in 1977 by US Congress showed, a small group of people who had never had any access to classified information could develop and build a primitive nuclear explosive device [4]. To do so, according to estimates at that time, they would need up to US$ 1 million, a medium-size workshop, at least one specialist who is conversant with the relevant literature, and an engineer.

Today, some solutions are within an easier reach for terrorists compared to the 1970s, largely thanks to information technologies. However, any active application of such technologies leads to higher risk of detection. Queries regarding nuclear weapons development made using internet browsers can be traced by intelligence services [5].

Importantly, nuclear devices built under such conditions can hardly be expected to be reliable, since given the lack of specialists, high-precision equipment, and testing capabilities, it would be difficult to avoid errors during the development or assembly of any such device. In addition, handling major amounts of cash or sourcing fissile weapons-grade materials in the required quantities would inevitably put the terrorist cell on the radars of the intelligence services of a number of countries. As a result, having risked substantial amounts of money and possible detection, an organisation planning to commit an act of nuclear terrorism would have to accept that the outcome is uncertain, at best.

Terrorist’s Red Button

A terrorist organisation runs a higher chance of succeeding in creating a nuclear device if it is helped by a state with an existing nuclear programme. According to Graham Allison, Director of the US Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs, in the event that a nuclear weapon were to used by terrorists anywhere in the US, the prime suspects would be Russia, Pakistan and North Korea, as well as Ukraine and Ghana.

Graham Allison identifies these countries not because they have difficult relations with the US, but rather because he believes that these countries offer a range of opportunities for terrorists to acquire nuclear weapons, materials, or technologies. Russia has the largest nuclear arsenals and a major stockpile of fissile weapons-grade materials. Pakistan is known for its links with terrorist cells. North Korea is party to missile and nuclear proliferation. And both Ukraine and Ghana host research nuclear reactors involving HEU that terrorists could target in order to build their own nuclear device [6].

In fact, no state can guarantee that it has fully excluded any possibility of it losing control over its nuclear weapons or components of its nuclear programme, that nuclear programme employees might establish links with terrorist cells, that terrorists might penetrate nuclear facilities, or the other risks which, if they were to materialise, would enhance the probability of nuclear terrorism. The examples below serve to illustrate these risks in the US and other countries.

In January 1961, a B-52 strategic bomber crashed in North Carolina; it was carrying two hydrogen bombs, one of which broke up as a result while the other one nearly exploded – with three out of four triggers activated.

Any country with a nuclear programme faces the risk of losing control over it; there is therefore an assumed probability that terrorists could be in a position to acquire nuclear armaments. Russian experts believe it highly unlikely that terrorists could gain unauthorised access to nuclear devices either deployed on the ground or placed in centralised storage facilities, and argue it is more likely that they would be stolen during transportation

In August 2007, another B-52 was flying from an airbase in North Dakota to an airbase in Louisiana carrying twelve cruise missiles, six of which were equipped, erroneously, with nuclear warheads, a fact which was discovered only after the bomber had landed.

In July 2012 the Y-12 nuclear facility in Tennessee, which stockpiled HEU, among other materials, was broken into illegally by three pacifists, including an 82 year old.

The above incidents show that any country with a nuclear programme faces the risk of losing control over it; there is therefore an assumed probability that terrorists could be in a position to acquire nuclear armaments. Russian experts believe it highly unlikely that terrorists could gain unauthorised access to nuclear devices either deployed on the ground or placed in centralised storage facilities, and argue it is more likely that they would be stolen during transportation [7].

Should this risk materialise in a nuclear state, the terrorists would hardly be able to use the nuclear weapon. To do so, they would need to apply certain required procedures related to storage conditions. For example, if they were to acquire a nuclear device from Russia or the US, in order to activate the device they would need to break the inbuilt security codes that bar the unauthorised use of nuclear weapons [8].

In countries with less sophisticated security regarding nuclear weapons than Russia or the US, the terrorists still face other barriers. For instance, if they were lucky enough to penetrate a military nuclear programme facility anywhere in Pakistan, they would gain access not to ready-made weapons but to isolated components. Feroz Khan, a former director of arms control and disarmament affairs in the Strategic Plans Division of the Joint Services Headquarters of Pakistan, argues that, in his country, nuclear warheads are kept separate from their delivery vehicles [9]. And that munitions are not equipped with nuclear charges in peacetime. There is the same practice in India.

While the threat of nuclear attack by a terrorist cannot be fully excluded, a review of the situation seems to suggest that the probability of any such threat materialising remains extremely low. This is not to say that the probability of nuclear terrorism is low, since the 2005 Convention extends the definition to the threat of using nuclear weapons. Incidents like this have happened in several countries, including Russia, the US, and France.

Of particular relevance were the events of 1974, when the FBI received a letter demanding US$ 200,000 in cash is left in a specified location under a threat to activate a nuclear device in Boston. Although this demand proved to be nothing but an attempt at extortion, having realised they were poorly prepared for such scenarios, the US authorities established a specialised task force under the Department of Energy called a Nuclear Emergency Search Group [10].

“Dirty Bomb”

Based on the opinion presented by the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (the Evans-Kawaguchi Commission), the chances of terrorists detonating a nuclear explosion are less than that of causing radioactive contamination [11]. In other words, acts of radiological terrorisms are more likely than acts of nuclear terrorism.

Radiological terrorism leads to the radioactive contamination of facilities and locations. According to Arutyunyan and Bilashenko (Institute of Secure Atomic Energy at the Russian Academy of Sciences), “even in situations in which low-activity radioactive substances are dispersed, radioactive contamination can still be registered over long distances, affecting massive numbers of people who find themselves in an environment that they perceive as dangerous for their own health and for the health of their loved ones.” [12]

Importantly, it is not only that such an environment is hazardous to human life or health. First, it causes considerable damage and dealing with the consequences may require a great deal of time and resources; and secondly, it spreads panic.

Acts of radiological terrorism come in two categories:

- dispersing radioactive substances over infrastructure facilities; •

- attacking nuclear facilities, which may lead to radioactive contamination over extensive areas.

In the first instance, terrorists could target administrative, business, or information hubs, transport communications, food storage, or water systems [13]. In terms of danger to life, human beings are most threatened by radionuclide sources such as Iridium-192, Cobalt-60, Promethium-147, Strontium-90, Caesium-137 and Cerium-144. In terms of contamination, it is Americium-241, Iridium-192, Californium-252, Cobalt-60, Promethium-147, Ruthenium-106, Strontium-90, Thulium-170, Caesium-137 and Cerium-144 that are most dangerous [14].

Under the second scenario, the targets would include atomic power stations and other facilities under civilian or military nuclear programmes. Russian experts maintain that an aircraft ram attack against one of the spent nuclear fuel storage facilities at Andreeva Bay could lead to radioactive contamination of Murmansk [15].

How to make acts of nuclear terrorism less likely

While the threat of nuclear attack by a terrorist cannot be fully excluded, a review of the situation seems to suggest that the probability of any such threat materialising remains extremely low.

Russia can boast substantial expertise in nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation. In the troubled 1990s, the country destroyed tens of thousands of nuclear warheads and dismantled and converted hundreds of nuclear delivery vehicles. Russia has spared no effort to enhance the physical protection, control over and accounting for nuclear munitions and materials. Russia also has a sad legacy of terrorism in the country, which has seen thousands of lives lost through acts of terror. Combining expertise in nuclear disarmament with lessons learned in fighting terror should present sustainable approaches to preventing nuclear terrorism.

As a result of the growing challenge of terrorism in the 21st century, there has been greater focus on the threat of the acquisition of nuclear materials or even nuclear munitions by terrorists. Various steps have been taken to counter nuclear terrorism at the national, multilateral, and global levels. Russia has played an active and, at times, a leading role in numerous initiatives, including the Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism (2005); Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (2003); Proliferation Security Initiative (2006), UN Security Council Resolutions 1540 and 1887 (2004 and 2009 respectively), and other programmes.

However, despite the existing international cooperation in countering nuclear terrorism, there remain significant differences in the leading countries’ positions. To ensure that counter-terrorism works, countries should strive to overcome these differences, so that they are better able to rely on international efforts in this area. Failing that, cooperation between intelligence services, information sharing, improved laws, and other measures remain important but will obviously be insufficient without this broader framework.

1. Fochkin O. Aum Tapping Brains? // Moskovsky komsomolets. – 22 February 2005 (in Russian)

(http://www.mk.ru/editions/daily/article/2005/02/22/199531-aum-vzyalsya-za-um.html)2. Tsvetkova B. Refuting Myths: why we should not be scared by the nuclear terrorism threat from Russia // Indeks bezopasnosti. – 2011. – No 3 (94). – T. 16. – P. 50 (in Russian)

3. Nuclear Technologies. Challenge of Terrorism. Nuclear Non-Proliferation. / V.I. Boiko et al. – Tomsk: Tomsk Polytechnic University, – 2008. – P. 107 (in Russian)

4. Nuclear Proliferation and Safeguards. – Washington: Office of Technology Assessment, 1977. – P. 140.

5. For more detail on web-sites and keywords monitored by the US Department of Homeland Security, see Publicly Available Social Media Monitoring and Situational Awareness Initiative: Privacy Impact Assessment for the Office of Operations Coordination and Planning. – Washington: Department of Homeland Security, 2010.

6. Graham Allison. How to Stop Nuclear Terror // Foreign Affairs. – 2004. – Jan.-Feb. – P. 67.

7. Nuclear Proliferation / Ed. V.A. Orlov. – Moscow: PIR-Centre for Political Studies, 2002. – T. I. – P. 398; Khodorenok M.M. Nuclear Weapons under Seven Locks // Voyenno-promyshlenny kurier. – 11 August 2004 (in Russian)

8. Pikayev А.А., Stepanova Ye.A. Non-proliferation and nuclear terrorism // Nuclear Arms after Cold War / Ed. A.G. Arbatov, V.Z. Dvorkina. – Moscow: Russian Political Encyclopedia, 2006. – P. 339 (in Russian)

9. Khan F.H. Eating Grass: the Making of the Pakistani Bomb. – Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012. – P. 293.

10. Kaplan F. Mobile Teams on Hunt for Atomic Threats // The Boston Globe. – Sept. 6, 2002.

11. Eliminating Nuclear Threats: A Practical Agenda for Global Policymakers. – Canberra: International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and disarmament, 2009. – P. 39.

12. Arutyunyan R.V., Bilashenko V.P. Radiation terrorism in the context of non-proliferation // Strengthening Russian-US cooperation on nuclear non-proliferation. – Washington: The National Academies Press, 2005. – P. 216.

13. Nuclear Technologies. Challenges of Terrorism. Nuclear Non-Proliferation. / V.I. Boiko et al. – Tomsk: Tomsk Polytechnic University – 2008. – P. 332. (in Russian)

14. Ibid. – P. 351.

15. Arutyunyan R.V., Bilashenko V.P. Radiation terrorism in the context of non-proliferation // Strengthening Russian-US cooperation on nuclear non-proliferation. – Washington: The National Academies Press, 2005. – P. 217.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |