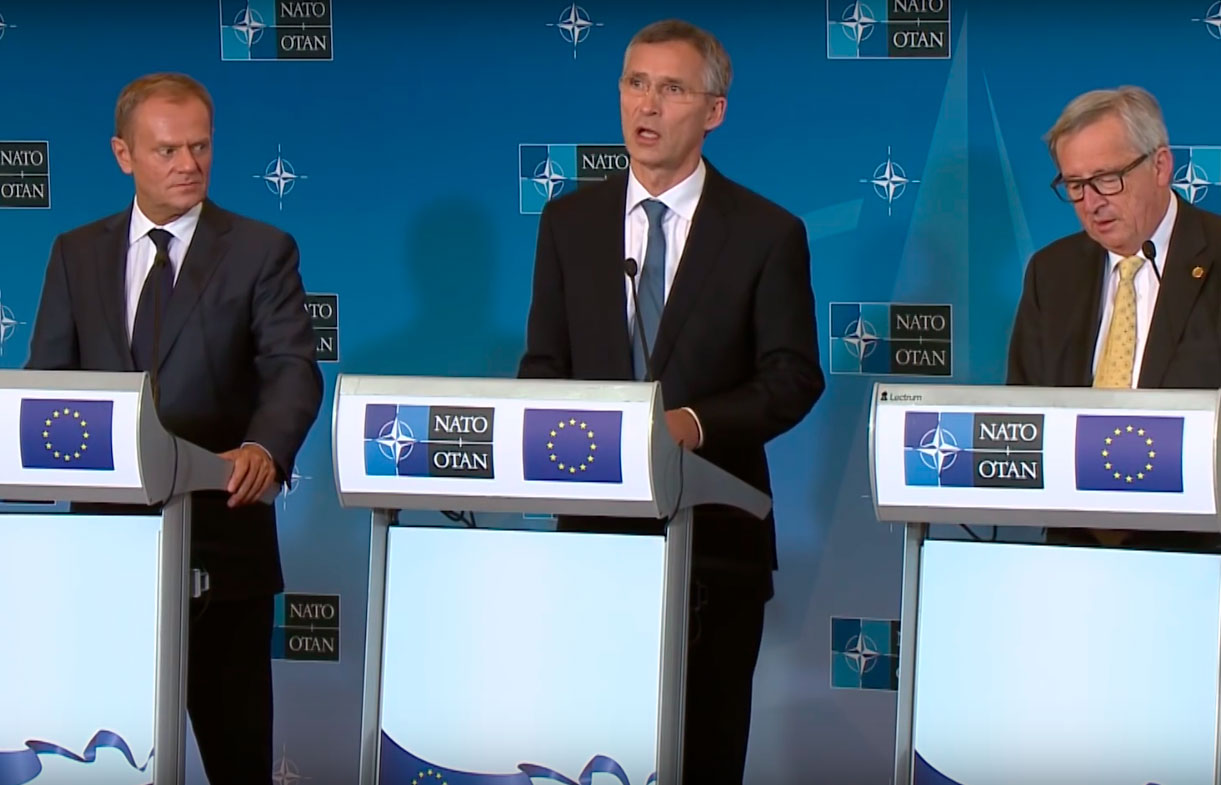

At the NATO summit in Warsaw on July 8–9, 2016, particular attention was paid to the issues of the Alliance’s activity in cyberspace. NATO adopted a “Cyber Defence Pledge” which contains a development plan. What is more, NATO once again confirmed certain political aspects of its activities in this area, described in more detail in the Warsaw Summit Communiqué. In particular, cyberspace was recognized as a “domain of operations in which NATO must defend itself as effectively as it does in the air, on land and at sea.” The decision to expand cooperation with the European Union in cyber defence was reflected in the Joint Declaration signed by the President of the European Council and the Secretary General of NATO.

NATO’s New Digital Wall

The need for NATO to defend itself from cyber-attacks was discussed back in 1999, when hackers attacked NATO websites during its military operation in Yugoslavia. The first practical steps were taken at the 2002 NATO Summit in Prague, when the decision to enhance defence against cyber-attacks was adopted. Subsequently, a cyber defence programme appeared, which involved creating a NATO cyber-attack response capability.

When the governmental bodies in Estonia (2007) and then Georgia (2008) suffered cyber-attacks, NATO adopted its first ever cyber defence policy, revised in 2011. The 2008 Bucharest Summit Declaration stated that the cyber defence policy “emphasises the need for NATO and nations to protect key information systems in accordance with their respective responsibilities; share best practices; and provide a capability to assist Allied nations, upon request, to counter a cyber attack.” Special attention was also paid to strengthening links between NATO and national authorities. The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence was established in Estonia for joint defence against cyber-attacks. According to the Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (2010), ensuring the security of cyber systems is one of NATO’s priorities. The Concept also emphasizes the need to “develop further our ability to prevent, detect, defend against and recover from cyber-attacks.” The NATO Communications and Information Agency (NCIA) established in 2012 was in charge of creating a centralized cyber defence system.

In 2014, NATO endorsed an Enhanced Cyber Defence Policy mentioned in the Wales Summit Declaration. The policy states that Article 5 of the North Alliance Treaty is applicable to cyber space. In particular, the declaration states that “cyber defence is part of NATO's core task of collective defence.” It was decided that “a decision as to when a cyber attack would lead to the invocation of Article 5 would be taken by the North Atlantic Council on a case-by-case basis.” Despite this qualification, a dangerous precedent is being created: since it is difficult to determine the source of a cyber-attack, states that were not involved in it may be attacked. Thus, cyber-attacks on the Estonian and Georgian governmental bodies in 2007 and 2008 were initially attributed to Russia. Later, however, an independent investigation ruled out this information. The Summit’s participants recognized cyberspace as a domain of NATO’s operational responsibility, which entails creating command bodies and attracting the necessary financing and workforce.

Efforts are being consolidated in several areas. In early 2016, an agreement was signed between the NATO Computer Incident Response Capability (NCIRC) and the Computer Emergency Response Team of the European Union (CERT-EU). The agreement provides for exchanging technical information between these two bodies, which is intended to facilitate the detection, response to, and prevention of incidents in both bodies. The NATO – EU Joint Declaration signed at the Warsaw Summit also demonstrates the desire to work together. This cooperation could be viewed as something more than just an attempt to bring together cyber-attacks detection and response capabilities; it could also be viewed as an attempt on the part of NATO to optimize expenses for defending strategically important national infrastructure and shift the burden onto the states themselves while retaining NATO’s standards and approaches. Attracting private businesses into developing cyber defence is another way to optimize expenses, and it is gaining ever greater popularity around the globe.

In July 2016, NATO announced its plans to spend 3 billion euros on cutting-edge defence capabilities, including 70 million allocated for a cyber-refresh. Invitations to take part in tenders will be sent out in 2017, and the first investment round will be completed by 2018.

The NATO Information Assurance and Cyber Defense Symposium took place in Mons (Belgium) on September 7–8, 2016; it served as a platform for links between NATO on the one hand and experts and representatives of companies working in cyber security on the other.

The Shaky Foundations of Cyber Defence

NATO’s cyber defence is based on several serious problems which, taken, together, may act as a destabilizing factor for international security as a whole.

Firstly, in its 2013 report, the UN Group of Governmental Experts stated “that international law and in particular the United Nations Charter, is applicable and is essential to maintaining peace and stability and promoting an open, secure, peaceful and accessible ICT environment.” However, there is still no answer to the question of how international law should be applied. NATO is preparing its answer to that question. The Tallinn Manual on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Warfare 2.0 is set for release in 2016; the manual is a revised version of the 2013 document. The new edition prepared by the international law experts commissioned by NATO and created under its auspices pays special attention to the application of the general norms of international law (sovereignty, jurisdiction, due diligence and the prohibition of intervention) in the cyberspace domain. The first edition failed to solve an entire series of issues; in particular, it failed to address the issue of what cyber-attacks are under international humanitarian law. And there are no mechanisms for their attribution. This means that charges of carrying out a cyber-attack can be levelled without any substantial proof, which has happened many times. At present, we do not know what the experts are going to suggest in the Tallinn Manual 2.0, yet the attribution problem has not yet been solved technologically.

Secondly, enhancing NATO’s cyber capabilities may lead to the spread of specialized ICT tools, i.e., cyber weapons. Many NATO countries have already incorporated provisions validating the right and necessity to develop such special means into their doctrines. For instance, the United Kingdom’s second Cyber Security Strategy presented in 2011 declares the need to develop a proactive approach to cyber defence. In the same year, the UK Secretary of State for Defence said, “The UK is developing a cyber-weapons programme that will give ministers an attacking capability to help counter growing threats to national security from cyberspace.”

The Wales Summit Declaration states the need to further develop national cyber defence capabilities and enhance the cyber security of the national networks upon which NATO depends in carrying out its core tasks. That means that in the future, all NATO members can either have attack and defence capabilities in cyberspace and possess appropriate technologies, or they can host such capabilities and technologies, much like Europe hosts U.S. nuclear weapons. Cyber weapons have low “entry threshold,” they can be developed without a powerful industry or an academic foundation. The simplest of attacks can be carried out using regular computers with internet access. Mercenary hackers are ready to offer their services to paying customers. A more powerful attack directed against critically important infrastructure requires larger resources and lengthy preparations by a team of professionals using models of systems under attack, but it costs significantly less than developing nuclear weapons [1]. In the computer age, virtually any country can become a superpower in cyberspace.

NATO’s current policies in cyberspace are based on defence and deterrence. The Alliance’s experts study various options of such deterrence. Yet when considered in detail, it turns out any analogies with “traditional” deterrence applicable to the real, physical world, are irrelevant in the virtual world. Nuclear deterrence entails the possibility of a retaliatory strike, and there is a whole range of tools that allow the aggressor to be determined. Even though such tools are being rapidly developed for cyber-attacks, they are virtually unusable. When talking of a symmetrical retaliatory strike, it should be noted that cyber weapons cannot be seen, much less qualitatively and quantitatively measured using any direct methods. As some experts note, while nuclear deterrence entails a demonstration of power, in cyber space, demonstration is replaced with the effects of using the weapons [2]. The known instances of using cyber weapons (for instance, a strike against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure facilities with the Stuxnet virus) can give an idea of their possible effects and effectiveness. As of today, we have no examples of any state openly using cyber weapons, and cyber-attack deterrence is based, among other things, on the policy of responding to cyber-attacks by any means available, from sanctions to military action (depending on damage sustained). When the source of a cyber-attack is hard to determine, such an attack may lead to escalating tensions or serve as a cause for retaliatory measures.

NATO’s Cyber Defence Tomorrow

Considering the dynamics of NATO cyber defence development as a whole and drawing parallels with similar processes in individual states, primarily in the United States, we can distinguish certain trends.

The development of U.S. cyber defence policy has gone through several stages. Initially, just like NATO, it had as its core task ensuring the security of military networks and systems. In 2001, cyberspace was officially recognized as a new battle ground. In 2010, Cyber Command became operational; it had the following tasks: conducting defence and attack cyber operations; defending military systems and networks; and coordinating cyber defence links between all branches of armed forces. The United States possesses appropriate specialized ICT tools (cyber weapons), which has been confirmed several times, including by U.S. officials. The issue of the applicability of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty to cyberspace was discussed at the 2010 Atlantic Council meeting. The main participant was Hillary Clinton, then United States Secretary of State. In particular, she stated that such threats to NATO’s computer networks and infrastructure as cyber-attacks should be considered from the point of view of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty.

At the 2014 Wales Summit, NATO recognized the applicability of Article 5 and then declared cyberspace its sphere of responsibility. We should not rule out the possibility of new plans to create a NATO Joint Cyber Command being announced at the next summit to be held in Belgium in 2017. The prospects of such a decision will hinge, among other things, on the outcome of the U.S. presidential elections.

In order to carry out full-fledged cyber defence, it is necessary to solve the deterrence and attribution issues. It is also necessary to determine the universal format for applying international humanitarian law to actions unfolding in cyberspace. If these issues are not resolved, a build-up of cyber capabilities could have a negative effect on international security. Russia and several other states adhere to the position of recognizing the need for limiting, and ultimately prohibiting, the use of cyber weapons as a tool that undermines international stability. A certain consensus on the issue has been achieved within the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and BRICS. The Basic Principles of the State Policy of the in the Field of International Information Security Until 2020 state that the conditions need to be created for the establishment of an international legal regime of non-proliferation of information weapons as one of the means for decreasing the risk of using ICT when carrying out hostile actions and acts of aggression.

1. The Brookings Institution estimates that the Manhattan project cost about $25 billion (in 2014 prices). See: The Costs of the Manhattan Project // The Brookings Institution (https://www.brookings.edu/book/atomic-audit/). To compare, Fortinet estimates that creating a Zeus-type botnet costs upwards of $700 (https://www.fortinet.com/content/dam/fortinet/assets/white-papers/wp-ctap-threat-landscape.pdf)

2. Thomas T. L. The Dragon’s Quantum Leap: Transforming from a Mechanized to an Informatized Force // Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO). Fort Leavenworth, KS (2009).