Central Asia: Regional Development Trends

The 4446 m high Vladimir Putin Peak

is reflected in the porthole of a helicopter in

the Tian Shan mountains some 100 km

south of the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek

In

Login if you are already registered

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

Doctor of Political Science, Senior Researcher at the Analytical Centre of Institute of International Studies, MGIMO University

Post-Soviet Central Asia is one of the key regions for Russian interests in the areas of national security and economic development. The forthcoming pullout of the International Security Assistance Force in 2014 from neighboring Afghanistan makes the situation in that region critically important for international politics.

Post-Soviet Central Asia is one of the key regions for Russian interests in the areas of national security and economic development. The forthcoming pullout of the International Security Assistance Force in 2014 from neighboring Afghanistan makes the situation in that region critically important for international politics. Obviously, the long-term development forecast of the situation in the region has a rather significant practical value. However, analyses of various global [1] and regional [2] scenarios pay insufficient attention to long-term trends in the development of Central Asia. This article provides an analysis of regional development trends until the year 2030.

Demographic Explosion

Rapid population increases are typical for all countries in Central Asia (see Table 1). The countries of the region have a distinctively and relatively high birth rate, a significant vital index surplus and a low median age.

Kazakhstan is a partial exception with the highest characteristic median age of 29 years. Uzbekistan can also be cited among the exceptions with the lowest birth rate in the region, and respectively a lower natural population increaserate (a lower natality rate in Kyrgyzstan is mainly due to higher emigration). There is, however, a serious regional imbalance in Kazakhstan – a demographic explosion is being observed in some areas in the South with the most Islamized and least Russified population living there.

The above mentioned trends are most typical for Tajikistan, which has distinguished itself by the lowest median age, the highest birth rate and the highest population increase in the region.

Table 1 Central Asia by-country demographic profile *

| Country | Median age | Births per 1000 citizens (2012, estimate) | Deaths per 1000 citizens (2012, estimate)) | Population increase, % (2012, estimate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | 29.3 | 20.44 | 8.52 | 1.23 |

| Uzbekistan | 26.2 | 17.33 | 5.29 | 0.94 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 25.2 | 23.9 | 6.9 | 0.89 |

| Tajikistan | 22.9 | 25.93 | 6.49 | 1.82 |

| Turkmenistan | 25.8 | 19.55 | 6.21 | 1.14 |

* The Table isbased on data from the CIA Factbook.

Taking into account these trends, especially the low median age, it can be forecasted that population growth in the region will continue for at least another 20 – 40 years even if a gradual slowdown occurs. The point is that the age pattern of population will automatically reproduce a relatively high birth rate. Even after the end of population explosion, this region (especially Tajikistan and the Fergana Valley) will continue to be overpopulated with continuously scarce resources, primarily water, while living standards will not be as high as the rest of the world.

Migration

The incidence of a high population increase and overpopulation with relatively low living standards (see Table 2) will mean that the trend of active external migration in all directions will continue in the foreseeable future (for work or for education with opportunities to stay in the recipient countries).

Table 2 compares the countries of Central Asia with Russia as the main recipient of migration flows from the region. The data provided clearly show a division of the post-Soviet countries into two groups (see Table 2). Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan are characterized by a low per capita GDP, high unemployment rates and significant numbers of poor people. Moreover, taking into account the large number of young men living there, a high outflow rate of migrant workers becomes obvious – people who are ready to take any kind or even the hardest work. On the otherside, Russia and Kazakhstan accept these migrants. Besides, while the flow of migrant workers from Central Asia to Russia is high by absolute figures (Russia’s population is considerably larger than that of Kazakhstan), migrants’ inflow into Kazakhstan is higher by relative index (per 1000 population). Russia and Kazakhstan became migration recipient countries thanks to relatively high per capita GDP on a regional scale and a lower level of unemployment and poverty. Additionally, they have a higher average population age – Russia (38,8 yrs) and Kazakhstan (29,3 yrs) – and a larger share of female population in Russia due to high male mortality. All these factors naturally create great demand in Russia for males ready to accepthard and low paid jobs.

Turkmenistan represents a particular case. Thanks to rich hydrocarbon deposits, it has a relatively high per capita GDP relative to the region. However, high structural unemployment and poverty levels affect the intensity of migration outflow. This may haveto do with a specific structure of government created under Turkmenbaşy, that the new leader of the Republic Gurbanguly Berdymuhamedov has not yet been able to overcome through reforms (Let us recall that during the rule of Turkmenbaşy, when the government was spending enormous funds on prestigious projects, all hospitals outside the capital were closed down and the entire educational system according tovariousindicators was activelydismantled).

Table 2 Relationship between Migration Flows and Economic Factors in the Region and in Russia *

| Country | Migration increase/decrease per 1000 people. (2012, estimate) | Per capita GDP by purchasing power parity ($ US) | Unemployment % (estimate, official or unofficial) | Number of population below poverty line % (estimate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russia | 0.29 | 17,700 | 6.2 (2012) | 13.1 (2010) |

| Kazakhstan | 1.23 | 13,900 | 5.3 (2012) | 8.2 (2009) |

| Uzbekistan | -2.65 | 3,500 | 1 (2011, unofficial estimate – over 20) | 26 (2008) |

| Kyrgyzstan | -8.1 | 2,400 | 8.6 (2011) | 33.7 (2011) |

| Tajikistan | -1.21 (cyclical labor migration to Russia is insufficiently accounted for) | 2,200 | 2.2 (2009, official estimate; unofficial estimate – up to 50–60) | 46.7 (2009) |

| Туркменистан | -1.9 | 8,500 (2012, estimate) | 60 (2004, unofficial estimate) | 30 (2004) |

* The Table isbased on data from the CIA Factbook.

The abovementioned trends have been plagued byinertia and therefore will persist for another 10-20 years. Over the next several decades, Russia will probably remain the main destination of labor migrants from Central Asia (except Kazakhstan located in the same region). However, other migration vectors are emerging – for instance, towards oil producing Arab countries, Turkey and East Asia.

The shrinking of Russian speaking population and Russian culture in Central Asia and the regions of Russia

The demographic trends described above in terms of growth of the non-Slavic population and the departure of Russian speakers have already led to a situation where a large number of Russians, Russian speakers and Orthodox Christians have remained only in the two states of the “Eurasian” nomadic belt of Central Asia – Kazakhstan (in particular, in its northern part) and Kyrgyzstan (also mainly in the north).

Table 3 provides data on the number of Russians, Russian speakers and Orthodox Christians in the five states of Central Asia (It should be borne in mind that the numerical data given in this table are relative and notional since they are based on expert estimates, extrapolation from previous population censuses or the author’s own assessment).

Table 3 Number of Russians, Russian speakers and Orthodox Christians in the States of Central Asia *

| Country | Number of Russians (without accounting for other Slavic populations), % | Number of Russian speaking or bilingual population % (author’s or other experts estimate) | Number of Orthodox Christians (Russian Orthodox Church), % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | 23.7 (1999 census) | 95 (2001, expert assessment) | 44 (de-facto assessment includes almost all, who identify themselves as non-Muslim) |

| Uzbekistan | 5.5 (1996, estimate) | 14.2 | 9 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 12.5 (1999, estimate) | over 40–50 (ownassessment) | 20 |

| Tajikistan | 1.1 (2000 census) | 2–10 (ownassessment) | less than 1 |

| Turkmenistan | 4 (2003) | 12 | 9 |

* The Table isbased on data from the CIA Factbook.

There are no grounds whatsoever to assume that the described trends will not continue in the future for the same migration and demographic reasons. Moreover, as generations of elite raised in the USSR retire from power, these trends will acquire even greater proportions. Russians need to accustom themselves to the idea that perhaps in 20 – 40 years they will not be able to communicate in Russian with Central Asian elites. Since this tendency represents a serious challenge to the “soft power” potential of Russia in the region, it must be taken into account by Moscow. With all objective determinism of this trend, the Kremlin can substantially mitigate it through appropriate policies.

Nevertheless, the tendency toward the erosion of the “Russian World” will be evident not only in former Soviet Central Asia and Kazakhstan but also in Russia itself - up to the establishment of large enclaves populated by Central Asian expatriates. In 2012, stabilization occurred and even with a slight increase of population of Russia was observed due to migration. However, most of the experts believe that the tendency of Russian population to decrease, especially among the native population,is irreversible. At present Russia ranks second in the world after the USA according to the number of immigrants. Moreover, Central Asia makes an increasingly significant contribution to this migration.

Theoretically, this situation may evolve in such a way that after 2050,migrants from Muslim countries and natives of the Muslim regions of Russia will constitute a majority in the European part of Russia. Furthermore, this situation will not be unique: quite recently representatives of ethnic and racial minorities in the U.S. reached a majority among the children born. Meanwhile, the problem has to do with the ability of the government to adapt to the new circumstances through effective integration of migrants or representatives of national minorities or partial “relief” of demographic problems in the migrants’ recipient society.

Russia has considerable potential to make the demographic problems less acute, albeit not necessarily through increasing the birth rate as it is commonly believed. Indeed, such measures as “maternity capital allowance” encouragean increase in natality among naturalized migrants and representatives of some ethnic minorities (e.g. Muslim peoples of the North Caucasus) perhaps even higher than among local populations. Even worse, these measures encourage higher birth rates predominantly among the marginal strata of Central Russia’s native population (i.e. chronic alcoholics), which is fraught with no lesser problems than uncontrolled migration. Another very important resource for demographic stabilization is the reduction of still high mortality rate, especially among the male population (It should be noted that unlike anywhere else in the world, Russia has an unprecedented gap between the life expectancy of men and women, while men quite often die at their most productive age). The overall demographic stabilization and effective integration of migrants and representatives of ethnic minorities, especially Muslim minorities, into the host society are a part of the problem related to developing a more productive model of social and economic development of Russia.

Raw-material-based economies of the region, tendency of “de-modernization”

The “raw material dependency” is much more typical for the economies of Central Asia than for Russia. This is the dependency on gas for Turkmenistan, oil and nonferrous metals -- for Kazakhstan and gas and cotton – for Uzbekistan. Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are today in the most difficult situation – they cannot fully utilize their existing richhy dropower resources. It is very unlikely that overthe next few decades, the situation will radically change. Moreover, a tendency of “de-modernization” is being observed.For example, in 2010 the percentage of urban residents in Tajikistan dropped to 26% of the total population due to civil war and economic hardships, -- a level comparable to the most backward countries of the world. The departure of highly-skilled professionals and intellectuals (both Russian-speaking and national), and the disintegration of technical and social infrastructure that was created in Soviet times even in such countries rich in mineral resources as Turkmenistan, can also be considered manifestations of “de-modernization”.

All of this will lead in the future to a continuation of persistently low living standards in the region. There are some prospects of achieving higher relative living standard in Kazakhstan. The republic possesses rich natural resources and a relativelyliberal and efficient (for the post-Soviet region) economic model. Turkmenistan has much fewerchances to improve its living standards as a country that possesses rich natural resources but anextremelyinefficient system of governance.

Sultanistic and neopatrimonialregimes: Clan patterns insociety

For all the countries of the region (politically unstable Kyrgyzstan might be considered a partial exception), regimes of personalized authoritarian power are typical; they are often referred to as “Sultanistic” by academics (a term introduced by J. Linz) [3]. Their socio-political systems are generally called “neo-patrimonial” [4]. The latter are characterized by an indivisibility of power and property and anarchaization of political systems, in particular, through the incorporation of clan-tribal structures.

Clan-tribal structures proved their vitality over 70 years of Soviet rule, survived periods of active suppression (e.g. the Andropov-Gorbachev “cotton campaign” in Uzbekistan) and experienced a renaissance overthe last 20 years [5]. Taking this into account, it can be forecasted that they will be preserved in this or another form for at least the next half century.

“Fragility” of States, Instability and Security Risks

All countries in the region are characterized by rather high risks, primarily in terms of new security threats, especially terrorism and Islamic extremism. The escalation of these threats is associated with nearby Afghanistan. The statehood of a number of Central Asian countries is also coming under threat. According to the 2011 failed states index made by the Fund for Peace, Kyrgyzstan (91.8 points) is the most “fragile” among all post-Soviet state. It can be forecasted that the high degree of such threats will persist overthe next 30 years.

Outside interference and prevalence of centrifugal tendencies

The weakness of the Central Asian states and the important geopolitical role of the region entails a high degree of Great Power involvement in their regional affairs and constitutes the substance of the “New GreatGame”. Meanwhile, Central Asian States themselves are not showing any particular desire for consolidation, which is evidenced by the failure of regional integration projects. Neither Kazakhstan (the biggest country of the region in terms of territory and the size of economy), nor Uzbekistan (the biggest country in terms of population and military power) have been able yet to play the role of efficient integration centers or successfully counter quite sustainable centrifugal tendencies.

* * *

The above-described tendencies allow us to envision the situation in the region for the next 30 years with a rather high degree of confidence. Such a projection of existing trends is normally called an “inertial scenario”.

According to this scenario, demographic growth in Central Asia will continue, albeit gradually slow down. Due to overpopulation of fertile areas in the region and a deficit of resources, rather low (by world rating) living standards will persist. Migration, primarily to Russia, will continue. A reduction in the size of the Russian speaking diaspora and a reduction of the role of Russian language both in Central Asia and some adjacent areas of the Russian Federation will take place unless systemic measures are taken to counter this trend. The economies of the region will continue to be based on raw materials with a tendency towards “de-modernization” conditioned by the persistence of traditional clan structures and preservation of personalistic, neo-patrimonial regimes. All this will contribute to political instability and the growth of non traditional threats, both in Central Asia and contiguous countries (primarily Russia and China). Players outside the region will continue to interfere in regional affairs and the level of interaction among the countries of Central Asia will remain low. The overall situation in the region for the next 30 years does not seem either quite optimistic or catastrophic if the “inertial scenario” were to be implemented.

A large number of various factors described above can engender as well numerous alternative options for the future in case of a deviation from the “inertial scenario”. The regional situation in this context is characterized by a high degree of uncertainty. It should be noted that the respective scenarios can be drawn for each of the “bifurcations” of potential future listed below.

The demographic and migration situation may vary within a rather wide range. A catastrophic scenario of continued unchecked demographic growth may take place in the poorest countries of the region, which is fraught not only with an acceleration of uncontrolled migration but also social unrest, especially in Tajikistan. However, we should not either that the demographic situation will relatively stabilize with a more rapid reduction of population increase, especially if the countries of the region, alongside outside financial support, engage in an active demographic policies.

The destiny of the “Russian World” will much depend on the efforts of Moscow to promote Russian language and culture abroad (there are some positive tendencies in this respect, related first of all to the activity of Rossotrudnichestvo– the Russian International Cooperation Agency), as well as the policy of the Russian Government in the area of migrant integration.

The social and economic development of the region will be mainly determined by the behavior of raw material prices on foreign markets. It should not be dismissed either that Central Asian Governments have a certain degree of discretion in setting the “rules of the game” that they can use in their interests.The comparison of two countries of the region rich in premium market hydrocarbon resources – Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan – shows that these resources can be disposed of differently.

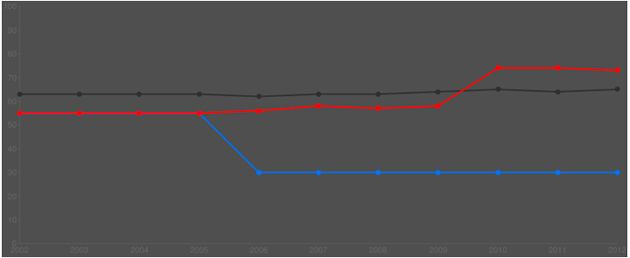

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the degree of economic freedom in Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan in 2002-2012 as compared to average world indicators according to the annual rating compiled by the “Heritage Foundation” and the “Wall Street Journal”. In 2005, when the situation in the two countries was almost similar, Kazakhstan managed to make a spurt and reached alevel of economic freedom above the world average. Turkmenistan, on the contrary fell to a very low level.

Figure 1 Freedom of business in Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan compared to average world indicators

Source: Heritage Foundation.

Black line – World average

Red line – Kazakhstan

Blue line –Turkmenistan

Vertical axis – Degree of economic freedom

Horizontal axis – Years

Since the social and political systems of the countriesin the region are rooted in their clan social structures, they will most likely preserve their current patterns. However, some variations are possible in this context. Thus, the political systems of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan may become more authoritarian while those of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan will become more liberal (a limited liberalization has been already observed in Turkmenistan after the passing of Turkmenbasy).

State stability and security risksare two problematic aspects. The recognition of one or two states as “failed” (obvious candidates are Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) will radically aggravate the situation in the region. Developments in Afghanistan after 2014 may set off an unpredictable scenario, which naturally will affect its neighbors.

Outside interference creates the most complex and ramified possibilities in regional developmentup to the year 2030. Let us single out the most important of them in view of their potential impact. There is a probability of either stronger cooperation among the Great Powers involved in the region’s affairs on issues of maintaining regional stability or their rivalry, including pertaining to ideology (especially, between the West on the one hand, and Russia and China, on the other). It is quite possible that the influence of China will grow further, perhaps even reaching qualitatively new levels (so far it has been achieved by means of economic and “soft” power). Eurasian integration may also significantly contribute to achangein the regional situation.

By and large, the analysis of alternative options for the future demonstrates an extremely high vulnerability forthe Central Asian region and a high degree of policymakers’ responsibility, including those in Russia, for further developments. The state of affairs in Central Asia is difficult but not hopeless. The high level of uncertainty by itself suggests that targeted policymakers’ actions both in the countries of the region and in a number of Great Powers can make the future along the southern borders of Russia either catastrophic or almost acceptable.

1. National Intelligence Council of USA, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, December 2012 (http://www.dni.gov/nic/globaltrends); European Strategy and Policy Analysis System Report «Global Trends 2030 – Citizens in an Interconnected and Polycentric World». Paris, Institute for Security Studies European Union, 27 April 2012; Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO). Strategic Global Outlook: 2030. Short Version (in English) / Ed. by A.A. Dynkin. M.: IMEMO RAN, 2011; World Economic Forum. Risk Report 2011 (http://riskreport.weforum.org/).

2. Russia in 2020: Scenarios for the Future / Edited by M. Lipman, N. Petrova, M.: ROSSPEN, 2012; A.A.Kazantsev Scenario Analysis of Situation Development in the Central Asian Region: potential consequences for the interests of Russia and CSTO //IIS-2012 Yearbook. MGIMO -- University, 2012. P. 332-350; Borishpolets K.P., Chernyavsky S.I. Scenarios for Situation Development in the Region of Central Asia // IIS-2010 Yearbook. M.: MGIMO – University, 2011. P. 301-309.

3. Sultanistic Regimes / Ed. by H.E. Chehabi, J.J. Linz. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1998.

4. Eisenstadt S.N. Revolution and the Transformation of Societies:a Comparative Study of Civilisations. M.: Aspect Press, 1999. P.324-359.

5. Collins K. Clan Politics and Regime Transition in Central Asia. N.Y.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |