The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: What, Where, When, Why and How Much

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |

PhD in History, Professor at Chair of Theory and History of International Relations, Boris Yeltsin Urals Federal University

Established by more than 50 nations in 2015 and officially opened for business in January 2016, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has become a new international financial institution, one of the People’s Republic of China’s largest international projects and a new format for that country’s interaction with the world at large. Will AIIB be able to outgrow the role of a financial tool of Chinese diplomacy?

Established by more than 50 nations in 2015 and officially opened for business in January 2016, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has become a new international financial institution, one of the People’s Republic of China’s largest international projects and a new format for that country’s interaction with the world at large.

The cast and crew

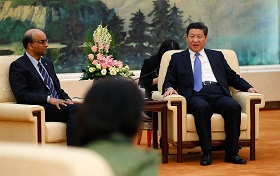

The Chinese leadership first had the idea of the new institution a few years back and China’s President Xi Jinping announced it publicly in October 2013. A year later, representatives from 21 countries signed a Memorandum of Understanding in Beijing to establish AIIB. The AIIB Articles of Agreement were signed on June 29, 2015 in Beijing. Its founding members included 57 countries spanning the world from Western Europe to Australia. The biggest founding members by the amount of contributions to its authorized capital were China, India, Russia, Germany and South Korea. The Articles entered into force when legislatures of ten signatories with initial capital subscriptions totaling at least 50% of the allocated shares ratified them. At a solemn ceremony Beijing on January 16, 2016 attended by China’s President Xi Jinping and delegations of member nations an official announcement was made of the start of the bank’s operations.

What’s on paper

According to the Articles, the purpose of AIIB is to foster sustainable economic development, create wealth and improve infrastructure connectivity in Asia and promote regional cooperation in close collaboration with other multilateral and bilateral development institutions [1]. Active promotion of public and private investment is envisaged [2]. Membership is open, yet a proportion of Asian to non-Asian members established in the Articles should be maintained. In no event may the percentage of capital stock held by “regional members” fall below 75% of the total subscribed capital stock [3]. There is a path to membership for “applicants which are not sovereign or not responsible for the conduct of their international relations” [4].

Although the US dollar is named as the Bank’s official currency [5], many Articles mention the possibility of using other currencies too. A member considered as a less developed country may pay its subscription in installments and in the currency of the member, provided however that whenever the foreign exchange value of a member’s currency has depreciated, that member should pay to the Bank “within a reasonable time” an additional amount to cove the difference [6].

The “Bank’s resources” include not only authorized capital stock and funds raised through various operations, but also “funds received in repayment of loans or guarantees” and “any other funds or income received by the Bank which do not form part of its Special Funds resources referred to in Article 17 of this Agreement” [7]. This is a broad enough provision that gives ample leeway to whoever happens to be at the helm of the Bank or any of its projects.

Yaroslav Lissovolik:

Is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

a New Bretton Woods?

The Bank “may provide financing to any member, or any enterprise operating in the territory of a member, as well as to international or regional agencies or entities concerned with economic development of the region”, but in “special circumstances and by a Super Majority vote of the Board of Governors” [8]. No explanation of the “special circumstances” is given in the document. The total outstanding amount of financing provided by the Bank cannot exceed the amount of its ordinary resources, yet the Board of Governors may increase the limitation by up to 250% [9]. The Bank shall be guided by “sound” banking principles in its operations [10], something that – in a reflection of the document’s Chinese authorship – has an emotional and judgmental rather that strictly legal sound to it. The term’s synonyms can include such words as “sustainable”, “quality”, “healthy”, “reasonable” or “robust”. The environmental and social impacts are not emphasized but only mentioned in passing [11]. Paragraph 11 of Article 13 is of particular interest: “In its equity investments, the Bank shall not assume responsibility for managing any entity or enterprise in which it has an investment and shall not seek a controlling interest in the entity or enterprise concerned, except where necessary to safeguard the investment of the Bank”.

Even when AIIB was still being established, the West came to the conclusion that this project would only serve China’s interests.

The Bank may establish such rules as may be necessary, consistent with the provisions of the Agreement [12]. The Board of Governors – the Bank’s main representative body – determines what part of the net income of the Bank shall be allocated and in what currency [13]. This means that income may be disbursed in yuan rather than US dollars, and member states will have to decide what to do with it. The Board of Governors may obtain a vote of the Governors on a specific question without a meeting – which is rather unorthodox – and provide for electronic meetings of the Board of Governors in special circumstances [14]. Each member is represented on the Board of Governors, but Asian countries dominate on the Board of Directors at a ratio of three to one [15]. A Director is entitled to cast the votes of more than one member [16]. The principal office of the Bank is located in Beijing [17], while any other offices can only be supplemental. Still, the working language of the Bank is English [18].

Finally, there is a procedure for withdrawal of membership, but it must be on a six months’ notice and a withdrawing member shall remain liable for all direct and contingent obligations to the Bank to which it was subject at the date of delivery of the withdrawal notice; the Bank also must arrange for the repurchase of such country’s shares [19]. Article 46 grants the Bank “immunity” from every form of “legal process, except in cases arising out of or in connection with the exercise of its powers”, and property and assets of the Bank are immune from all forms of seizure, attachment or execution before the delivery of final judgment against the Bank. Similar articles apply to the Bank’s officers and employees and to exemptions from taxes and customs duties.

The Articles are thus very detailed and cover every aspect of the Bank’s operations, and yet they contain some vague language that can be interpreted in different ways.

Many actors, and many points of view

The AIIB’s Launch Sets the Stage for Supply-

Side Competition in Development Finance

The scope of AIIB’s activities is somewhat restricted by the existence of large global and regional actors, such as the IMF, the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, and the OECD. The United States and Japan have met the emergence of the new institution with the strongest skepticism because of its perceived threat to their interest in Asia. Both nations, which are among the key members of the above financial institutions, officially announced their opposition to joining AIIB. Western analysts were quick to speculate about whether the new player would provoke a new round of intense global competition. It has been noted that it was hard to explain why the already existing World Bank or the Asian Development Bank could not be used to facilitate the development of Asian countries. Besides, even when AIIB was still being established, the West came to the conclusion that this project would only serve China’s interests.

Japan went even further as it branded AIIB “a domestic bank of China”. There are some doubts over whether it can even be considered a truly international institution given the existing proportions that countries hold in its authorized capital and in its voting structure. Not entirely unreasonably, it has been claimed that it makes no sense for an international bank to have its principle office in Beijing and a Chinese citizen as its Chairman. At the same time, some in the business community have questioned the wisdom of staying away from the new institution. Japan’s economic losses caused by the emergence of AIIB are above all linked to a strengthening of China’s cooperation with the Silk Road Economic Belt nations and the notion that this is exactly the purpose of AIIB, which could jeopardize Japan’s interests in the region.

Observers have also raised certain questions about the Bank’s project management practices: How will it be meeting environmental and legal standards? It has also been noted that the United States was unable to prevent the establishment of a powerful regional rival: Many of its allies actually joined AIIB, and the new institution could tip the balance of power in Asia-Pacific and even threaten the US- and Japan-led Trans-Pacific Partnership. The United States was most incensed over the accession to AIIB of the UK, South Korea and Australia.

Some analysts are also concerned that the United States chose a wrong strategy vis-a-vis the new institution to begin with, and that by distancing itself from AIIB it could suffer economic, political and “image” damages.

Yet there are alternative points of view as well, such as that it could be possible for the United States to do its best to “turn AIIB into a positive player in global processes” in “coordination of efforts with Japan and other allies” or the need to more actively develop the already existing institutions controlled by the United States. There is a notion that the outlook for AIIB is uncertain because of potential disagreements between China and the Bank’s Western co-founders on environmental and anti-corruption standards and non-interference in internal affairs. Some analysts are also concerned that the United States chose a wrong strategy vis-a-vis the new institution to begin with, and that by distancing itself from AIIB it could suffer economic, political and “image” damages.

As far as the Republic of Korea – a US ally in Asia-Pacific that joined AIIB unexpectedly – is concerned, that country’s largest news agency Yonhap reported citing a government source that partnership with the new organization would be “strengthening”, while representatives of South Korea’s largest business entities actually called for increasing cooperation with China, primarily because the Chinese market is among the largest for South Korean exports.

Representatives of South Korea’s largest business entities actually called for increasing cooperation with China, primarily because the Chinese market is among the largest for South Korean exports.

Russia’s position on the new institution’s prospects has not yet been articulated very clearly. Yet Russian President Vladimir Putin has expressed hope that the activity of AIIB, as well as that of the BRICS New Development Bank, established earlier, “would not only promote development in Asia-Pacific, but would also contribute to the strengthening of the global financial system’s stability”. The size of Russia’s equity contribution to the Bank is a measure of seriousness of its expectations of AIIB [20]. However, whether some of those expectations are well founded is open to doubt. For instance, Deputy Minister of Economic Development of the Russian Federation Stanislav Voskresensky has said that the Bank would operate under “principles similar to those of the EBRR”, while financing of its first projects could come through in 2016. It’s hard to assume that an organization, dominated for all intents and purposes by China, as discussed above, would act according to classic Western rules of doing business. As far as the start of project financing is concerned, this would only be possible once the Articles of Agreement come into force and the Bank, which still looks more like a virtual entity, completes its financial institutionalization. Meanwhile, Russian companies are already making plans for receiving Chinese investments through AIIB without giving much thought to specific terms and conditions or timelines.

The attitude of the existing international financial institutions towards the Bank has proved to be more flexible than positions of individual countries. The IMF has expressed readiness to cooperate with AIIB as IMF chief Christine Lagarde said the IMF would be “delighted” to co-operate with AIIB and the institutions have “massive” room for cooperation. World Bank President Jim Yong Kim had expressed a similar point of view earlier.

The Japanese President of the Asian Development Bank Takehiko Nakao said in a report to the 48th annual meeting of its Board of Directors that “given the increased demand for credit, the establishment of a new financial institution is a natural process”, and that the ADB “understands and welcomes this”; at the same time (perhaps to preempt future competition from AIIB), he announced an increase in lending to Asian countries. And Angel Gurria, Secretary-General of the OECD, during a visit by a Chinese delegation to Paris “offered OECD’s experience” and called it a “welcome partnership, as the OECD works closely with many Asian countries”.

A bank with Chinese characteristics

In light of the above, we believe that it is important to understand the actual scope of China’s involvement and Beijing’s role in AIIB. The first thing that stands out is that it was China’s Ministry of Finance that came up with the idea of AIIB. China’s former Deputy Minister of Finance Jin Liqun was acting President of the Bank during the preparation period before being officially appointed to the post. China’s Ministry of Finance also served as an official liaison with AIIB during its formation. Its principal office is located in Beijing in a departure from earlier plans to deploy it in Hong Kong. China is the leading contributor by volume: According to some data, they have contributed $50 billion. The voting quotas have allocated according to contribution amounts. At the same time, Beijing imposed a $100 billion cap on the total amount of authorized capital to begin with so that other countries could only make smaller contributions and thus receive a smaller share of the votes. The Articles describe the Government of the People’s Republic of China as Trustee for the Bank [21].

The very specialization of the Bank satisfies China’s aspirations at this point of time. A comparative analysis of multiple Chinese investment projects in Russia, Central Asia, Latin America and Africa demonstrates that in almost all cases the construction of infrastructure is a priority for China’s capital exports. China’s benefits are three-fold: Domestic jobs creation, more orders for Chinese companies, and payment by recipient countries for Chinese goods and services with proceeds from its own loans. It is no coincidence then that analysts have been comparing the project of resurrection of the Great Silk Road to the Marshall Plan, even though China has carefully avoided any such association. Established to facilitate this project to begin with, AIIB simply helps expand the basis for China’s investment cooperation with the rest of the world. According to China’s Minister of Commerce Gao Hucheng, AIIB’s resources will be used for the development of cooperation among the SCO member countries.

It’s hard to assume that an organization, dominated for all intents and purposes by China, as discussed above, would act according to classic Western rules of doing business.

Interestingly, in order not to damage relations with the Western-controlled global financial institutions, China has made simultaneous announcements of expanded cooperation with the IMF and the World Bank and the establishment of a $50 million fund to combat world poverty jointly with the latter.

The Chinese media have been making the following pitch in connection with the establishment of AIIB: The world has three power poles – China, the United States and Europe, and three leading currencies – the US dollar, the euro and the yuan. The need for “internationalization” of the yuan given China’s economic growth and crisis phenomena in the US economy is apparent, and the new institution will facilitate this. According this point of view, the accession of many European countries to AIIB is only natural. Arguably, involving European countries in the big new institution while also inviting them to join the New Silk Road project could be aimed at detaching Europe from the United States on the one hand and raising the profile of the yuan in the global economy on the other. It is also actively argued that AIIB is capable of becoming an organization free from corruption and paying substantial attention to environmental issues and social aspects, yet, as our analysis of the AIIB Articles of Agreement has demonstrated, there are no guarantees of that at all.

The need for “internationalization” of the yuan given China’s economic growth and crisis phenomena in the US economy is apparent, and the new institution will facilitate this.

During its first three months in business, the Bank’s operations consisted in the adoption of a number of technical regulations, Jin Liqun’s visits abroad and appointments to secondary positions of representatives from the UK, India and South Korea, a German representative who is also in charge of the World Bank’s International Development Association, and representatives from Indonesia and Pakistan (note that Russia – China’s strategic partner, the third largest contributor to and one of the countries with the biggest expectations of AIIB – received none of the appointments).

Anti-graft policies and environmental standards are just some of the many questions being raised with regard to the new institution. Even the Environmental and Social Framework adopted by the Bank’s management in February 2016 is nothing but a technical regulation, a formal declarative document that has not even been signed by member countries. What projects will AIIB give preference to? How will the vague language of its Articles of Agreement be construed? Isn’t AIIB redundant to the BRICS New Development Bank and the Silk Road Foundation? So far there have been more questions than answers. Yet we would like to hope that with participation of all member countries in its activities, AIIB will be able eventually to outgrow the role of a financial tool of Chinese diplomacy and promote economic cooperation in Asia-Pacific, help improve the living standards in developing nations and attract attention to their developmental issues.

1. Articles of Agreement // The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank official website// Article 1.

2. Ibid. Article 2.

3. Ibid. Article 5, Paragraph 2.

4. Ibid. Article 3, Paragraph 3.

5. Ibid. Article 4, Paragraph 4.

6. Ibid. Article 6, Paragraph 5. Note that in the case of appreciation, it is the Bank that must make an additional payment.

7. Ibid. Article 8.

8. Ibid. Article 11.

9. Ibid. Article 12.

10. Ibid. Article 13, Paragraph 1.

11. Ibid. Article 13, Paragraph 4.

12. Ibid. Article 16, Paragraph 9.

13. Ibid. Article 18.

14. Ibid. Article 24.

15. Ibid. Article 25.

16. Ibid. Article 28, Paragraph 3.

17. Ibid. Article 32.

18. Ibid. Article 34.

19. Ibid. Article 37.

20. With $6,536.2 million, Russia is the third largest contributor after China and India. Articles of Agreement // The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank official website.

21. Ibid. Article 6, Paragraph 4.

(no votes) |

(0 votes) |