There is a certain paradox in the state of Russian-Mexican affairs today. On the one hand, we see a high level of political dialog, showing aligned or close positions on most of the current global policy issues, but on the other, the scope of trade and economic ties is extremely narrow compared to other leading Latin American countries. This was duly pointed out by the Mexican Ambassador to Russia, Ruben Beltrán, who presented his credentials to President Vladimir Putin in January 2013. What, then, are the reasons for this imbalance in relations between the two countries?

New Relations in the Making

In June 2004, during an official visit to Mexico by Russian President Vladimir Putin, a number of documents signed by the two countries registered their aligned or close positions on a broad range of world policy issues. The joint communique noted in particular the common interests of the two countries in strengthening the multipolar system of international relations, recognizing the role of the United Nations as the central mechanism for their regulation and stressing the need to build up efforts in combating terrorism, drug trafficking and transnational crime [1]. The countries made a special note of the significant gap between political contacts and economic collaboration, suggesting ways to enhance bilateral ties. It was, significantly, the first visit by a Russian leader in the 120-year long history of relations between the two countries, and not just to Mexico but to the Latin American continent in general.

Russian-Mexican relations did not in fact evolve as smoothly as could be inferred from the signed declarations. There were a number of reasons why Mexico initially had a rather negative picture of the “new” Russia.

One of the reasons was the not altogether coherent policy of the Russian leadership, which was reducing its presence in the region in a rather disorganized way. This manifested itself quite graphically in Russia’s withdrawal from Cuba, which looked more like desertion.

Secondly, Russia’s 1993 International Policy Doctrine listed Latin America last in the list of regions (after Africa), as had been customary back in Soviet times.

Thirdly, there were a number of incidents, all related to Mexico, that rarely happen in diplomatic life. In 1995 alone, a visit by the then Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev to Mexico was announced five times, each time only to be scrapped at the last minute without any reasonable explanation. It is not difficult to imagine Mexico’s reaction.

As a result, Mexico’s negative perception of the “new” Russia was, to a large extent, Russia's own doing, and something had to be done urgently to improve its unfortunate image. Appointed as Foreign Minister in January 1996, Yevgeny Primakov took his first extended foreign trip to Latin America as early as May, and started with Mexico [2]. His visit helped to resume political dialog, and more than 10 documents on cooperation in various areas were signed. Two combined intergovernmental commissions were set up: one on economic, trade, science and research cooperation and sea navigation, and the other on cultural cooperation. In addition, an arrangement for political consultations between the two foreign ministries was put in place.

No Real Advance

While the 2004 visit by Vladimir Putin to Mexico was instrumental in broadening the scope of the dialog, it failed to address bottlenecks in cooperation, in particular in trade and economy. This was due, largely, to the fact that the high-profile projects announced had never materialized, such as the one proposed by Russia to supply LNG from its Far East to Mexico’s Pacific coast; no practical steps towards this goal were made, effectively discrediting the very idea. Also of certain consequence were the largely obsolete legal instruments dating back to the 1970-80s, and those could not be properly updated until Russia joined the WTO (in 2013).

During the 2004 Russian presidential visit, and the return visit to Moscow by Mexican President Vicente Fox in June 2005, Mexico confirmed its support of Russia’s accession to the WTO. However, bilateral trade between the two countries remained tiny, amounting to a few hundred million dollars. In 2002–2003, Mexico accounted for a meager 0.1 per cent of Russia’s foreign trade total [3]. In addition, Mexico often subjected Russian exporters to antidumping measures, alleging that Russia was not a market economy.

By the second decade of the 21st century, the two countries have basically stopped student and professor exchanges, ceasing any cooperation in the scientific and academic spheres.

Some Progress

Nevertheless, the scope of collaboration has been expanding in both the political and economic spheres, albeit rather slowly, as shown by the June 2011 visit to Russia by Mexico’s Foreign Minister Patricia Espinosa. During her visit, the countries signed a Program of Scientific and Technical Cooperation for 2011–2013, listing 18 joint projects in airspace, nanotechnology, health care, biotechnology and other areas. Talking to her Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov, Ms. Espinosa announced the decision by the Mexican Government to recognize Russia as a market economy.

By 2013, trade between Russia and Mexico reached a record-breaking amount of almost USD 1.6 bn. [4], having grown 200 per cent in the period between 2008 and 2012. This allowed Mexico to move to fourth place among Russia's Latin American partners (after Brazil, Argentina and Ecuador) [4]. However, the two countries continue to believe that there is much more untapped potential in trade and economic cooperation.

One of the most neglected areas in cooperation has been tourism. While more than 80,000 Russians visited Mexico in 2012, Mexicans think their numbers could realistically be much higher. According to Mexican Ambassador Ruben Beltrán, the Mexican leadership aims to make sure that the number of Russian tourists grows to 500,000 by 2018.

Admittedly, the war on drug cartels that Mexico has been waging since 2006 has led to more than 55,000 casualties, including quite a few foreigners, and affected the famous Mexican resorts, which has not been helpful to plans to make Mexico a tourist Mecca.

Mexico and the Recent Financial Crisis

By the end of the first decade of the 21st century, Mexican leadership came to the realization that their country was sinking ever deeper in the North American economic vortex as a result of NAFTA (by 2012 almost 80 per cent of Mexico’s foreign trade was with the US [5]). This was contrary to national interests and became particularly obvious during the 2008-2009 US financial crisis that triggered the global recession. Mexico, more closely twinned with the US economy than any other country, was distinctly affected by it: in 2009, Mexico’s GDP plunged by 6.2 per cent [6].

In this situation the Mexican leadership had to look for new economic partners.

Any attempts to expand its links with the leading Latin American countries and join the integration process in the region had a limited and largely symbolic effect [7].

Another area to look for potential partners was the Pacific. In 2012, Mexico initiated a Pacific alliance with Columbia, Chile and Peru.

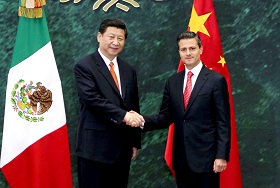

In April 2013 the newly elected president of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto, made a trip to China and Japan. Talking to the Chinese leaders, he proposed a plan of enhanced trade and economic relations with China. Importantly, the relations between these two countries in trade and economics were far from being at their best due to a large trade imbalance favoring China. One key reason was that Mexican business circles started out wary of the possibility of China dislodging Mexico from its niche in the US market.

In January 2013, Enrique Peña Nieto announced his plans to broaden trade and economic collaboration with Russia [8]. Since Mexico is one of the most open economies in the world, with free trade agreements with 44 countries, Russia now has a chance to finally start exploring the Mexican market.

Areas of Russian-Mexican Cooperation

Mexico is seeking leading positions in the global economy, and the country has no other way to do it but to intensify investment in research and technology. While Mexico is one of the biggest OECD exporters of IT equipment, it stands low in the countries’ ratings of the level of science and innovation. This opens up good opportunities for a breakthrough in the cooperation between Russia and Mexico in science and technology, given that Russia is still strong in new technologies while Mexico desperately needs them. There are good prospects for cooperation in space, nanotechnology, advanced mathematics, etc.

One of the largely underexplored areas of collaboration is in the energy sector. The two countries are among the world’s largest producers and exporters of hydrocarbons. In just a few years, the impending “oil shale revolution” in the US may dramatically change the world market for these strategic goods. Preparations for this need to begin now, and having the two countries agree on actions they will take in that sphere would be quite helpful.

Mexico offers large prospects for Russian investors, particularly as a launch point on the way to the world’s largest market in North America.

Now that Russia has acceded to the WTO it might be appropriate, having first thoroughly analyzed all pros and cons, to consider a free trade agreement with Mexico.

New impetus should be given to the Russian-Mexican commission on economic, trade, research and technology cooperation and sea navigation. The commission has been meeting irregularly and often too formally. It might be appropriate to put its work on a more practical footing, for instance, by introducing trade associations. Then it will be appropriate to consider setting up a business cooperation council, to be led not by officials but by industry captains from the two countries, who so far have known very little about each other.

In conclusion, now is the best time for the Russian-Mexican partnership to make a quantum leap, and Russia should not miss its chance this time.

1. Mexico in today’s world and Russia’s international relations. Moscow: ILA, 2005. P. 44. (in Russian)

2. The image of Russia as viewed from Latin America. Moscow, 2009. P. 23. (in Russian)

3. Mexico in today’s world and Russia’s international relations. Moscow: ILA, 2005. P. 47. (in Russian)

4. Federal Customs Service in 2012. Russian Foreign Trade Statistics by the Customs: Compilation. Moscow, 2013. P. 12. (in Russian)

5. Banco de Mexico. Cuadro A56. P. 123

6. IMF. World Economic Outlook, September 2011. Washington, 2011. P. 178–184

7. Latin America. 2013. No 6. P. 73–80 (in Russian)

8. Latin America. 2013. No 6. P. 67 (in Russian)