Insidious Air Pollution. Legal Regimes for Arctic Climate Change

In

Login if you are already registered

(votes: 6, rating: 3.67) |

(6 votes) |

LLM Public International Law — International Environmental and Energy Law, NRU HSE

LLM Public International Law — International Environmental and Energy Law

The outbreak of COVID-19, despite its horrific consequences on humanity, resulted in an unexpectedly positive effect on the global environment. Due to China’s factories shut down, port restrictions, international air traffic put on hold, the air quality and state of the environment have significantly improved. Sooner or later, when the pandemic is defeated, we will be back on track, which again means excessive pollution, poor air quality, and rising climate change issues. Ironically, the latter has something in common with COVID-19 — it knows no borders, and its consequences can be observed everywhere around the globe.

Climate change has been recognised as the “defining issue of our time.” Some regions are more vulnerable to climate change than others. As “climate change is amplified in polar regions”, the Arctic suffers the most.

Why do we bother to care? Simply because “What happens in the Arctic, doesn’t stay in the Arctic.”

The major problem of Arctic air pollution lies in the innate complexity of the region and the nature of the offshore industry. Surrounded by five different states, the Arctic is hard to manage in a unified manner. Nonetheless, the international community has agreed on certain points regarding climate change management that specifically apply to the Arctic.

The 2019 Production Gap Report established the term “fossil fuel production gap”, alluding to the discrepancy between planned fossil fuel production and the level of emissions consistent with the PA’s temperature goal. It reviewed production plans in the USA, Russia, Canada and Norway and finds that governments' planned oil and gas production by 2040 exceeds the emission level to be consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goals. Following the 2018 IPCC Report, fossil fuel emissions need to decline by approximately six and two per cent per year to stay within the 1.5 and 2°C temperature goal respectively. Although governments aim to decrease their emissions, by expanding their oil and gas industry, they are signalling the opposite.

The shipping sector has been more responsible in this regard. Despite the majority of sea-going vessels still operating on fossil fuels, it is strongly believed that zero-emission vessels are likely to emerge within the next few years. Yet, the shipping industry decarbonization will require new technologies in the fuel production field, confidence in the fuel supply chain, and diverse “ land-based infrastructure for production, supply, and distribution.” Generally, the current fuels and vessels’ engines should be all reconsidered. The popular “green” LNG is now considered as not so eco-friendly fuel due to the recent findings in a “methane slip” coming from LNG engines.

Meanwhile, Arctic states possess all the legal instruments to influence the Arctic economic boom. IEL and ICCL provide a general path to meet climate change goals, whereas LOS and IMO instruments give Arctic states all the necessary legal tools for meeting these goals. The IEL, ICCL and LOS regimes are complementary. Hence, the IEL principles are equally applicable in LOS. The IEL principles and ICCL convention and protocols also apply to the oil and gas industry, and due to a lack of specific oil and gas regulations, IEL and ICCL are key to prevent a legal vacuum. For instance, of the eight Arctic states, Russia, Norway, and the USA produce oil and gas north of the Arctic Circle. In 2018, the USA expanded federal oil and gas leasing in the coastal area of the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve in a larger area of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska and offshore. In June 2019, Russia started to drill at Payakha, possibly the biggest Arctic oil reserve. In the same year, the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy granted 13 companies offshore oil production licenses in the Barents Sea. These are examples of states that exercise their right to permanent sovereignty. By exercising their right, allowing this particular use of their territory, they cause transboundary harm to one another and to the rest of the world. The gasses emitted from the burning of oil cause and amplify climate change. Should the transboundary harm principle not cap the sovereignty of the Arctic states in this regard? The transboundary harm principle and all connected IEL principles, such as the precautionary and polluter pays principles, should be triggered by emissions from the oil and gas industry, as well as from the shipping industry.

We welcome the Arctic economic boom as it means progress, development, and economic growth of the region known once as a no-man land. Yet, to keep the Arctic and Earth’s environment balanced, an immediate “greening” of two major industries is urgently needed.

The outbreak of COVID-19, despite its horrific consequences on humanity, resulted in an unexpectedly positive effect on the global environment. Due to China’s factories shut down, port restrictions, international air traffic put on hold, the air quality and state of the environment have significantly improved. Sooner or later, when the pandemic is defeated, we will be back on track, which again means excessive pollution, poor air quality, and rising climate change issues. Ironically, the latter has something in common with COVID-19 — it knows no borders, and its consequences can be observed everywhere around the globe.

Climate change has been recognised as the “defining issue of our time.” Some regions are more vulnerable to climate change than others. As “climate change is amplified in polar regions”, the Arctic suffers the most.

Why do we bother to care? Simply because “What happens in the Arctic, doesn’t stay in the Arctic.”

Cryosphere and the Ocean support the climate systems of the Earth “through a global exchange of water, energy, and carbon”. As the Arctic sea ice reflects about 80 per cent of the sunlight, it “helps to stabilise global temperatures.” However, the Arctic is changing. According to scientific reports, “annual average warming in the Arctic continues to be more than twice of the global mean; surface air temperatures in recent years exceeded those of any year since 1900, and the volume of winter sea ice has declined by 75 per cent since 1979.” One of the reasons for such climatic changes is excessive air pollution coming from offshore activities.

Producing, processing and combusting oil and gas release large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), two core greenhouse gases (GHG). The majority of anthropogenic emissions on a global scale are oil-related, and, although burning natural gas emits less CO2 than combusting oil, its primary component methane is more potent than CO2. The Arctic holds considerable oil and natural gas resources from which the majority can be found offshore. Today, it accounts for 10 per cent of the conventionally discovered and produced oil and gas and 16 per cent of the global oil reserve, 30 per cent of gas, and 38 per cent of natural gas liquids of the undiscovered but renewable.

Besides, rising marine shipping is responsible for a significant amount of GHG emissions, such as CO2, NOx and SOx, and black carbon (BC/PM). BC is the second biggest anthropogenic climate pollutant behind CO2, which impacts local air quality and the global climate. Global BC emissions by marine vessels are expected to quintuple by 2050 compared to 2004-levels based on the increasing shipping demand of which a growing share will occur in the Arctic.

The oil and gas, as well as the shipping industry, are interrelated as the former operates through oil tankers, when, for instance, it transports oil, and the latter mainly drive on fossil fuels. Consequently, the industries sustain one another and cause grave air pollution.

“The Arctic climate is shifting to a new state” and all the changes happening within the region have destructive effects on the planet in general and on the adjusting Arctic states in particular. Yet, immediate changes in air pollution levels can have immediate effects. However, climate change in the Arctic cannot be regulated by means of only one legal regime. The article will discuss the complementary role of the applicable regimes in this issue - International Environmental Law, International Climate Change Law and Law of the Sea.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Paris Agreement and International Environmental Law Principles

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the first treaty on climate change that lays down the building blocks for further climate protocols and agreements. It has 197 Parties, among which the Arctic states which are also part of the Paris Agreement (PA) to the UNFCCC. Admittedly, on November 4, 2019, the USA notified the UN Secretary-General of its withdrawal from the Agreement, which will take effect on November 4, 2020.

According to the UNFCCC’s ultimate objective, its Parties should stabilise "greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system” within a time-frame that allows ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, does not threaten food production and enables economic development in a sustainable manner. The Kyoto Protocol (KP) to the UNFCCC lists the six GHG covered by the UNFCCC in Annex A: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). The Paris Rulebook confirms that the PA covers the same gases plus nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). All Arctic states are developed countries and must, therefore, report on all seven gases.

The PA expands the UNFCCC’s ultimate objective as its goal is to reinforce the international community’s response to the climate change threat, whilst taking into account sustainable development. It specifies that the rise in global average temperature must be limited to well below 2 degrees Celsius, ideally 1,5 above pre-industrial levels. These goals would significantly reduce the impacts of climate change on our societies. The new environmental standards also require the global level of GHG emissions to reach its highest point as soon as possible and encourage climate resilience and low GHG emissions development.

To achieve these objectives, the Parties to the UNFCCC shall adhere to the five international environmental law (IEL) principles referred to in Article 3: the principles of sustainable development and intergenerational equity, common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR/RC), cooperation and the precautionary principle. The UNFCCC’s preamble additionally refers to the principle of permanent sovereignty over natural resources and the transboundary harm principle. The transboundary harm principle as described in the 1939 Trail Smelter Arbitration limits the right to permanent sovereignty by stating that no state can permit the use of its territory in a way that it significantly or substantially injures another state's territory or the persons and properties therein. The case concerned a Canadian company that emitted sulfur dioxide, which injured plants, trees, crop yields and soil in Washington State. The Tribunal decided that the fumes, a form of air pollution, emitted in Canada harmed the territory of the US, which is of violation of the transboundary harm principle. Since the GHG emissions from oil drilling and shipping in the Arctic cause transboundary harm in terms of climate change, the transboundary harm principle should be triggered in the same way.

The PA confirms the principle of CBDR/RC and sustainable development and requires the Agreement to be implemented in all fairness. By confirming the CBDR/RC principle, it indirectly hints at the polluter pays principle. Being an agreement to the UNFCCC, all other principles referred to in the Convention apply to the PA.

Hence, the UNFCCC, the PA and the IEL principles can help Arctic states to prevent air pollution. In the 2019 Australian Gloucester Resources case, the Court deemed a proposed open-cut coal mine contrary to the PA’s climate targets based on its (in)direct GHG emissions. In the 2020 Norwegian Climate Case, environmental organisations challenged awarded petroleum production licenses on the Norwegian continental shelf in the Barents Sea based on the Norwegian Constitution and European Human Rights Convention (ECHR). The principles of sustainable development and intergenerational equity inspired the disputed constitutional right to a safe environment. The Appeal Court referred to the transboundary harm principle and found that searching for new oil discoveries opposed the PA. It nonetheless dismissed the appeal based on the Norwegian Constitution and ECHR.

Danish-Russian Interfaces: the Arctic and The Baltic Sea Region

In the 2020 UK Heathrow Third Runway case, the Court of Appeal deemed the expansion plans of Heathrow Airport unlawful as the Government did not take into account the climate change policies required by the domestic planning legislation, IEL principles and the PA, which have been included into domestic law. Accordingly, the Government cannot limit the assessment of the project’s carbon impact on domestic carbon production. The Government also excluded non-CO2 emissions from aviation in its assessment, reasoning that the emissions cannot be readily quantified due to scientific uncertainty. As this reasoning fully contradicts and undermines the precautionary principle, the Court found this exclusion unlawful. Lastly, based on the principle of sustainable development, the Court deemed it unlawful that the Government only included climate impacts until 2050 as the project was expected to run afterwards, approximately until 2085.

These court cases illustrate the role of the International Climate and Environmental Law can play in preventing air pollution. Admittedly, as demonstrated by the discrepancy between the Australian and English versus the Norwegian court case, the outcome and also the level of protection depends on the court’s interpretation of the rules. The Heathrow case furthermore exemplifies this discrepancy within a national legal court system and gives hope for the Norwegian Climate Case that recently has been accepted by the Supreme Court, which will review the case.

How does the Law of the Sea regime deal with air pollution in the Arctic?

The legal foundation of the maritime Arctic management lies in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Besides UNCLOS, the Law of the Sea (LOS) regime is also complemented by LOS related legal instruments, adopted by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

When it comes to the issue of climate change, UNCLOS remains silent. However, it is argued that certain aspects envisaged in UNCLOS refer to climate change.

This rationale flows from the general obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment, as stated in Part XII UNCLOS.

This obligation is absolute and applies to all maritime zones established under the UNCLOS, as well as to all the offshore activities. States shall take “all measures consistent with this Convention that are necessary to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment from any source….”

Noteworthy, the list of marine pollution sources is non-exhaustive. Thus, any new source and type of pollution may be included as long as it meets the UNCLOS criteria. Besides, air pollution is a recognised type of pollution under the Convention.

Regarding oil drilling, UNCLOS provides a balanced regime between the exploitation of hydrocarbons and marine pollution prevention. Apart from the general obligations, states must report “significant and harmful changes to the marine environment” resulting from oil drilling. Additionally, Article 194 UNCLOS makes a clear connection to the IEL transboundary harm principle, as states are required to ensure that no pollution is arising from activities under their jurisdiction or beyond the areas of their sovereign rights are being enjoyed.

Moreover, Arctic states can recourse to Article 234, which regulates maritime activities in ice-covered areas within EEZ. By virtue of this Article, Arctic states can impose more stringent non-discriminatory rules and regulations on air pollution in the Arctic justifying it by “severe climatic conditions and the presence of ice.”

However, when it comes to shipping, the system is rather complex. The major source of air pollution is the vessels’ engines and the type of fuel they operate on. Therefore, the question encompasses the construction, design, equipment, and manning standards of vessels (CDEM) and the type of fuel used. Although alternative types of engines are slowly increasing, the majority of sea-going vessels are equipped with oil-diesel burning engines.

Regarding fuel types, they can be divided into two main groups — distillate fuels and residual fuels. This classification is based on kinematic viscosity and density of fuels. Distillate fuels result from crude oil refining, so they require basic filtration. Marine gas oil and diesel oil are distillate fuels that are mostly used in high and medium-speed engines.

Residual fuels need greater filtration and must be heated because of their high viscosity. These fuels are used in low/medium speed two stroke or four stroke engines. They have more energy by volume, yet, they are of low quality and “retain more pollutants from crude oil.” To date, marine heavy fuel oil (HFO/MFO) is the most conventional type of fuel used by vessels operating in the Arctic. This fuel is the cheapest and also the most popular among shipowners, despite being the most damaging one.

Arctic shipping is growing rapidly, thus, more vessels enter its freezing waters. If merchant’s vessels tend to switch to greener fuels, the cruise shipping industry remains less responsive. The majority of luxury vessels operate on HFO. Even though the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO) decided to ban HFO fuels, it would not make a big change unless the ban is supported by each vessel entering Arctic waters. The problem is that the membership to AECO is optional and depends solely on ship operators’ will to follow the same path.

The Russian and Canadian Approach to Extra-Regional Actors in the Arctic

Lately, IMO has decided to ban HFO from the Arctic starting from 2024. However, their decision is far from perfect. Until 2029, states can exclude “vessels within their domestic waters.” Russia exempts its vessels travelling along the NSR until 2029, meaning the prevalence of HFO for another decade. Some cruise shipping companies followed the same path, as Greenlandic Royal Arctic Line plans to use HFO until 2029 too. Moreover, within the ‘transitional’ 4-year period, more vessels operating on HFO are expected to enter the Arctic waters.

UNCLOS does not provide any technical regulations. Nevertheless, it refers to IMO Instruments as standard-setting legal tools in the shipping field, including the technical features of vessels. Noteworthy, the IMO Polar Code, as a legal instrument regulating ice navigation and ship design operating in polar waters, does not address issues related to air pollution. States must recourse to IMO MARPOL Annex VI which sets mandatory technical measures to reduce emissions resulting from fuel oil. Precisely — sulfur oxides (SOx), particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides (NOx), ozone-depleting substances, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). All Arctic states committed themselves to the IMO air pollution strategy through the ratification of Annex VI.

Arctic air pollution: Annex VI regulations implementation

In order to mitigate air pollution, Regulation 14 sets the limit of maximum sulfur content of fuel oils. To date, the limit has been reduced to 0.50 m/m as « the limits on sulfur oxides have been progressively tightened" over time. Also, Regulation 14 established emission control areas (ECA) where the limits of sulfur content are set at 0.10 m/m. Thus, while traversing through ECAs, a vessel must comply with stricter emission limits.

Noteworthy, even though IMO aims to establish the lowest possible limit, it has to contend with shipping industry interests, since such decisions may influence cargo flows and transport costs. Also, the limits of sulfur content strongly depend on the availability of compliant fuel and suitability of blended oils, which can replace fuel oil.

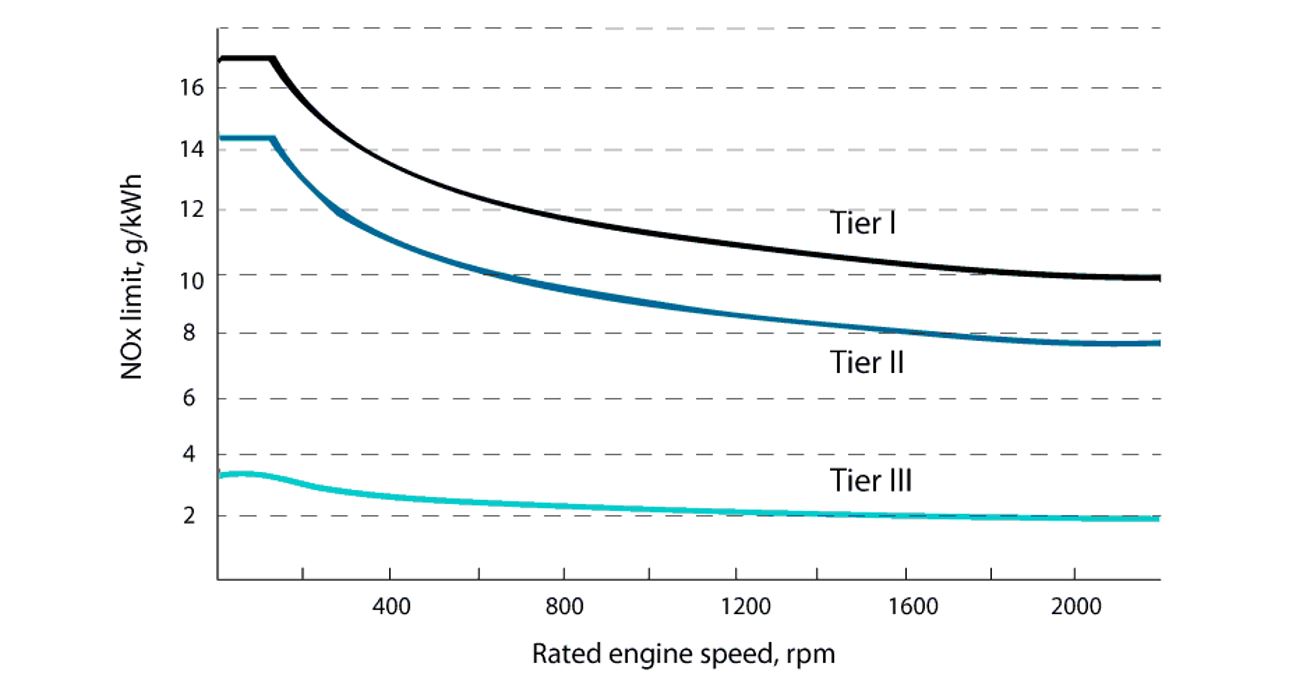

Regulation 13 covers NOx emissions via control requirements for marine diesel engines exceeding 130 kW. Such engines have to fall under one of three tiers in accordance with the date a ship was built on and its rated speed. Therefore, ships built after January 1, 2000, fall under tier I, ships built on or after January 1 2011 — tier II, and, finally, vessels constructed after January 1 2016 — tier III. The idea behind the “tier system” is that the later the date of construction, the tighter the standard for ships' engines. Through the tier system IMO pursues an idea that all new vessels will be built in accordance with the new standards and older ships will cease eventually.

Concerning VOCs, Regulation 12 prohibits the use of installations that may release ozone-depleting substances (ODS). From January 1, 2020, new ODS installations are prohibited on the board of any ship, whereas, old equipment may be still used if the “gases are dully collected” and are not deliberately emitted to the atmosphere.

https://www.airclim.org/air-pollution-ships

In 2011 and 2016 Annex VI was complemented by GHG reduction measures as a part of “global efforts to reduce atmospheric pollution”. IMO introduced special technical measures for all new ships and operational reduction measures for all ships irrespective of the year of construction which applies to vessels of 400 gross tonnage and above. Technical measures are represented by the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI), whereas, Ship Energy Efficiency Plan (SEEMP) covers operational measures. The former is a pure CDEM standards package for all new ships and the latter aims to improve the energy efficiency through operational measures like speed optimisation. Additionally, since 2019, ships over 5000 gross tonnages are required to collect fuel oil consumption data and submit it to their Flag states, which must file the data to IMO.

Yet, in order to become operative, these measures need to be dully and effectively implemented. Therefore, LOS widely relies on Port States (PS), Coastal States (CS), and Flag States (FS) powers “allocated within different maritime zones on the basis of a balance of interests.”

The Modern LOS regime retains the primacy of FS. FS is required by UNCLOS to “prevent, reduce, and control vessel-source pollution”, whereas CS and PS right to prescribe and enforce vessel-source pollution standards is limited and has optional character.

In this regard, Arctic PS can play a significant role in regulating air pollution from international vessels via Port State Control (PSC) since it compliments FS jurisdiction. The core of PSC is to make sure that vessels meet IMO requirements. To date, there are nine regional agreements - Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) on PSC. Arctic states are represented by Paris MoU and the US Coastal Guard.

PS can inspect vessels that call at their ports and further take enforcement action against them in the cases of non-compliance. PS can take enforcement action for the violation of Annex VI provisions that occurred within the limits of coastal waters and EEZ. Non-compliance can lead to, among other things, the check-up of fuel a vessel carries on board. From March 1 2020, under the sulfur cap, all vessels are obliged to have compliant-fuel on board and, in case they do not— an Exhaust Gas Cleaning System. Thus, vessels have several options to comply with the new requirements.

The statistics shown below reveal the total number of Annex VI deficienciesin 2019:

| 2019 | ODS | Quality of fuels oil | SOx | Sulphur content of fuel used | Diesel engine relating to air pollution | Fuel change over procedure | Approval of EGCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-detainiable deficiencies | 49 | 11 | 34 | 7 | 2 | 193 | 2 |

| detainable deficiencies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

By and large, PSC is a powerful tool to ensure that IMO regulations are being duly followed. For instance, recently, the US Coastal Guard detained the Motor Tanker OCEAN PRINCESS on the grounds that the vessel operated the North American ECA with sulfur content above the 0.1 per cent.

The question is whether or not Arctic PS is able to regulate fuel content beyond existing IMO standards.

So far, Arctic PS are bound by IMO standards and the burden of “greening” vessels lies on IMO.

Which law is best suited for the Arctic climate change?

The major problem of Arctic air pollution lies in the innate complexity of the region and the nature of the offshore industry. Surrounded by five different states, the Arctic is hard to manage in a unified manner. Nonetheless, the international community has agreed on certain points regarding climate change management that specifically apply to the Arctic.

Fifty Shades of Green

The 2019 Production Gap Report established the term “fossil fuel production gap”, alluding to the discrepancy between planned fossil fuel production and the level of emissions consistent with the PA’s temperature goal. It reviewed production plans in the USA, Russia, Canada and Norway and finds that governments' planned oil and gas production by 2040 exceeds the emission level to be consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goals. Following the 2018 IPCC Report, fossil fuel emissions need to decline by approximately six and two per cent per year to stay within the 1.5 and 2°C temperature goal respectively. Although governments aim to decrease their emissions, by expanding their oil and gas industry, they are signalling the opposite.

The shipping sector has been more responsible in this regard. Despite the majority of sea-going vessels still operating on fossil fuels, it is strongly believed that zero-emission vessels are likely to emerge within the next few years. Yet, the shipping industry decarbonization will require new technologies in the fuel production field, confidence in the fuel supply chain, and diverse “land-based infrastructure for production, supply, and distribution”. Generally, the current fuels and vessels’ engines should be all reconsidered. The popular “green” LNG is now considered as not so eco-friendly fuel due to the recent findings in a ‘methane slip’ coming from LNG engines.

Meanwhile, Arctic states possess all the legal instruments to influence the Arctic economic boom. IEL and ICCL provide a general path to meet climate change goals, whereas LOS and IMO instruments give Arctic states all the necessary legal tools for meeting these goals. The IEL, ICCL and LOS regimes are complementary. Hence, the IEL principles are equally applicable in LOS. The IEL principles and ICCL convention and protocols also apply to the oil and gas industry, and due to a lack of specific oil and gas regulations, IEL and ICCL are key to prevent a legal vacuum. For instance, of the eight Arctic states, Russia, Norway, and the USA produce oil and gas north of the Arctic Circle. In 2018, the USA expanded federal oil and gas leasing in the coastal area of the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve in a larger area of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska and offshore. In June 2019, Russia started to drill at Payakha, possibly the biggest Arctic oil reserve. In the same year, the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy granted 13 companies offshore oil production licenses in the Barents Sea. These are examples of states that exercise their right to permanent sovereignty. By exercising their right, allowing this particular use of their territory, they cause transboundary harm to one another and to the rest of the world. The gasses emitted from the burning of oil cause and amplify climate change. Should the transboundary harm principle not cap the sovereignty of the Arctic states in this regard? The transboundary harm principle and all connected IEL principles, such as the precautionary and polluter pays principles, should be triggered by emissions from the oil and gas industry, as well as from the shipping industry.

We welcome the Arctic economic boom as it means progress, development, and economic growth of the region known once as a no-man land. Yet, to keep the Arctic and Earth’s environment balanced, an immediate “greening” of two major industries is urgently needed.

(votes: 6, rating: 3.67) |

(6 votes) |

The Low-Carbon Agenda is Winning over the World Economy

The Russian and Canadian Approach to Extra-Regional Actors in the ArcticRussia and Canada face the need to build a balanced and cautious policy about non-Arctic states

Challenges to International Stability in 2020–2025Crisis of the state system, Economic and financial disorder, the rise of non-state actors, climate change, migrations, decline of international institutions

Danish-Russian Interfaces: the Arctic and The Baltic Sea RegionRIAC and The Danish Foreign Policy Society Report #54

Implementing Marine Management in the Arctic OceanRIAC and Polar Institute Report