Europe Under Fire from US Secondary Sanctions

(votes: 4, rating: 4) |

(4 votes) |

PhD in Political Science, Director General of the Russian International Affairs Council, RIAC member

As Washington has dramatically increased the use of sanctions, the EU has had to keep up. Naturally, US and EU sanctions are not always identical, but their largely shared political positions and allied relations ensure that political steps, including sanctions, are coordinated. This is the case, for example, in relation to Russia.

At the same time, the US remains the leader in imposing unilateral economic sanctions. Washington leads both in the number1 of sanctions and the sheer might of the government machinery involved in enforcing them. The Americans have amassed an enormous amount of experience and acumen in this regard, taking advantage of their powerful economy and unique standing in the global financial system. The dollar’s dominance in world financial transactions enables the US authorities to monitor a huge number of financial transactions, identify breaches of US sanctions programmes, and punish violators with secondary sanctions.

Secondary sanctions target companies, states, or individuals that do business with sanctioned countries, organizations, or individuals. ‘Sanctions for violating sanctions’ are used against US citizens and companies, as US laws are applicable only within US jurisdiction. During the past three decades, however, such sanctions are increasingly exterritorial in application, hitting companies and organizations from numerous other countries. The fact that exterritorial sanctions are possible at all is due to the dominant position of the US financial system in the context of international financial transactions and the close links that many major companies have with the US market. All foreign players who have some degree of relationship with US financial institutions, companies, or markets come under US national law. Apart from purely economic benefits, this global economic role gives the Americans powerful political leverage.

There are several reasons why the European Union is increasingly proactive in applying economic sanctions. First, the EU has emerged as one of the largest global economies with vast technological, industrial, and human resources. Second, the foreign policy tools used by Brussels are traditionally economic and based on soft power. The EU’s limited military and political capabilities make sanctions a particularly promising foreign policy tool. Third, the EU is bound by a relationship of strategic interdependence to the United States, often joining US sanctions to some extent. As Washington has dramatically increased the use of sanctions, the EU has had to keep up. Naturally, US and EU sanctions are not always identical, but their largely shared political positions and allied relations ensure that political steps, including sanctions, are coordinated. This is the case, for example, in relation to Russia.

At the same time, the US remains the leader in imposing unilateral economic sanctions. Washington leads both in the number [1] of sanctions and the sheer might of the government machinery involved in enforcing them. The Americans have amassed an enormous amount of experience and acumen in this regard, taking advantage of their powerful economy and unique standing in the global financial system. The dollar’s dominance in world financial transactions enables the US authorities to monitor a huge number of financial transactions, identify breaches of US sanctions programmes, and punish violators with secondary sanctions.

Secondary sanctions target companies, states, or individuals that do business with sanctioned countries, organizations, or individuals. ‘Sanctions for violating sanctions’ are used against US citizens and companies, as US laws are applicable only within US jurisdiction. During the past three decades, however, such sanctions are increasingly exterritorial in application, hitting companies and organizations from numerous other countries. The fact that exterritorial sanctions are possible at all is due to the dominant position of the US financial system in the context of international financial transactions and the close links that many major companies have with the US market. All foreign players who have some degree of relationship with US financial institutions, companies, or markets come under US national law. Apart from purely economic benefits, this global economic role gives the Americans powerful political leverage.

Despite its economic clout and growing number of sanctions programmes, the EU is still no match for the US in terms of leverage. More than that, EU companies themselves often fall under US sanctions. It is relatively rare for the Americans to put European companies on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List (SDN List) of entities that it is illegal to do business with. However, the US Treasury Department often fines transgressors. Moreover, EU companies constitute the overwhelming majority of fined foreigners over the last ten years, and it is European companies that have paid the biggest fines to the US Treasury.

The European Union has been attempting to do something to protect itself from US secondary sanctions since at least the early 1990s. A powerful incentive was furnished by the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on the Iranian nuclear programme. Washington has unilaterally resumed large-scale financial and sectoral sanctions against Iran. As a result, a large number of companies operating on the Iranian market, including European firms, are threatened with secondary sanctions and subsequent fines. The EU has reintroduced the so-called Blocking Statute (1996) supposed to protect European companies from secondary sanctions. But numerous EU companies have already left Iran.

We are witnessing a situation where major European companies have opted to defer to US demands despite the fact that Brussels was critical of the US withdrawal from the JCPOA and introduced protective measures. The threat of fines and expulsion from the US market and financial system has outweighed the promise of benefits offered by the Iranian market. This kind of logic is compelling for any country whose companies may fall under secondary sanctions.

Politically and militarily, the modern world has been multipolar for quite long. China, India, and Russia are strong centres of power in their own right and direct military aggression against them is simply impossible. But economically, the world remains unipolar. The US ability to use coercive economic measures is considerably higher than that of all other countries, and so major foreign companies involved in dollar transactions and reliant on the US market defer to American demands even where their own governments are critical of US actions.

This state of affairs gives rise to numerous questions. To what extent do secondary sanctions affect foreign businesses? What is the European share of companies hit by secondary sanctions? What measures are being taken by the European Union to protect its businesses and how effective are these measures? Is there any chance of the EU creating effective mechanisms or alternative financial systems to circumvent US sanctions? Are European businesses prepared to lobby for these changes? How accommodating are these businesses to US authorities? Can any other major economy, such as China, assume responsibility for effecting these transformations? Who will be able or even willing to challenge US hegemony in the area of sanctions? Are there chances for projects of this sort in the short term?

What Are Sanctions?

Sanctions are restrictions introduced by one or several initiators against a targeted country or group of countries. They are a tool of coercion used in an effort to force the targeted country to change its foreign or domestic policy under the pressure of trade and financial restrictions. Sanctions should be distinguished from trade wars. Trade wars are often aimed to make national producers more competitive with the aid of tariffs, subsidies, prohibitive duties, etc., whereas sanctions are economic tools designed to achieve political ends like regime change, military containment, punishment of certain politicians or organizations, etc. The range of economic measures is also different in this case and includes asset freezes, bans on financial transactions, curtailment of exports and imports, and sectoral restrictions. Naturally, businesses can benefit from sanctions. Yet, business interests are of secondary importance to political goals for government agencies engaged in crafting sanctions.

Sanctions can be compared to natural disasters. You are unable to influence a disaster but have to bear its consequences. As distinct from trade wars, businesses rarely lobby for or initiate sanctions, but their consequences affect everyone. In legal terms, sanctions and the tools of trade wars are also clearly differentiated, at least in the United States, which imposes sanctions more often than all other countries and international organizations combined.

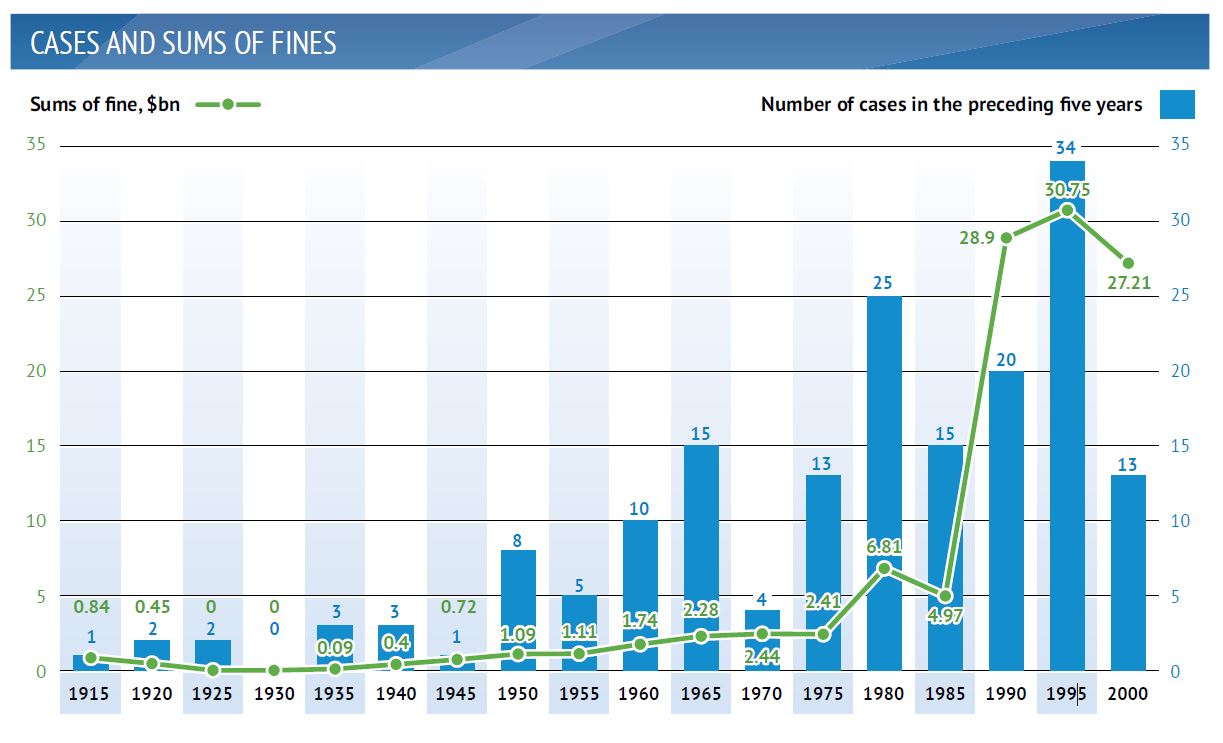

Sanctions have gone through much change in the past three decades. Prior to the end of the Cold War, initiators of sanctions mostly relied on all- out trade embargoes. This, for example, was what happened to Iraq in 1991. However, so-called ‘targeted’ or ‘smart’ sanctions came into vogue in the mid- 1990s and persist to this day. Sweeping trade restrictions are replaced by restrictions on individuals (e.g. high-ranking government officials, business leaders or ‘securocrats’), specific companies, or economic sectors. [2] In theory, this approach is meant to reduce the costs for a country’s population and bring more pressure to bear on its political elites. Iraq’s experience shows that sanctions do curtail targeted country’s resources but hit the most vulnerable groups rather than elites.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Human rights and concern for the populace, however, were not the only motivations for the increasing use of targeted sanctions. The latter were potentially more effective owing to the new realities emerging in the world financial system, which has become global and simultaneously more transparent for the US government – based on the dollar’s prevalence in global financial transactions. Financial sanctions have emerged as a more effective tool than trade embargoes. Possessing greater information about financial flows has made it easier to enforce trade restrictions. Financial sanctions have become akin to high-precision weapons and have increased the scope of secondary sanctions. Now sanctions were able not only to punish the ‘main targets’. The threat of secondary sanctions can make the targeted country – or specific companies, or even individuals – ‘toxic’. A transparent financial system would clearly reveal all transactions with sanctioned individuals, with all the attendant problems such as investigations by US regulators, fines, and/or blacklisting. On the one hand, transparency has resulted in unprecedented capabilities for fighting financial crime, money laundering, and terrorism. The 9/11 terror attacks provided a powerful impetus for progress in the area of financial intelligence and bank transparency. On the other hand, the US government has acquired leverage to influence foreign companies for political purposes. Internationalizing US law has expanded the reach of secondary sanctions, thus boosting the damage done by ‘primary’ sanctions.

Primary’ or direct sanctions are restrictions introduced against individuals, companies, organizations, or economic sectors for political reasons. In the United States, the imposition of sanctions is a presidential prerogative. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act [3] authorizes the president to introduce sanctions after declaring an emergency over a certain issue. Normally these decisions are formalized by presidential executive orders. A list of sanctioned individuals or legal entities can be incorporated directly in the executive order, or the president can empower the appropriate agencies – the Department of the Treasury in cooperation with the Department of State and others – to compile a list on their own.

Making lists is an ongoing and routine process that depends on the receipt of new information or political briefs. Congress can also initiate and impose sanctions in the form of new legislation, which requires the executive to enforce sanctions and report to Congress on enforcement. The administration is left a considerable leeway, and often the executive introduces sanctions ahead of specified timeframes. But repealing or amending legislation is a much lengthier and more difficult process than revising presidential executive orders. Not infrequently, there are disagreements over sanctions between the administration and Congress, with the latter capable of reinforcing or preventing the modification of sanctions. A case in point is the controversy over lifting sanctions against Iran in 2015.

The Treasury Department is directly responsible for administering sanctions policy. Primary sanctions usually mean that individuals, companies, or organizations are put on one of several blacklists. The SDN List is the most formidable of all, as it bans US citizens as well as anyone operating under US laws (including any foreign company engaged in dollar-denominated bank transactions) from entering into economic, trade, or investment relations with the entities on the list. The lesser evil is the Sectoral Sanctions Identifications List (SSI List) of companies affected by sectoral sanctions, which often prohibit only a limited number of transactions. The most recent innovation is the List of Foreign Financial Institutions Subject to Correspondent Account or Payable- Through Account Sanctions (CAPTA List) of financial organizations that cannot have correspondent accounts in the United States. So far, it includes just a few Secondary sanctions are restrictive measures directed against violators of existing sanctions regimes. To punish these companies or individuals, the US Department of the Treasury can put them in the SDN List, as was the case with a number of Chinese and Russian companies suspected of maintaining economic ties with North Korea. [4] In other words, violators of the sanctions regime are treated the same as primary targets. This is the most severe punishment.

Monetary fines are another widespread punishment.At first sight,it is more lenient because it does not restrict a company’s economic activity. But the size of fines can be truly staggering. While the SDN often includes repeat violators or companies specially designated for working with a sanctioned country, fines are imposed on both highly profitable and respectable global companies and small firms caught in small deals. Fines are the most universal and flexible tool of secondary sanctions. [5] They are designed to teach the violator a lesson and deter future deals with sanctioned entities, while not shutting down its economic activity. The use of fines is an important measure of secondary sanctions, and it is European companies that suffer from fines the most.

Fines on European Businesses

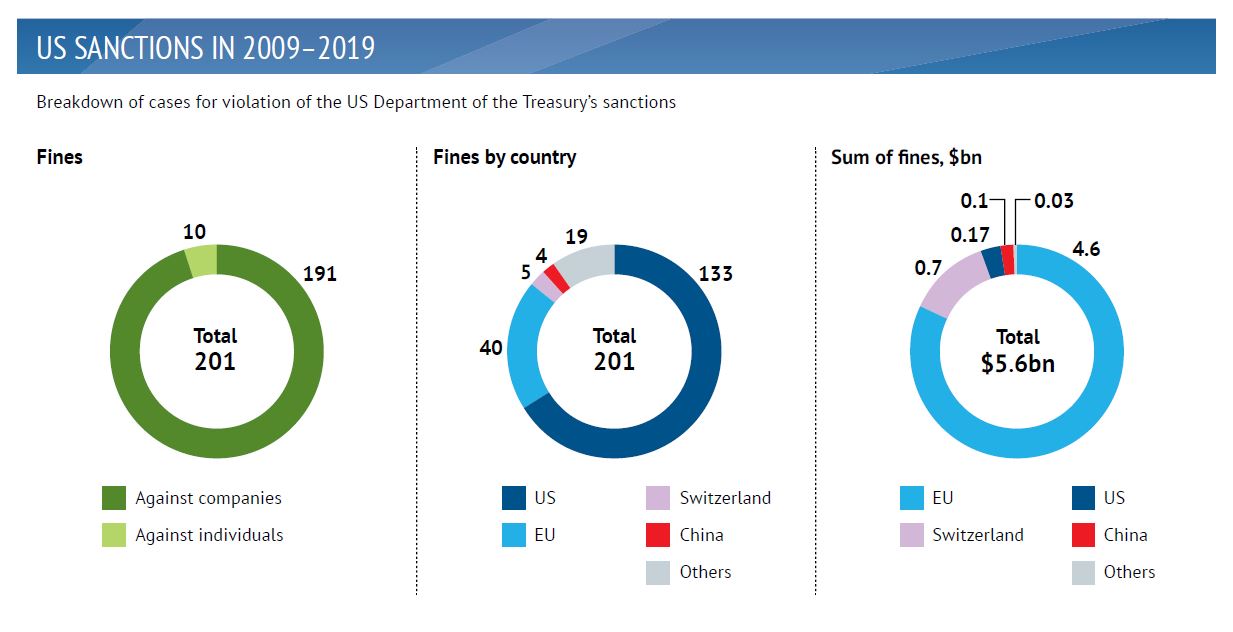

Over the last decade (2009–2019), the US Department of the Treasury has fined 191 companies and ten individuals for sanctions violations (the Russian InternationalAffairs Council’s assessments are provided hereinafter),for combined 201 cases. The amount of fines paid to the Treasury totalled $5.6bn. The actual payments are much higher, as, in some cases, in addition to the Treasury, other regulators, such as the Department of Justice or the Department of Commerce, issued claims against certain companies as well. In most cases, 133 out of 201, fines were imposed on US citizens and companies. In other words, ‘sanctions for violating sanctions’ are used mainly against Americans themselves. However, 68 cases (34%) concern investigations of foreign nationals, the overwhelming majority of which are European companies. The EU accounts for 40 cases (20% of the total) plus five more proceedings involving Swiss companies.

Source: US Depatrment of the Treasury.

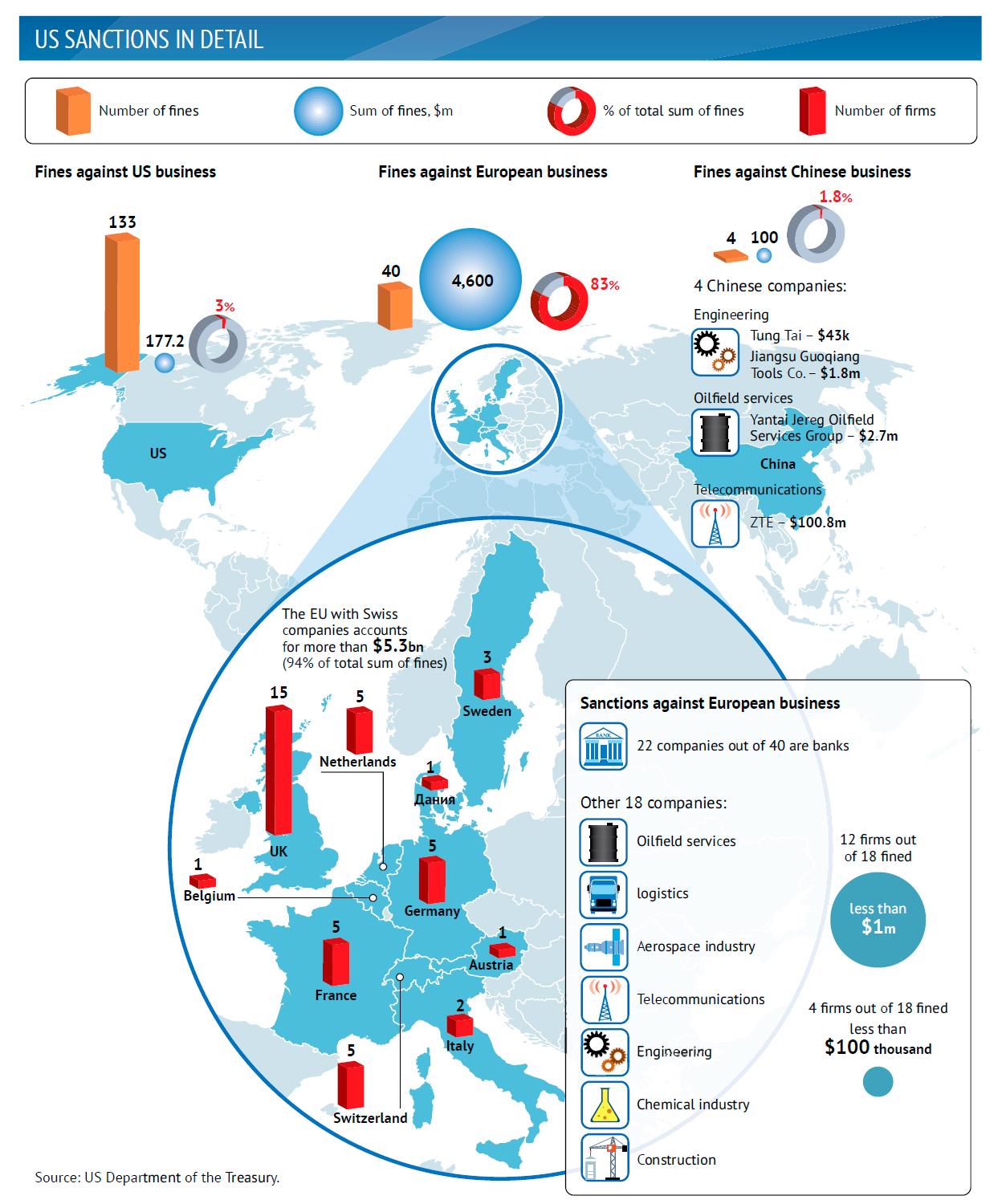

The European cases are distributed quite unevenly. British firms have paid 15 out of 40 fines. Germany, France, and the Netherlands account for five fines each. Swedes have paid fines three times, Italians – two, and Danes, Belgians, and Austrians – one each. A company from Luxembourg paid a fine once as well.

More importantly, Europeans paid 83% of the total amount of fines, or over $4.6bn. If you add Switzerland to the EU, their aggregate share amounts to 94%, or over $5.3bn. Despite a large number of cases, US companies collectively paid only 3%, or $177.2m. In other words, the EU and Switzerland together account for the bulk of payments. This distribution is close to the Pareto principle where most of the revenue is generated by a minority, which, in this case, is concentrated in Europe. A smaller share of payments comes from the majority – based in the United States. Obviously, such a distribution is hardly the product of deliberate actions by the US authorities. But the fact remains that the Europeans have paid more than anyone else.

Source: US Depatrment of the Treasury.

Notably, 22 of 40 EU companies are banks, which paid the US Treasury the bulk of the European fines, namely, more than $4.5bn over ten years. So far, the French BNP Paribas Bank has been the undisputed champion in this regard with a little over $963m wired to the US Treasury in 2014. [6] The British Standard Chartered Bank with over $650m, as well as the German, Austrian, and Italian branches of the UniCredit Bank ($611m) almost broke this record in 2019. In 2012, the Dutch ING Bank paid $619m. The British HSBC was forced to pay $375m that same year. The average amount of a fine paid by European banks over ten years exceeded $208m. Indeed, some fines were relatively small. For example, the French bank Societe Generale was hit with a fine of $53.9m in 2018, compared to just $111,300 in 2011.

Why do banks pay much more than other players and why do they constitute the main target? There are both subjective and objective reasons for that. The subjective side of it is that banks deliberately ignore US laws, as they try to hide the presence of sanctioned countries or entities in their reporting. Of the 22 cases with European banks, 13 were classified by the US authorities as ‘egregious’. That is, the banks, at the very minimum, turned a blind eye to US sanctions and, at the most, acted wilfully in attempts to conceal their transactions to turn a profit. Usually, the banks’ management were aware of such violations. In such cases, banks do not voluntarily report themselves to the Treasury and are considered ‘caught’ in violation of the rules. The largest fines are usually paid for violations of this kind. Wilful intent, negligence, involvement of management, refusal to come clean, inadequacy of compliance programmes and other factors are seen by the Americans as aggravating circumstances and tend to increase the size of fines.

However, there are also objective reasons for banks’ vulnerability. First, they perform a vast quantity of transactions that are not easy to monitor. A sanctioned client may well worm its way into billions of transactions. Banks are constantly improving their monitoring and control systems. But they can falter and commit errors. Unlike other industries, where one or two programmes are generally violated, banks simultaneously violate four to five or even more. Since fines are calculated on the basis of the number of transactions and their volume (they can be really big with banks), the size of fines paid by the banks is much larger than by companies from other industries. Bank managers can make wrong decisions unintentionally. Illegal transactions can be carried out by subsidiaries unbeknownst to the head office. In such cases, both US and European banks often report violations themselves and receive significant discounts on fines. The average fine paid by a European bank for a non-egregious violation amounted to only $3.4m over the past decade, compared to $303m, or 100 times more, for an egregious violation.

Pressure on Huawei Will Spell Doom for American Business

Regardless of the severity and nature of a violation, all banks have one thing in common. If a US regulator starts an investigation, banks are often as accommodating as possible of requests coming from the United States and tend to cooperate with the investigative authorities. Moreover, they go to great lengths to convince the Treasury and other regulators that such violations will not happen in the future. Their legal and compliance departments hire more staff, funds are allocated for auditing transactions and purchasing transaction control software, and staff training is conducted, among other things. In other words, European (and American) banks demonstrate high levels of conformity with regard to requests issued by US authorities, as they seek to reduce costs and to avoid being involved in such investigations ever again. Symptomatically, there are no repeat offenders among violators. There are almost no cases where a company has been fined twice in a matter of five years.

Sanctions are imposed on companies from other industries as well. However, when it comes to Europe, it is rarer than in the financial sector. Also, no single industry stands out as the most susceptible to sanctions. There were 18 such EU companies in a matter of ten years, including oilfield servicing, logistics, aerospace, telecommunications, engineering, chemical, and construction companies. The fines they paid were infinitesimal compared to the fines paid by the banks. Overall, they paid the Treasury a little more than $90m, with 12 out of 18 companies paying a fine under $1m and four out of 18 – under $100,000. Only in five cases out of 18 did the US Treasury classify violations as ‘egregious’, which is noticeably fewer than in the case of banks. The Dutch company Fokker Services paid the largest fine in the amount of $50.9m in 2014 for supplying aircraft parts to Iran and re-exporting them to Sudan.The case was recognized as ‘egregious’ since, according to US authorities, the Dutch company acted wilfully and ignored US sanctions programmes. However, in other cases, the fines were significantly smaller.

Notably, ten out of the 18 European offenders from the non-financial sector were US firms’ subsidiaries. In such instances, the US-based parent company often voluntarily reported violations. This, for example, was the case with the German chemical company AplliChem GmbH, which is part of the US company Illinois Tool Works. In February 2019, the US Treasury Department imposed a $5.5m fine on it for supplying products to Cuba. Even though the regulator classified the violation as ‘egregious’ (the German company’s actions were deemed wilful), voluntarily reporting it led to a smaller fine. Otherwise, it could have theoretically reached $20m. Like banks, companies from other sectors are extremely accommodating of regulators’ requests during the investigation stage in an attempt to reduce the amount of their fine.

Iran-related violations are the most common cause of fines. Often, violations are related to Cuba, Sudan, and ‘functional’ programmes related to illegal drug trafficking or non-proliferation. However, there are quite unusual cases, too. For example, in December 2018, the US Treasury ordered the pharmaceutical company Zoltek to pay a fine of $7.7m for violating sanctions against Belarus, when a Hungarian subsidiary of Zoltek purchased raw materials from the Belarusian company Naftan.

With regard to sanctions on Russia, European companies have not paid yet a single fine for potential violations. This is partly due to the fact that investigations last many years, sometimes well over a decade. In other words, decisions made in 2019, for example, may well concern violations dating back to 2010 or even earlier. Russia-related fines may show up later. All the more so as three US companies have already been fined for such violations: Haverly Systems in 2019 ($590,200) for technical delays in accepting payments from Rosneft (the regulator saw this as a loan extended to the company which is illegal under the sanctions); Cobham in 2018 ($87,500) – for supplying products to the Russian company Almaz- Antey; and ExxonMobil in 2017 ($2m) – this time, again, for working with Rosneft’s top management.

As part of Russia’s energy sector, Rosneft faces only sector-specific sanctions and is not included on the SDN. Both cases involving it can be considered an overreach by the US authorities. ExxonMobil itself objected to the fine, deeming it unreasonable. Although the size of the fine was meagre in comparison with the scope of ExxonMobil’s operations, this case is quite unique as the Treasury imposed the largest possible fine, whereas in the vast majority of other cases the companies paid much less. All three episodes associated with secondary sanctions for violating restrictions imposed on Russia have shown that the US Treasury will be uncompromising in this regard, targeting disputable, unobvious, or minor violations.

European Counter-play?

American fines have not tended to cause problems in the relationship between Brussels and Washington. Businesses have generally refrained from politicizing the issue and, in all cases without exception, sought to satisfy the demands of the US authorities. At the political level, the Europeans have spoken out only when American sanctions threatened their strategic interests. This happened,for example,when the US tried to hinder the construction of Soviet gas pipelines to Europe. The EU also enjoyed success in the 1990s. The Clinton administration and the US Congress in 1995–1996 tried to internationalize their sanctions against Iran. The EU responded by introducing the so-called Blocking Statute, which aimed to protect European companies from US extraterritorial sanctions. While Washington refrained from imposing secondary sanctions against the Europeans at that stage, ultimately the Americans achieved significant success in advancing their sanctions approach. During the 2000s, the EU supported sanctions against Iran, North Korea, and a number of other countries, generally in synch with the US position. In the case of Iran, the EU played an important role in brokering the JCPOA, considering the agreement a major diplomatic victory. In sanctions policy, the US and the EU acted as allies. The Department of the Treasury’s battle with individual European companies did not overshadow the allied agenda.

The situation changed after the unilateral US withdrawal from the JCPOA in May 2018 and the re-introduction of all US sanctions that had been in force before the deal was reached in 2015. [7] The Trump administration demanded that Iran meet a number of Washington’s demands (Pompeo’s 12 point plan), [8] which amounted to Tehran’s capitulation on a number of its foreign policy priorities. Among the most sensitive sanctions was the ban on the import and transportation of Iranian oil, which the Americans extended to all buyers. That is, the sanctions were declared extraterritorial again.

The EU and the parties to the nuclear deal (UK, Germany, China, Russia, France, and naturally Iran) reacted harshly to Donald Trump’s demarche. For the EU, the undermining of the JCPOA was a sensitive issue both politically and economically. Brussels has long promoted the idea of multilateral diplomacy. Furthermore, when the main sanctions against Iran were lifted, European companies began to work actively on its market. This unilateral move of the United States derailed all such efforts. The Europeans tried to solve the problem in two ways. The first was to protect their companies on the Iranian market and create an alternative payment system to keep them off the US Treasury’s radar in the future. The second was to diplomatically support Iran and keep it in compliance with the JCPOA, despite the United States’ behaviour.

On May 17, 2018, nine days after Trump’s decision to withdraw from JCPOA, the Europeans announced the resumption of the 1996 Blocking Statute, a decision sealed by the European Council on August 7, 2018. [9] The document restricted the application of foreign sanctions in the EU. However, that had little influence on the strategies of large European companies. Major players such as Total, Siemens, Daimler, PSA Group, or Maersk Line chose to scale down their work in Iran. Major European businesses decided not to risk it. The price of losing the US market and possible fines by the US Treasury outweighed the loss of investment in Iran. In other words, global European companies continued to show deference to US law, despite the political and legal support from Brussels.

Certain politicians in Europe also spoke about the desirability of creating a European payment system in the interests of European sovereignty and financial independence. Statements of this kind came from Germany’s Foreign Minister Heiko Maas and France’s Minister of the Economy and Finance Bruno Le Maire in August 2018. In January 2019, the company INSTEX SAS was registered in France (with the participation of Germany and the UK) to secure European companies’ transactions with Iran, bypassing US sanctions. However, the fate of this initiative remains unclear. Its approval by other EU members is in doubt. The actual viability of INSTEX is uncertain. There is no reason why the Americans would not put INSTEX on their SDN List, thus rendering it ‘toxic’, or fine the company in proportion to the volume of its deals with Iran.

The prospects for INSTEX are becoming even hazier amid the diplomatic difficulties. After the US exit from the JCPOA, Washington found itself diplomatically isolated on the issue of Iran. However, this did not bother the Americans much, because their withdrawal from the deal confronted Iran with a difficult choice. One option was to resume its nuclear programme and face even more massive sanctions (this time involving the EU and UN) or maybe even the threat of a military strike. The other one was to continue maintaining its nuclear-free status despite the re-imposition of US sanctions. The situation began to heat up after the US ended exemptions for the purchase of Iranian oil, which applied to eight countries, including Italy and Greece. In May 2019, Tehran announced that it would stop meeting certain obligations under the deal. In response, Washington immediately introduced harsh new sanctions against Iran with respect to steel and metals. [10] The EU responded coolly to Tehran’s move. Now it seems to be Iran’s turn to be isolated.

The diplomatic developments around the JCPOA are likely to seriously undermine the European ambition to create an alternative payment system. If Iran becomes a rogue state again (as the Americans would like it to be), the very reason that gave rise to the discussion in the first place will vanish. As for the fines on banks and companies, Brussels is likely to leave these risks to the discretion of the businesses concerned. Moreover, business leaders have not made any serious attempts to lobby for such alternatives. Apparently, European business feel comfortable in the dollar system, and the risks of secondary sanctions do not outweigh the benefits from this system or the costs of transforming it. Moreover, outside of the Iranian problem, there are no sanctions that could lead to a serious discussion about a European financial alternative. The commonality of the US and EU political positions will ensure that the status quo continues.

Sanctions Policy: The ‘European Paradox’

A Chinese Alternative?

China is another major economy, and its companies are also subject to secondary sanctions. For this reason, China is viewed as one of the possible alternatives to the global financial dominance of the US. However, China’s case is somewhat idiosyncratic. First and foremost, China is not a US ally, and friction between Washington and Beijing has been on the rise lately as a result of the all-out trade war. Yet, its impact should not be overestimated. Trade wars are a common occurrence between partners. In this case, though, economic disputes add up to political differences and US concerns over China’s growing power, especially in the high technology sector.

China is not currently targeted by any specific sanctions programme. Back in 1989, China faced US sanctions after the Tiananmen Square protests, but most of the restrictions were lifted by the early 2000s against the backdrop of surging US–China trade. Although some residual sanctions still linger in the defence sector, China has been successful in offsetting these restrictions by buying from Russia.

That being said, it is not uncommon for Chinese companies to face secondary sanctions,and China’s case is quite different from European companies. First, SDN designations are a common occurrence for Chinese companies and individuals, with as many as 150 of them currently on this list. Most of them were listed for failing to comply with the sanctions against North Korea and non-proliferation efforts, and in some cases these sanctions were related to Iran or Syria. The SDN List mentions the Equipment Development Department of the China State Council’s Central Military Commission, which acts as a contractor in contracts with Russia to buy fighter jets and air defence systems. This institution was designated for violating Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), an act that Russia knows all too well. The list also contains branches of foreign companies operating in China.

This includes Belneftekhim, which has an office in Beijing and is also included in the programme of US sanctions against Belarus. The US also placed VEB Asia Ltd., a subsidiary of Russia’s Vnesheconombank (VEB), on the SSI list as part of sectoral sanctions against Russia.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry’s response when its entities or individuals appear on US sanctions lists is usually icy. Just like Russia, China believes unilateral sanctions imposed by Washington bypassing the UN Security Council to be illegitimate. Still, quite often China refrains from responding. So far there have been few Chinese companies on the SDN List, with almost zero economic effect on the overall Chinese economy.

The situation with fines against Chinese companies is quite similar, although, in comparison to Europeans, there are some interesting details worth mentioning. Over the past decade, only four Chinese companies were slapped with fines, ten times fewer compared to the EU. Unlike Europe, Chinese banks were spared. These penalties included a relatively harmless fine against the US office of Tung Tai, a company headquartered in Hong Kong, that had to pay $43,000 for failing to comply with Cuba sanctions, and this case was treated as a non-egregious violation, unlike the other three. In 2019, Stanley Black and Decker, a US company, came under sanctions, when its Chinese subsidiary, Jiangsu Guoqiang Tools Co., was accused of re-exporting industrial goods to Iran. This was a typical case against a subsidiary of a US company that voluntarily disclosed its wrongdoing to the Treasury Department in order to shave a significant amount off its fine. It ended up paying $1.8m instead of the $6.9m allowable under the law. In 2018, Yantai Jereh Oilfield Services Group, a Chinese oil equipment company, paid a $2.7m fine for re-exporting US goods to Iran. In this case, the company was ‘caught’ in violations and faced a fine ($2.77m) that was closer to the maximum penalty ($3.08m).

However, the case against ZTE, a Chinese telecom giant, was the one that resonated the most. In 2017, ZTE was slapped with more than $100m in fines by the US Treasury Department, while fines imposed by the US Commerce Department exceeded $1bn. The US believes that ZTE had been intentionally and covertly re-exporting goods containing US components to Iran in violation of sanctions. The fact that ZTE continued to violate sanctions after being ‘caught’ and agreeing to stop these deliveries made things even worse. As a result, the Treasury Department imposed a fine of $100.8m that was close to the maximum penalty of $106.1 m. The US has now turned its attention to Huawei. This case escalated beyond administrative proceedings, when in December 2018 the US requested that Huawei Technologies CFO Meng Wanzhou be detained in Canada. The political fallout from the claims against Huawei was exceptionally large for a case of this kind.

What sets sanctioned Chinese companies apart is the focus on goods. While banks account for most of the fines in Europe, Chinese companies are mostly fined for re-exporting US products. Like European companies, Chinese firms have opted to cooperate with the US authorities. Chinese banks have also been extremely cautious and scrupulous in following US sanctions laws. In particular, this could be felt by Russian companies in September 2018, when Moscow raised the issue of barriers faced by Russians when conducting transactions through Chinese banks. It can be argued that China is well aware of the threat of US fines against its banks and is not willing to take the risk even when dealing with companies that were not designated on any sanctions lists.

However, the US itself can change the way China deals with this matter. If Beijing gets a feeling that the US intentionally uses sanctions to contain the global ambitions of Chinese firms (especially in the high technology sector), the Chinese authorities will be compelled to retaliate. The situation could grow even worse if the political relations between Washington and Beijing deteriorate further, especially if the US goes full throttle on sanctions against China. Even though this turn of events appears to be unlikely for now, it cannot be ruled out for the future. In any case, China seems unlikely to offer a viable alternative to the US as the dominant power in global finance for many years to come.

Washington’s propensity to use its global financial dominance for political ends has long been a source of discontent beyond its borders. In today’s world, there are at least two major economic centres that are strong enough to create an alternative system of settlements so as to shield themselves from US sanctions. The European Union has the greatest potential in this regard: it has a developed economy, its own currency, and a global network of trade and economic ties. European companies get fined for violating US sanctions much more often than any other non-US entities and have to pay the highest penalties.

With the withdrawal of the US from the Iranian nuclear deal, the EU faces the urgent question of whether to take any protective measures. However, so far, Brussels has not been willing to create full-fledged global mechanisms that would shield it from sanctions. European companies tend to abide by US law and are unlikely to come together in demanding that the EU pursue a sovereign financial policy. From a business perspective, any shift in the global financial system is fraught with uncertainty, risk, and loss. For this reason, the European authorities are unlikely to face any substantial bottom–up pressure. There has been little incentive for the EU to undertake any serious initiatives at the political level as well. With the possible resumption of the Iranian nuclear programme, the question of whether European companies need an instrument for carrying out transactions with Iran becomes irrelevant, even more so since many major companies have already left Iran. In addition, the EU remains a US ally, and the EU’s overall sanctions policy is in tune with Washington’s policies, although there are some differences in terms of impact and reach. The EU is unlikely to create any frameworks or mechanisms to counter the United States.

Beijing also lacks any serious motives to create a global alternative. So far, the damage from secondary sanctions has been relatively limited. Chinese businesses are not eager to make a political issue out of the proceedings launched by US authorities. However, this does not mean that China will not be compelled to move in this direction in the future, especially if the competition between China and the US picks up momentum. Washington can go beyond the trade war by imposing sanctions to contain China’s technological development. In this case, China could take extensive measures in response. But nothing suggests that this scenario will actually materialize, at least in the next few years.

US dominance is thus cemented by the absence of any real contenders seeking to change the global financial system. While today’s world is multipolar in terms of military and political affairs, it remains unipolar as far as economic power and coercion are concerned. However, the US does not enjoy absolute power in this sphere either. Designated countries will always find ways to expand their ties with the outside world. It may seem like a paradox, but the integration of a targeted country in the global economy could further limit the impact of sanctions. Major economies like Russia that are an integral part of the global economy have the ability to adapt to sanctions even in the current environment. Even though the US retains a powerful arsenal for inflicting costs on the country it targets with sanctions and countries that violate them, it remains to be seen whether this power will yield political results and force targeted countries to change political course.

First published in the Valdai Discussion Club.

1. See: Hufbauer, G, Shott, J, Elliott K & Oegg, B, 2009, ‘Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Third Edition’, Washington DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, p. 3–5, 17.

2. See, for example, Drezner, D, 2015, ‘Targeted Sanctions in a World of Global Finance’, International Interactions, no. 41, p. 755-764; Tourinho, M, 2015, ‘Towards a World Police? The Implications of Individual Targeted Sanctions’, International Affairs, no. 91 (6), p. 1399-1412.

3. See: International Emergency Economic Powers Act. PL 95-223, 1977. Available from: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Documents/ieepa.pdf

4. SDN List Update of August 22, 2017, Office of Foreign Assets Control. Available from: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20170822.aspx; SDN List Update of August 15, 2018, Office of Foreign Assets Control. Available from: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20180815.aspx

5. The use of fines is regulated by a special instruction issued by the Department of the Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC). See: Economic Sanctions Enforcement Guidelines. Available from: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Documents/fr74_57593.pdf

6. For information about corporate and individual fines see: Civil Penalties and Enforcement Information, The US Department of the Treasury. Available from: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/CivPen/Pages/civpen-index2.aspx

7. Executive Order 13846 of August 6, 2018. Reimposing Certain Sanctions with Respect to Iran. Available from: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/08062018_iran_eo.pdf

8. After the Deal: A New Iran Strategy. Remarks of Mike Pompeo, Secretary of State. The Heritage Foundation, Washington DC, May 21, 2018. Available from: https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2018/05/282301.htm

9. Updating Blocking Statute in Support of Iran Nuclear Deal Enter into Force. August 6, 2018. Available from: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-4805_en.htm

10. Executive Order of May 8. Imposing Sanctions with Respect to the Iron, Steel, Aluminum, and Copper Sectors of Iran. Available from: https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/iran_eo_ metals.pdf

(votes: 4, rating: 4) |

(4 votes) |

The commonality of the political positions of the United States and the EU will ensure the status quo

Pressure on Huawei Will Spell Doom for American BusinessHuawei will probably try to resolve the issue with the U.S. authorities itself. The price will be very high, but, at the end of the day, Huawei is a business and not a state