Mongolia: Bright Prospects for Dynamic Growth

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Head of the Mongolia Unit, Senior Researcher at the Korea and Mongolia Division, Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences

Having remained, for decades, on the back burner of international affairs, Mongolia has lately been attracting attention and interest on the part of the international community, policy-makers, political scientists, economists, businessmen and the mass media. The Russian media carried a number of stories with controversial assessments of processes currently under way in the neighbouring friendly country.

Having remained, for decades, on the back burner of international affairs, Mongolia has lately been attracting attention and interest on the part of the international community, policy-makers, political scientists, economists, businessmen and the mass media. The Russian media carried a number of stories with controversial assessments of processes currently under way in the neighbouring friendly country. (1, 2, 3)

The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Frontier Securities” and other multilaterals list Mongolia among countries expected to begin periods of fast growth in the near future. According to estimates by the Economist Intelligence Unit in late 2012, the Mongolian economy will grow at a rate of 13 per cent a year on average over the next several years (the first in the list was Macao at a rate of 14 per cent). The Financial Times has introduced a new term - M-3 countries - to denote the three countries with substantial endowments of natural resources and the highest rate of economic growth worldwide: Mongolia, Mozambique and Myanmar.

According to World Bank estimates, Mongolia's economy in the coming decade will grow on average at 15 per cent, and Mozambique and Myanmar at 10–12 per cent. In 2011, Mongolia's GDP increased by 17.3 per cent, and in 2012, by a further 12.3 per cent [1]. In 2013, with the worsening of global economic conditions, reduced foreign investments and dwindling exports of Mongolian coal to China, and due to other recent constraints on the implementation of the investment contract by Rio Tinto at the major Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold deposits, the rate of economic growth in Mongolia fell, but not significantly.

Reasons for Increased Interest in Mongolia

The heightened interest in Mongolia has been generated by a number of geopolitical, strategic, economic and other factors.

The Financial Times has introduced a new term - M-3 countries - to denote the three countries with substantial endowments of natural resources and the highest rate of economic growth worldwide: Mongolia, Mozambique and Myanmar.

Mongolia is evolving into an arena for open or hidden political and economic confrontation involving some of the world's leading economies, including Russia, China, the US, Japan, the EU, the UK, Canada, and South Korea.

Mongolia occupies an important strategic position at the heart of Inner Asia, between two great powers, Russia and China.

Before the 1990s and for almost seventy years, Mongolia was drawn into the orbit of the powerful and domineering political and economic influence of the USSR. Following the peaceful democratic revolution in Mongolia in 1990, the disintegration of the USSR in 1991, and the massive reduction in economic assistance by Russia and Russian-Mongolian political, commercial and economic as well as cultural and other links, the Mongolian economy was on the brink of collapse. The country had to look for ways on its own to survive the very difficult period of transition.

At the same time, even during the hardest times of the 1990s, the joint Russian-Mongolian majors ("the three pillars") - Erdenet mining factory, Mongolrostsvetmet, and Ulan-Bator Railways - that had been largely responsible for much of the government's revenues, overcame severe hardships during the shock of the accelerated transition to a market economy, hence saving themselves and Mongolia from economic downfall.

Relying on assistance from advanced economies (the US, Japan, the UK, South Korea, etc.) and international institutions (the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, Asian Bank of Development, and the UNDP), Mongolia sailed fairly rapidly through the most difficult crisis of the transition and embarked on an independent, open, and multi-pillared foreign policy. In the 1990s, political, economic, cultural and humanitarian positions that Russia had in Mongolia were significantly weakened while those enjoyed by the USA, China, Japan, the UK, Canada, Germany, South Korea and some other advanced economies consolidated considerably.

Today's Mongolia is one the more convincing examples of a relatively rapid and successful transformation of a formerly communist country into a modern, dynamic and democratic country with a multi-party political system, market economy and transparent foreign policy. In one of her interviews in Mongolia in 2012, Dr. Frances T. Pilch, Professor of Political Science at the United States Air Force Academy, said that Mongolia had become a laboratory for democracy. Leaders from the US, UK, Germany, France, Japan, South Korea and other countries believe that Mongolia is setting an example for the promotion of western style democracy, as was further confirmed by Mongolia assuming the Chairmanship of the Community of Democracies for 2011–2013. (1, 2, 3)

Even during the hardest times of the 1990s, the joint Russian-Mongolian majors Erdenet mining factory, Mongolrostsvetmet, and Ulan-Bator Railways overcame severe hardships during the shock of the accelerated transition to a market economy, hence saving themselves and Mongolia from economic downfall.

Another important factor, driving interest from policy-makers and business communities from the developed and emerging markets towards Mongolia, lies in its rich natural resources, including coal, copper, molybdenum, gold, silver, uranium, and rare earth elements. According to some Western observers, the top 10 Mongolian deposits of coal, copper gold, uranium and rare earths alone are worth USD 2.75 trillion. Significantly, only one third of Mongolian territory has so far been exposed to prospecting and exploration.

Fighting for Mongolia’s Mineral Riches: Results So Far

With global natural resources increasingly depleted and shrinking, and with the ever expanding demand for mineral resources worldwide, many countries and major multinational corporations view Mongolia's rich but not fully exploited mineral resources as a large and coveted piece of the dwindling global mineral resources pie” (e.g., UK-Australian Rio Tinto; Chinese Shenhua and Chalco; US Peabody Energy; Japanese Itochy, Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumimoto, and Marubeni).

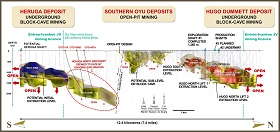

Foreign companies are particularly interested at the moment in such Mongolian deposits as Oyu Tolgoi (copper and gold); Tavan Tolgoi (thermal and coking coal); Dornod (uranium); and others. As the latest research has shown, the Tavan Tolgo coalfield, not yet fully expolited, might have up to 7.4 bln. tons of coal, of which 1.4 bln. tons is coking coal, and 4.6 bln. tons coal for use in power stations. Rio Tinto believes that the large Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold deposit in South Gobi, some 80 km from the Chinese border, has 25 mln. tons of copper worth some 50 years of exploration. (1, 2)

At the end of 2012, Rio Tinto, which owns 66 per cent of the joint venture, Turquoise Hill Resources (or Эрдэнэс Оюутолгой in Mongolian), completed the construction of a mining and concentrating factory at the copper field; by mid-2013, the company had produced and exported to China their first shipment of 576 tons of copper concentrate, marking the completion of the first stage. Today, the joint company is holding negotiations at board level to find ways out of a delicate situation in which the company has found itself following the decision of the newly elected government in Mongolia to revise some of the clauses of its 2009 investment agreement.

Today's Mongolia is one the more convincing examples of a relatively rapid and successful transformation of a formerly communist country into a modern, dynamic and democratic country with a multi-party political system, market economy and transparent foreign policy.

A new concentrating factory at Oyu Tolgoi will be 1.5–2 times as big as the Russian-Mongol Erdenet, which, in turn, is one of the top 10 such factories worldwide. By the end of 2013, in the first 6 months after commissioning, the company had produced over 250,000 tons of copper concentrate, with plans to steadily increase production to 692,000 tons in 2014. By comparison, Erdenet in 2013 produced 530,000 tons of copper concentrate. The second stage of the Oyu Tolgoi Project will also have an ore mine built. With this, Mongolia will become a major player in the world copper market.

Mongolia’s Foreign Policy and Russian-Mongolian Relations

Russia, traditionally, has had and continues to have vital strategic interests in Mongolia: political, economic, military and strategic, environment, historic, cultural and humanitarian. For ages Russia and Mongolia have been linked together by multiple factors: they share 3.5 thousand km of joint borders; an age-long history of predominantly friendly relations; the unique, allied tenure of Soviet-Mongolian relations in the 20th century; the important contribution that Russia made towards the revival and defense of the statehood and independence of Mongolia and development of its economy and culture; the shared pattern of political, social and economic change in the two countries after 1990; in many respects common strategic national interests; a strategic partnership and shared interests in promoting security and peace in Asia Pacific, in regional and global economic integration, and in making Mongolia a modern, independent and prosperous country.

The 2011 updated version of the Mongolian Foreign Policy Conceptual Framework plans to pursue independent, autonomous, ‘multi-pillared’ foreign policy aimed at maintaining balanced relations both with Russia and China, and with other developed and influential Western and Eastern countries. Central to Mongolia’s foreign policy is the “third neighbour” concept extended to the US, Japan, EU, India, South Korea and Turkey. At the same time, Mongolia is keen to avoid ending up extremely and unilaterally dependent on any of the great powers. The current Mongolian leadership is oriented mostly towards Western values of democracy and the market economy. In recent years, a special emphasis has been placed on promoting comprehensive and, importantly, commercial and economic links with the EU and the introduction of European rules and standards.

After 2009, Russian-Mongolian relations have been, in many respects, purely declarative. With all its outward benevolence, many earlier agreements and arrangements have never been put in practice, inter alia, due to Mongolia. There has been a lack of progress in the implementation of the two new major joint projects signed at the intergovernmental level back in 2009. These concerned plans to set up a joint infrastructure company (together with Russian Railways) to upgrade the Ulan-Bator railway and construct new railroads to ship coal from Tavan Tolgoi along the Tavan Tolgoi – Sainshad –Choibalsan – Solovievsk route towards the Trans-Siberian railway and further up to Japan or South Korea.

With global natural resources increasingly depleted and shrinking, and with the ever expanding demand for mineral resources worldwide, many countries and major multinational corporations view Mongolia's rich but not fully exploited mineral resources as a large and coveted piece of the dwindling global mineral resources pie.

In May 2013, the Mongolian government decided to sell its 50 per cent interest in the infrastructure project with Russian Railways. Currently, 100 per cent of the company’s shares are owned by Russian Railways, although it has been agreed upon that over the next several years, Russian Railways will focus on the modernisation of the Ulan-Bator railway.

In December 2013, a first meeting was held in Ulan-Bator between the railway authorities of Russia, China and Mongolia to discuss pressing issues over cooperation in transit traffic, more specifically, along the Northern Corridor of the three countries’ railway transportation routes.

In 2009, the countries signed an intergovernmental agreement to establish a joint Russian-Mongolian company, Dornod Uranium, to prospect for, produce, process and use uranium from Eastern Mongolia’s uranium deposits. In 2010, an agreement was signed specifying the terms and conditions for the creation of Dornod Uranium, arranging that the articles of association would have been signed in the immediate future subject to the agreed upon principles. However, the project has seen no progress whatsoever.

These lengthy delays had to do with the fact that in May 2011, Khan Resources, a Canadian company, sued the Mongolian government for the alleged illegal revocation of its license to explore uranium ores at Dornod, and the action has been pending, for some years, at the international arbitration tribunal.

Russia has lost its place to competition with regards to potential plans for participating in the development of a major coalfield at Tavan Tolgoi by building some 1,800 km of new railroads. Until recently, trade and economic relations had been progressing, but not nearly fast enough, particularly compared to more dynamic relations between Mongolia and a few other leading economies, in particular China.

After 2009, Russian-Mongolian relations have been, in many respects, purely declarative. With all its outward benevolence, many earlier agreements and arrangements have never been put in practice.

In 2010–2013, Russia accounted for an average of 15–18 per cent of Mongolia’s foreign trade, against China’s nearly 50 per cent [2]. In 2012, Russia’s share of Mongolian imports amounted to 27.4 per cent, and barely 1.8 per cent of exports, against China’s 92.6 per cent of Mongolian exports and 27.6 per cent of imports [3]. Additionally, for a number of years now China has been quite far ahead of other foreign investors in the Mongolian economy. According to Mongolian sources, in 1990–2010, direct investment by China in Mongolia totaled nearly USD 1.8 bln., or nearly 53 per cent of all direct foreign investment (FDI) in the country. Over the last two decades, Mongolia has established over 5,300 firms with Chinese equity, or almost 50 per cent of all foreign-equity companies [4]. Over the same period, 769 firms with Russian capital were set up, and Russia has contributed less than 2 per cent of direct foreign investments in the Mongolian economy [4].

There are still important obstacles in bilateral relations, including the visa regime; high customs duties on traditional Mongolian goods exported to Russia; high transportation charges applied to Mongolian goods in transit across Russia; and cumbersome bureaucratic procedures to obtain approvals and permits and in customs clearance. Many Mongolian businessmen today prefer Chinese, Japanese or Western companies to dealing with Russian businesses.

There are still important obstacles in bilateral relations, including the visa regime; high customs duties on traditional Mongolian goods exported to Russia; high transportation charges applied to Mongolian goods in transit across Russia; and cumbersome bureaucratic procedures to obtain approvals and permits and in customs clearance.

Any further consolidation and strengthening of Russia’s strategic positions in Mongolia will have to take into account the following.

1. Given the growing competition on the part of the old and emerging powers and multinational corporations with their own national interests in Mongolia (China, the US, Japan, South Korea, EU countries, the UK, Germany and so on), and to prevent any additional weakening of the Russian positions and growing negative imbalances between Russia, Mongolia, China and the US (the list to be augmented with Japan soon), Russia must consistently pursue a policy of a comprehensive revitalization and greater effectiveness of bilateral relations in all areas listed in the 2009 Joint Declaration on the promotion of a strategic partnership between Russia and Mongolia based on the principles of equality and mutual benefit; towards consolidation and strengthening of earlier progress and gaining new positions in all areas of public life in Mongolia (politics, economy, defense, education, science, culture, promotion of the Russian language, etc.); towards a more thorough understanding of national interests and proposals from Mongolian partners, and further strengthening and development of the bilateral strategic partnership.

2. Russia should ensure that Mongolia expedites its decision to eliminate visas. Proposals by the Russian Ministry for Foreign Affairs are currently pending consideration by Mongolia.

3. Additional steps should be taken to expand bilateral trade and reduce growing trade imbalances.

4. Heeding to positive as well as negative lessons from the history of Russian/Soviet – Mongolian relations in the 20th century, an emphasis should be placed on creating and retaining the traditionally friendly and positive image of Russia among new generations of Mongolians. We should consistently and actively counter any attempts by Mongolian politicians or historians, who allege the need to restore historical justice and try to impose an imbalanced, mostly negative interpretation of the complex and controversial history of Soviet-Mongolian relations and the role of Russia/USSR in the history of Mongolia in the 20th century.

5. The elaboration and implementation of long- and mid-term programmes and projects of social, economic and cultural development in East Siberia, Buryatia, Baikal and other regions in the Russian Federation that border on Mongolia should fully consider interests and opportunities for cooperation with Mongolia.

6. Mongolia’s unlimited potential as a transit country should be tapped more broadly to promote commercial, economic, energy, logistical, tourist and other cooperation ties with China and other countries in Asia Pacific, and develop mutually beneficial trilateral cooperation and partnership between Russia, Mongolia and China.

1. Mongolia Today (in Russian), 11.03.2012.

1. Монгол улсын статистикийн эмхтгэл. Mongolian Statistical Yearbook. 2012. Улаанбаатар, 2013

2. Монгол улсын статистикийн эмхтгэл. Mongolian Statistical Yearbook. 2010; 2011; 2012. Улаанбаатар (in Mongolian).

3. Монгол улсын статистикийн эмхтгэл. Mongolian Statistical Yearbook. 2012. Улаанбаатар, 2013. P. 269–271.

4. Baatar Ts. Foreign direct investment in the case of Mongolia // Олон улсын монголч эрдэмтдийн Х их хурлын илтгэлууд. Proceedings of the 10th international Congress of mongolists. Vol. III. Mongolia’s economy and politics. Улаанбаатар, 2012. P. 145–148.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |