The attack on the infrastructure facilities of Saudi Arabia’s national oil and gas company Saudi Aramco is the largest interruption of energy supplies in history (in absolute terms). Over half of Saudi Arabia’s facilities (with a total capacity of 5.7 million barrels per day) were knocked out of service, as the strikes hit the Khurais oil field (with a capacity of 1.5 million barrels per day) and the oil-processing facilities in the town of Abqaiq that the media often mislabel an oil refinery. The losses total 5 percent of the global oil production, an unprecedented phenomenon for the 21st century, although the physical damage is nothing compared to the damage this incident will do to reputation of the global energy community.

After the “Black Monday” of September 16, 2019, Dated Brent prices temporarily soared above USD 70, but the market had calmed down by the end of the week and oil prices rolled back to USD 62–63 per barrel. Nonetheless, market participants were still anxious about escalating tensions in the Middle East, for if the proxy clashes that have thus far characterized the confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran transform into a direct, “hot” conflict, then such a development promises significantly worse consequences than one-off price fluctuations. Riyadh and Tehran fear a direct conflict. However, the potential for further provocations, whether in the Strait of Hormuz, Bab-el-Mandeb or in other places, is still significant.

The attack on the infrastructure facilities of Saudi Arabia’s national oil and gas company Saudi Aramco is the largest interruption of energy supplies in history (in absolute terms). Over half of Saudi Arabia’s facilities (with a total capacity of 5.7 million barrels per day) were knocked out of service, as the strikes hit the Khurais oil field (with a capacity of 1.5 million barrels per day) and the oil-processing facilities in the town of Abqaiq that the media often mislabel an oil refinery. The losses total 5 percent of the global oil production, an unprecedented phenomenon for the 21st century, although the physical damage is nothing compared to the damage this incident will do to reputation of the global energy community.

It should be noted that Abqaiq is probably the most important point on the oil industry map. No other place on Earth has such a concentration of oil flows. Some of the oil from the world’s largest oil field (Ghawar) is also processed at Abqaiq. The vulnerability of Saudi Arabia’s oil industry has been a topic of discussion for some time now, and several attacks on Abqaiq have either been carried out or planned over the past several years. For example, in 2006, Al-Qaeda militants attacked Abqaiq intending to seize it, but the Saudi military was able to repel that attack.

The strikes against Abqaiq indicate that the perpetrators were extremely well prepared since the facility serves as a kind of collective hub for surrounding oil fields, where the facilities are used to desulfurize the oil and to separate the oil gas. These are the facilities that were hit at 4 a.m. on September 14. Nominally, therefore, Riyadh lost only one-seventh of its oil production, but the damage caused to the facilities in Abqaiq meant that Saudi Arabia was unable to deliver Arab Light and Arab Super Light grade oil to the market since their full production cycle takes place in at the Abqaiq facilities.

The loss of over half of Saudi Arabia’s oil production, if only for a time, will primarily hit Asian countries, which account for about 80 percent of Saudi Aramco’s exports. These countries can make up for the shortage in three ways. First, they can use their own strategic reserves (China’s reserves alone are estimated at about 700 million barrels, however, there is no historic precedent for such steps); second, they can switch to other oil grades, that is, in the absence of Arab Light and Arab Super Light they can import heavier/lighter grades of oil, including Arab Medium and Arab Heavy; finally, they can increase shipments from Iran either directly, or by producing new mixes, similar to what happened in the coastal waters of Malaysia in July–August 2019.

Price Shake-Ups

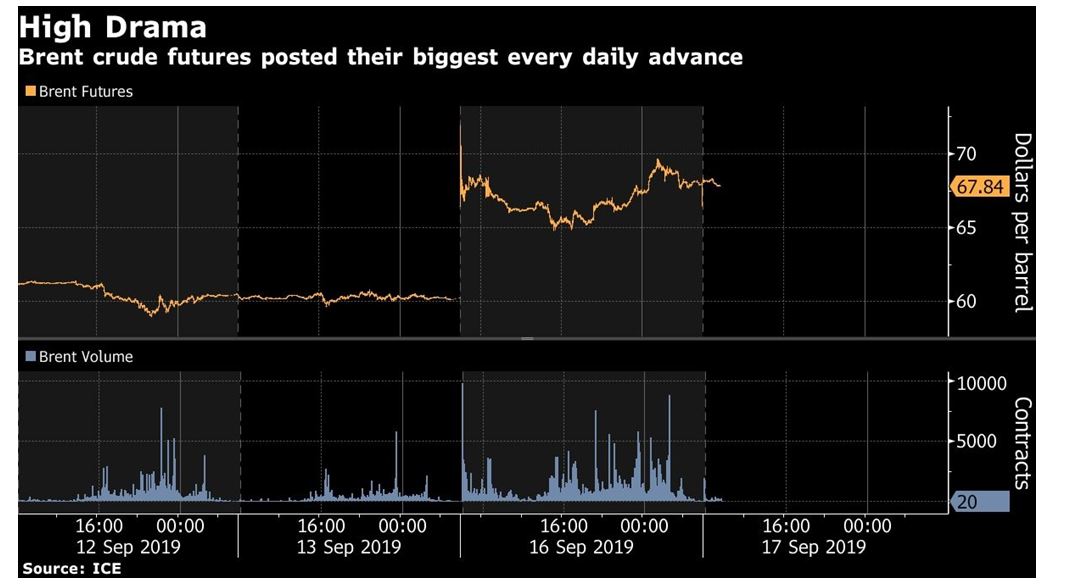

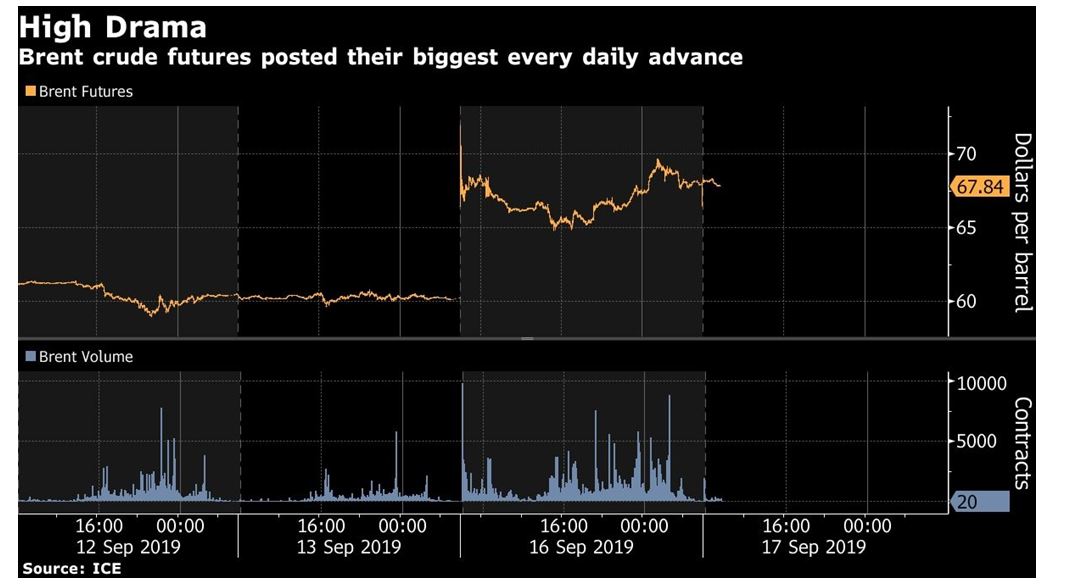

The markets initially reacted with borderline panic: over a single day, Brent, the global benchmark, went up USD 8.8 per barrel (WTI increased by USD 8 per barrel). The last time such a jump was recorded in September 2008, when the market seesawed on the eve of the global financial crisis. Following a series of statements from Saudi Aramco promising that Saudi Arabia would fulfill all of its contractual obligations due to its sufficient oil reserves and that by late September 2019 most facilities would be up and running again, oil prices began to go down.

Figure 1. Brent Prices September 12–17, 2019

Source: Bloomberg

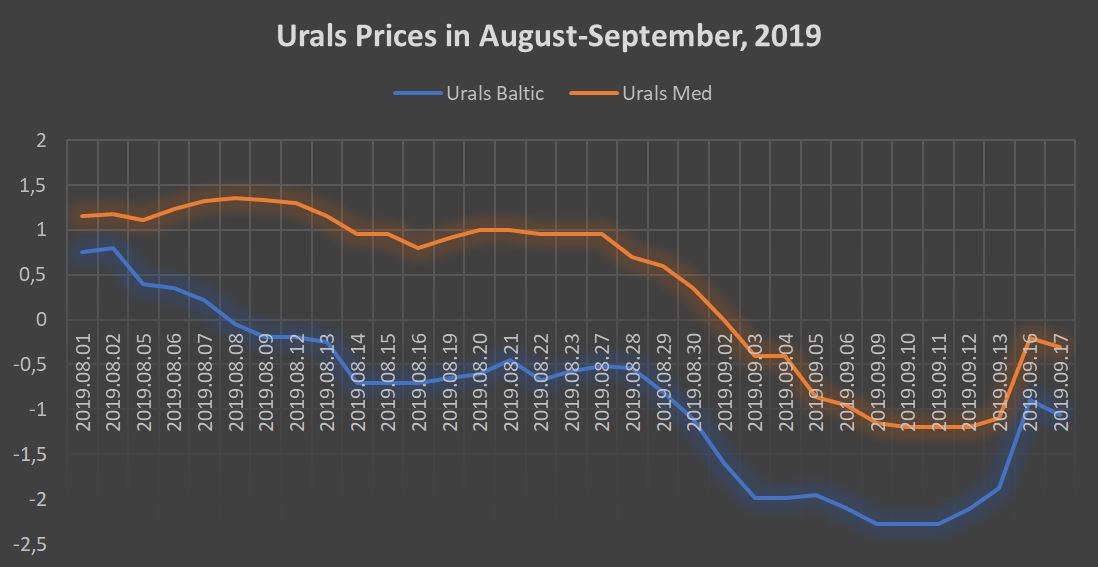

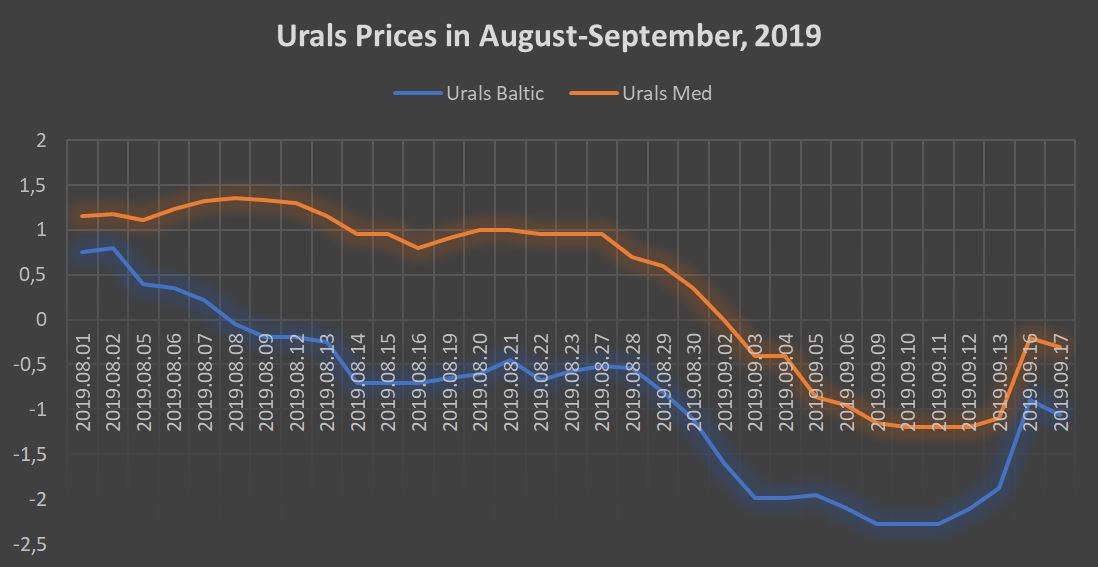

Notably, market panic was a positive thing for Russia. Prices on Urals, Russia’s principal exported grade of oil, went up USD 1 per barrel and thus ended the creeping (and somewhat inevitable due to new IMO 2020 regulations that will soon come into effect) depreciation of the last two to three weeks. The virtual shutdown of production of Arab Light grade oil mostly benefited those producers whose oil is similar in quality.

Figure 2. Urals Prices in August–September, 2019

Source: S&P Platts

Russia’s ESPO oil grade is a sweet crude analog of Arab Light (ESPO has an API gravity of 35°, while Arab Light has an API gravity of 34°). Following the events in Saudi Arabia, ESPO prices exceeded the record from six years ago, when Surgutneftegas oil and gas company sold four cargoes of oil at a premium of USD 7.2 a barrel against the Middle Eastern Dubai benchmark. It should be noted that, on the whole, any interruptions in supplies of sour oil grades (heavy and medium gravity) will inevitably benefit Russia, since the OPEC+ agreements curtails production of these particular grades and this quality segment accounts for the larger part of Russia’s exports.

According to S&P Global Platts, global spare oil capacity totals 2.3 million barrels per day; however, 1.6 million barrels of these are in Saudi Arabia. Thus, if military hostilities or domestic conflicts render Saudi Arabia incapable of controlling its oil production level, no one will be able to replace Riyadh on the global oil market. Given the strategic purpose of complying with the OPEC+ agreement, Russia’s spare capacity today is 0.2–0.3 million barrels a day. Russian producers could use these capacities. However, this requires all OPEC/OPEC+ participants to take a joint stance on the issue.

Estimates vary as to Saudi Arabia’s prospects of restoring the damaged facilities and reaching the level of oil exports it had prior to September 14, 2019. However, most analysts tend to believe that full recovery will take months, and in the meantime, OPEC member states should think about filling the market niche. Paradoxically, the only country capable of supplying the required volumes of oil is Iran, whose production has fallen by approximately 2 million barrel per day due to U.S. sanctions.

Tehran denies its involvement in the attack, although the U.S. and Saudi secret services claim the Iranian forces took a direct part in the operation. It should be noted that the Houthi military coalition Ansar Allah claimed responsibility for the attack, but the strikes were delivered with such precision that it prompts additional questions. Serious intelligence information is required in order to know that the low-flying objects might be missed by the missile defense systems around Abqaiq, especially since Abqaiq was hit from the west, and that required knowledge of the fact that Saudi missile defense systems were covering the northeast (towards Iran and Iraq) and the south (Yemen), leaving the western direction, the “no man’s land,” open.

What about the United States?

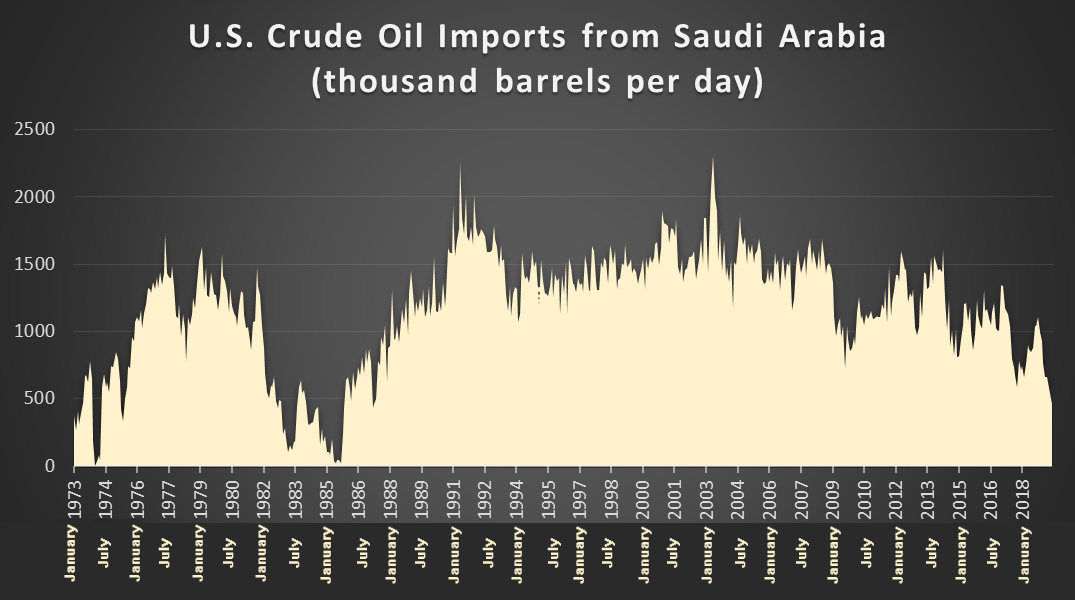

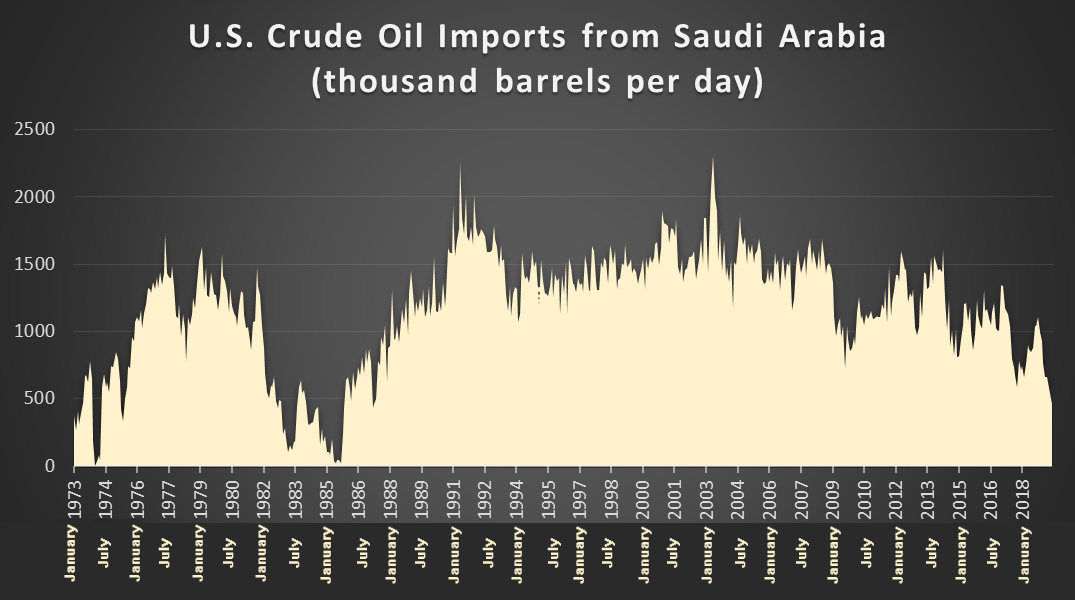

The shale revolution in the United States made the country the world’s largest oil producer, yet it simultaneously weakened its strategic ties with its Middle Eastern partners. While military cooperation between the United States and Saudi Arabia remains high (despite the fact that imports from Saudi Arabia are at a 32-year low, see Figure 2), American voters will henceforth be more reserved in their opinions on any actions the White House might take in the Middle East. The Trump administration understands this very well, and despite its highly aggressive foreign political course against Iran, it has currently acted in a very reserved manner.

Figure 3. U.S. Crude Oil Imports from Saudi Arabia (thousand barrels per day).

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

|

We don’t need Middle Eastern Oil & Gas, & in fact have very few tankers there, but will help our Allies!

|

Donald Trump’s tweet of September 16, 2019

|

The reaction of the United States regarding its own energy policy was reserved as well. Although Donald Trump authorized the release of U.S. strategic reserves on the first day of the market panic, as the situation stabilized, he stated that the prices had not grown much and an increase of USD 5 per barrel is not a problem for the United States. Therefore, the question of using the strategic reserves of the United States vanished from the agenda rather quickly. Stating that the immediate priority of the United States is to link as many pipelines as possible to the ports in the Gulf of Mexico, Trump hinted that his administration intends to reduce oil prices (and, consequently, bring down politically sensitive gas prices in the United States) by increasing U.S. exports.

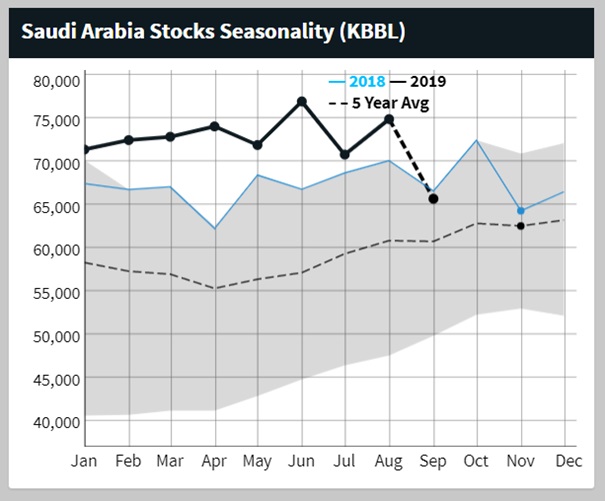

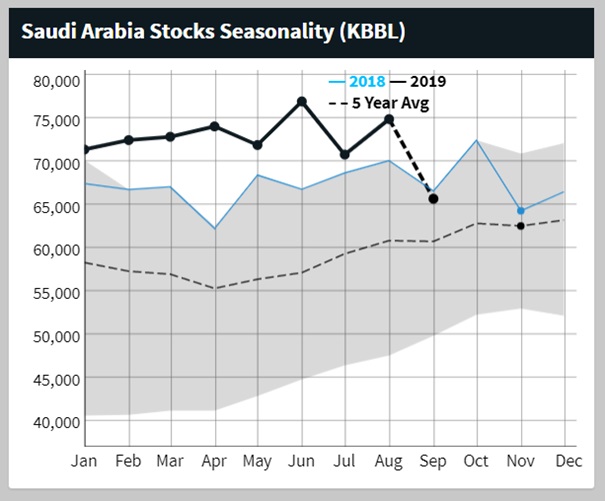

Figure 4. Saudi Arabia’s Oil Reserves, thousand barrels

Source: OilX

So, what can Saudi Arabia do? First, Saudi Aramco will attempt to restore the damaged facilities in Abqaiq as fast as possible and bring them back to operating at their design capacity. In the meantime, Saudi Arabia will use its oil reserves. However, that will not solve protracted problems. As of late August (see Figure 3), Saudi Arabia had about 75 million barrels of oil in reserve, which would cover about ten days’ worth of exports. We should add to this approximately 30 million barrels owned by Saudi Aramco and stored in the ports of Sidi Kerir (Egypt), Okinawa (Japan) and Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

Second, the attack on Abqaiq amply proves the need for diversification in Saudi Arabia. Its national oil and gas company, Saudi Aramco, will need to step up production at the facilities that are not linked with the East-West Crude Oil Pipeline, primarily at the shelf oil fields in the Gulf of Persia. A protracted dispute with Kuwait concerning the use of the so-called Neutral Zone begs to be settled since such major fields as Wafra and Khafji could add 0.5 million barrels a day in mere months.

Comparing the Houthi strike against Saudi Arabia with Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait is not accidental; ever since 1990, there has been no sharper price jump and no greater physical damage to oil facilities. However, unlike the full-scale military operation back then, this operation involved drones carrying cruise missiles, which did not require the attackers to be physically present at the territory under attack. Repeat attacks and growing tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran put a question mark over the future of Middle Eastern exports, of those 14–15 million barrels a day that pass through the Strait of Hormuz. The sudden desire of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirate’s to join the U.S.-led International Maritime Security Structure (IMSC) stems from their inability to protect their oil assets fully.

After the “Black Monday” of September 16, 2019, Dated Brent prices temporarily soared above USD 70, but the market had calmed down by the end of the week, and oil prices rolled back to USD 62–63 per barrel. Nonetheless, market participants were still anxious about escalating tensions in the Middle East, for if the proxy clashes that have thus far characterized the confrontation between Saudi Arabia and Iran transform into a direct, “hot” conflict, then such a development promises significantly worse consequences than one-off price fluctuations. Riyadh and Tehran fear a direct conflict. However, the potential for further provocations, whether in the Strait of Hormuz, Bab-el-Mandeb or in other places, is still significant.