Fighting Crime: Mexico’s Lessons for Russia

A Mexican soldier and a federal police officer

check vehicles for drugs

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of Political Science, Director, Head of the Center for Political Studies, RAS Institute of Latin America, RIAC Expert

Organized crime presents a grave challenge to national security in Mexico and in Russia. Both countries face the threat of growing criminality, which in the context of globalization has evolved into transnational organized crime. And although countering drug trafficking requires multilateral intergovernmental cooperation, collaboration between the two countries in law enforcement can scarcely be called effective in the light of the unsatisfactory outcome of Mexico’s wars on drugs, pervasive corruption and the growing criminal infiltration of government institutions.

Globalization in the past two decades has had a number of unforeseen implications, pointing, among other things, to the emergence of transnational organized crime (TOC) as the successor to national organized criminal gangs (OCG) both in industrially developed countries and in transition economies. TOC's global grip is now unprecedented. Criminal groups have mastered new technologies and set up networks that can only be detected through multilateral intergovernmental cooperation. Bilateral efforts cannot eradicate the criminal threat because disrupting TOC is a much more extensive challenge than fighting national criminal gangs. But while crime is becoming transnational, control over it is still limited to national borders, which seriously undermines efforts to counteract it. At the same time, international and Russian criminologists note that organized crime is getting stronger and is set to join ranks with TOC.

Russia may benefit from the lessons Mexican law enforcement agencies have learned in their efforts to counter the diverse threat posed by organized crime, as this country faces similar challenges of corruption, rising crime rate, rapid expansion of drugs among young people, a growing number of drug addicts, and the appearance of new synthetic drugs on the market. Russia's criminal environment is also influenced by factors such as the imperfect domestic criminal justice system, the judiciary, and abuses by the police and prison administration.

Evolution of Mexican Organized Crime

Bilateral efforts cannot eradicate the criminal threat because disrupting TOC is a much more extensive challenge than fighting national criminal gangs. But while crime is becoming transnational, control over it is still limited to national borders, which seriously undermines efforts to counteract it.

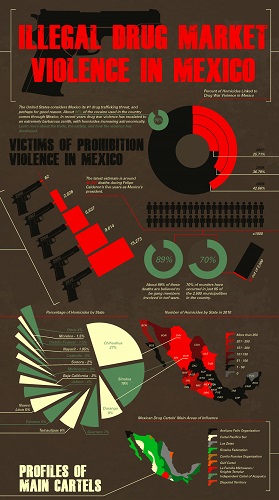

Illegal Drug Market Violence in Mexico

Factors that have contributed to the rapid rise in crime in Mexico include the transitional nature of the political situation, which is further compounded by internal transformations in the country, which was in transition to a multiparty system from a single-party system with its political monopoly of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Over its seventy years in power the PRI forged an alliance with drug cartels that acted with impunity thanks to local governors and police bosses, while the country continued to be perceived as a stable and democratic state.

While Mexico has had OCGs, in the form of family drug cartels and smuggling gangs since the 1930s, in the late 1990s their form and mode of operations changed as they started aggressively expanding their activities looking for more lucrative gains. They added various types of contraband to their already existing operations of drug production and trafficking: trafficking in fire arms, trafficking in illegal migrants, extortion, human trafficking supplying "human goods" to the sexual services market, software theft, etc. The most powerful OCGs continued to deal in drug trafficking, using violence to eliminate competition and secure drug trafficking routes. In 2000-2009, incidents of drug trafficking related crime increased 260 percent from 24,950 to 63,404. The abrupt increase in criminal activity resulted from the spread of drugs among the population and the growing volumes of trafficking activity carried out by the OCGs involved in the illicit drugs business. In 2009, 18,900 murders were committed, putting Mexico in sixth place in the world. In 2011, organized crime was responsible for 15,000 murders, 84 percent of which were recorded in the following four states of the country: Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Tamaulipas, and Guerrero. The five most violent cities were: Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Culiacan, Tijuana, and Acapulco. Weak government and critical deficiencies in governance have been highlighted by scandalous revelations implicating senior policemen in drug trafficking. In October 2008, the former head of the Mexican anti-drug agency, Noe Ramirez, was arrested following the disclosure of his links to the Sinaloa drug cartel, which paid him U.S.$ 450,000 per month for information on forthcoming police raids.

An immediate and tangible threat to national security, apart from the north border with its explosive situation, comes from organized crime groups that branch off to formerly unaffected areas in the country. Factors that have contributed to the rapid rise in crime in Mexico include the transitional nature of the political situation, which is further compounded by internal transformations in the country, which was in transition to a multiparty system from a single-party system with its political monopoly of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Over its seventy years in power the PRI forged an alliance with drug cartels that acted with impunity thanks to local governors and police bosses, while the country continued to be perceived as a stable and democratic state. The National Action Party (PAN), which came to power in 2000, undermined this coexistence of criminals and authorities at all levels, propelling OCGs to an unprecedented level of activity together with the increasingly frequent use of violence in pursuit of their “business interests,” retaliation against their competition, and safeguarding trafficking channels. Cartels, hitherto loyal to the authorities, threw down the gauntlet to the government and society.

Functioning as illegal firms infiltrating the sphere of legal business, criminal organizations today are multi-tiered structures. They have an army of assassins, "mules" and musclemen who support trafficking, safeguard illicit cargoes and neutralize competing gangs or law enforcement agencies. The most influential members of organized criminal groups control hubs and numerous cells of their business networks that remain unknown to law enforcement.

The pervasive corruption that affects authorities at all levels is a fertile breeding ground for crime and criminals. Public trust in law enforcement has been undermined following the scandalous exposure of senior police officers as implicated in drug trafficking. Little has changed since the 2009 General law on the national system of security requiring that security officers are appraised every four years. In 2010, Mexico registered a record high level of corruption, which since 2007 grew 18.5 percent, while bribes totaled 32 million peso (U.S.$ 2.75 bln). That year, Mexico dropped from 56th place to 98th (between Egypt and the Dominican Republic) in Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index, and in 2012 fell further – to 105th place (between Mali and the Philippines). For comparison, Russia is ranked 138th in this index, between Uganda and Azerbaijan.

Government's Response to Drug Cartels

Rafael Cedeño González, alias “El Cede,” of

the Familia Michoacana cartel, Mexico City,

19 April, 2009

The criminal offensive and unprecedented growth in violence urged the government of Felipe Calderon (2006-2012), who could not trust corrupt police in states and municipalities, to rely on the army and navy to defeat drug mafia. While they proved effective in conducting arrests and eliminating some cartel leaders as well as in boosting the volumes of drug seizures, the outcome of this war on drugs has been mixed. First, the army owed its success in many ways to the intelligence they got from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and the assistance the Americans provided in training specialist anti-drug units. Secondly, the fact that the apprehended drug barons were extradited to the U.S. indicates the extreme weakness of local law enforcement and corruption of Mexican penitentiary officers, who have allowed criminal bosses to escape from local prisons. Thirdly, the authorities were caught unawares by the emergence of anti-army sentiment among the general public that challenged the alleged successes of the security agencies and the casualties (57,000 people) as the price the country has to pay for the illusory achievements of the war on drugs.

Neither the Mexican authorities that hope to continue to coexist with the criminal clans nor the U.S. is in any position to design a strategy to disrupt the TOC groups active regionally or sometimes globally. There is little chance that this strategy will work, although both presidents have reaffirmed their willingness to continue anti-crime cooperation.

The high price in casualties of President Calderon’s anti-drug strategy was one of the reasons for the changing loyalty among the voters. During the 2012 election they refused to support PAN and brought to power the PRI leader Enrique Peña Nieto who does not seem eager to continue putting violent pressure on major drug traffickers, but prefers instead to bargain with them in order to bring down the level of violence in their respective zones of operation. Neither the Mexican authorities that hope to continue to coexist with the criminal clans nor the U.S. is in any position to design a strategy to disrupt the TOC groups active regionally or sometimes globally. There is little chance that this strategy will work, although both presidents have reaffirmed their willingness to continue anti-crime cooperation.

Drug Trafficking Going Global

In contrast to heads of states or governments who might procrastinate over the most urgent decisions, criminals are quicker to adapt themselves to financial and economic globalization, exploiting a variety of strategies to expand their illicit business. One side effect of the Mexican war on drugs was the accelerated spread of cartels and their expansion into neighboring countries of Guatemala, Belize or Honduras, where the weak governments are in no position to counter criminal gangs based in Mexico and their pursuit of extensive links with Latin American, Asian or African criminal groups.

The proximity of the North American market has been a powerful impetus to collaboration between Mexican and Columbian criminals, which have merged into a resilient TOC group enjoying the patronage of local law enforcement agencies, in particular state and municipal police. Municipal police chiefs get between 40,000 to 300,000 peso from their partners in crime. Easy gains brought some police officers into the fold of criminal gangs. The temptation proved too strong even for military service-people who had undergone special training. They deserted the force to set up their own gangs underneath the OCGs, evolving over time into proper local cartels. This was exactly how the Zetas Cartel developed, infamous for its unparalleled cruelty, graphically highlighting the erosion of the Mexican state.

The established links between Mexican and Columbian cartels started to shift in the mid-2000s. It is the Mexicans who set the rules now, with their distribution networks in America, and who control trafficking routes and supplies of illicit drugs to the U.S. and other countries. Developments in Mexico and Columbia show that, even if defeated, major drug barons remain in the criminal world, resurfacing under new aliases. The Mexican crime map now includes a new generation of gangs capable of adjusting smoothly to the changing internal and external environment, such as the Jalisco New Generation or Acapulco cartels or chapters of the Michoacán Family (FM).

Alliance of Government and Crime

Transnational organized crime employs IT engineers and bank staff, chemists, hackers, and, in addition to their private armies and financial capacities, their links with the executive, legislative and judiciary authorities in Mexico, and increasingly broad ties with the OCGs in Europe, Asia and Africa has led to rapid transformations in Mexico's criminal world, challenging the institutions of power. These developments should serve as a warning to Russia’s security agencies.

The leaders of the Michoacán Family, created in 2006, use bribes to establish ties with public officials at all levels in order to get access to whatever information they may need. This is one way the drug mafia undermines the government. In 2011, 35 municipality heads were apprehended for alleged links to the FM, but all had been freed by 2012, further demonstrating the extent of corruption in courts. Today, it is not unusual for municipality heads to lead the newly-created gangs. The extent of criminal clan penetration is further evidenced by the fact that for 10 years the Columbian drug baron Leon Montoya from the Norte del Valle Cartel, enjoyed the protection of the Mexican Federal police.

Transnational organized crime employs IT engineers and bank staff, chemists, hackers, and, in addition to their private armies and financial capacities, their links with the executive, legislative and judiciary authorities in Mexico, and increasingly broad ties with the OCGs in Europe, Asia and Africa has led to rapid transformations in Mexico's criminal world, challenging the institutions of power. These developments should serve as a warning to Russia’s security agencies.

Vladimir Sudarev:

Mexico and Russia in Search of New Areas

for Cooperation

A step in the right direction came on October 15, 2012 when Yuri Fedotov, Executive Director of the UN Office on Crime and Drugs, and Secretary of State of Mexico Dr. Alejandro Poiré Romero signed an agreement on cooperation in the ongoing effort to counter TOC and drug trafficking. It offers a chance to broaden contacts with Mexico. At the same time, the United Nations, Latin American observers and statesmen all concede that the U.S. anti-drug strategy has failed. In effect, recent decades seem to suggest that banning the production, consumption and trafficking in drugs, and subjecting those involved in this criminal chain to criminal prosecution, cannot either limit supply or reduce the consumption of illicit drugs. Consequently, the predominantly prescriptive approach has lost its popularity, judging by the popular debate over alternative policies, the legalization of light drugs and decriminalization of their trade. It may lead, in the near future, to a change in the overall paradigm of drug policy, shifting the focus from the use of force against the drug threat to reducing the concomitant injury to public health in Latin America.

****

Given the transboundary nature of organized crime, and the imperatives of multilateral intergovernmental cooperation to fight this plague of the 21st century, on the one hand, and today’s socio-political and criminal situation in Mexico and Russia, on the other, any proposed cooperation between the two countries’ security agencies would appear dubious and inappropriate. Both countries face increasingly aggressive criminal organizations, while the state is growing weaker, and both law enforcement and penitentiary authorities seem highly inefficient. With access to various spheres of legal business and in view of the pervasive corruption, criminals easily penetrate executive authorities at the federal, regional or municipal level. Any prospects for joint efforts limiting transboundary crime are substantially limited due to the flaws in Russian and Mexican legislative frameworks and the lack of funds that the two countries need to upgrade their police and armies’ weapons and monitoring equipment.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |