North Korea's Cyber

How DPRK Created World's Most Effective Cyber Forces

North Korea's Cyber

How DPRK Created World's Most Effective Cyber Forces

Contents

Introduction

In 2016, when a spelling error stopped North Korean hackers from stealing USD 1 billion from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Internet users made fun of the programmers. However, experts involved in the investigation of cybercrimes are not laughing: as of today, Pyongyang has one of the most effective and dangerous hacker armies in the world, comparable in number to the cyber forces of the United States.

In recent months, the discussions about the upcoming "nuclear truce" between Pyongyang and the rest of the world have intensified against the backdrop of the historic meetings of the leaders of North and South Korea, and Kim Jong-Un's meeting with the U.S. President Donald Trump. However, the "indulgence" of DPRK on this issue may be related to the successes in the digital sector. Today Pyongyang possesses effective cyber weapons, whose damage can be as serious as that of an atomic bomb.

Aleksander Atamanov, PhD in Technical Sciences, CEO and Co-Founder of TSS Ltd (security solutions development company), and Aleksander Mamaev, PhD in Technical Sciences, CEO of Digital Forensic Laboratory (specializing in investigations of cyber incidents), conducted an extensive study on the development of North Korean cyber forces, as well as on the tactics and strategy of North Korean hackers.

In recent months, the discussions about the upcoming "nuclear truce" between Pyongyang and the rest of the world have intensified against the backdrop of the historic meetings of the leaders of North and South Korea, and Kim Jong-Un's meeting with the U.S. President Donald Trump. However, the "indulgence" of DPRK on this issue may be related to the successes in the digital sector. Today Pyongyang possesses effective cyber weapons, whose damage can be as serious as that of an atomic bomb.

Aleksander Atamanov, PhD in Technical Sciences, CEO and Co-Founder of TSS Ltd (security solutions development company), and Aleksander Mamaev, PhD in Technical Sciences, CEO of Digital Forensic Laboratory (specializing in investigations of cyber incidents), conducted an extensive study on the development of North Korean cyber forces, as well as on the tactics and strategy of North Korean hackers.

Key Points

1

DPRK has been actively developing cyber forces since the 2000s. To date the numbers they operate are comparable to the cyber forces of the United States (6–7 thousand people).

North Korean cyber forces are recognized by experts from the U.S. and the EU as one of the most effective and strong cyber armies in the world along, with the U.S., China, Russia, and Israel.

2

The tactics of North Korean cyber forces has undergone three main stages in development: from "ideological" attacks (British Channel 4 and Sony Pictures in 2014) to hacker earnings (diversion of funds from banks and users, crypto fraud), to legal business in software development and sales.

According to experts, cyber activity can earn DPRK up to USD 1 billion a year (for comparison: DPRK GDP in 2016 was estimated USD 28 billion). Devastating attacks on the critical infrastructure of South Korea, the United States, and other countries could be the fourth stage of cyber development.

3

North Korean cyber forces can be divided into four groups, differing in the objectives and methods of attacks:

— Stardust Chollima specializes in "commercial attacks";

— Silent Chollima acts against the media and government agencies, primarily in South Korea;

— Labyrinth Chollima focuses on countering intelligence services;

— Ricochet Chollima is engaged in stealing user data.

— Silent Chollima acts against the media and government agencies, primarily in South Korea;

— Labyrinth Chollima focuses on countering intelligence services;

— Ricochet Chollima is engaged in stealing user data.

4

At the same time, North Korea itself, in comparison with other countries, is more protected from cyber-attacks, because its infrastructure is poorly integrated into the cyber world.

Tracking DPRK's hacker attacks is becoming increasingly difficult because the level of training in North Korea is growing, and the groups themselves are scattered all over the world, from Japan to the countries of the Middle East. "Traditional" methods for identifying the organizers of attack (by IP, servers, or "linguistic traces" within the code) practically do not work.

Сode Testing: Historical Background

"Warfare in the 21st century is about information"

Kim Jong Il

Kim Jong Il

Kim Jong Il, DPRK leader from 1994 to 2011, initially regarded the Internet as a potential threat to his regime. The attitude of the dictator started changing in the mid-1990s, when a group of computer technology specialists returned to the country after graduation. He completely changed his opinion of cyber capabilities, after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. According to the famous North Korean defector Kim Heung-kwang, Kim Jong Il once said: "Warfare in the 21st century is about information".

Pyongyang began actively employing digital technologies for espionage and cyberattacks in the early 2000s. Soon hackers achieved their first success: in 2009, they attacked the U.S. and South Korea websites, infecting them with MyDoom virus. The Lazarus group (also known as Hidden Cobra), currently the most famous hacker group in DPRK, was responsible for the attack.

However, the scale of DPRK cyber usage remained unimpressive when compared to the rest of the world. In 2011, the country was estimated to have about 1,000 IP addresses — less than in most neighborhoods in New York City.

Pyongyang began actively employing digital technologies for espionage and cyberattacks in the early 2000s. Soon hackers achieved their first success: in 2009, they attacked the U.S. and South Korea websites, infecting them with MyDoom virus. The Lazarus group (also known as Hidden Cobra), currently the most famous hacker group in DPRK, was responsible for the attack.

However, the scale of DPRK cyber usage remained unimpressive when compared to the rest of the world. In 2011, the country was estimated to have about 1,000 IP addresses — less than in most neighborhoods in New York City.

Everything has changed under Kim Jong-Un

Everything has changed under Kim Jong-Un. For the first time, the world media was actively reporting on North Korean hackers in 2014. There were two reasons for this: First, in August 2014, cybercriminals attacked the British TV channel Channel 4, after the channel announced they were shooting a film about a British scientist kidnapped by Pyongyang and forced to help develop nuclear weapons. Though the attack did not inflict serious damage, it was just a prelude for what was to come.

In December 2014, Sony stopped the distribution of Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen's "The Interview," a comedy about two journalists dispatched to Pyongyang to assassinate North Korea's young new dictator at the request of the CIA, after repeated terrorist threats. Sony Pictures was subjected to a massive attack when North Korean hackers penetrated deep into Sony's networks, stole several films that were distributed for download on the internet, and released a virus that destroyed up to 70% of laptops and computers of Sony employees. Amid the scandal, Sony Chairperson Amy Pascal resigned, and Sony had to face numerous lawsuits.

After the attack however, hackers gradually shifted from ideological attacks to obtaining illicit earnings on the Web.

In December 2014, Sony stopped the distribution of Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen's "The Interview," a comedy about two journalists dispatched to Pyongyang to assassinate North Korea's young new dictator at the request of the CIA, after repeated terrorist threats. Sony Pictures was subjected to a massive attack when North Korean hackers penetrated deep into Sony's networks, stole several films that were distributed for download on the internet, and released a virus that destroyed up to 70% of laptops and computers of Sony employees. Amid the scandal, Sony Chairperson Amy Pascal resigned, and Sony had to face numerous lawsuits.

After the attack however, hackers gradually shifted from ideological attacks to obtaining illicit earnings on the Web.

USD 1bn a Year

In 2015, groups associated with Pyongyang attacked online banks in the Philippines, and Vietnam (Tien Phong), and in February 2016 — in Bangladesh

In 2015, groups associated with Pyongyang attacked online banks in the Philippines, and Vietnam (Tien Phong), and in February 2016 — in Bangladesh

In 2017, DPRK earned about USD 200 million from banned exports of coal and arms, according to a secret report by independent UN observers. Shipments were carried out through ports in Russia, China, Malaysia, Vietnam, Syria, and Myanmar.

The list of criminal assets and enterprises keeps growing. Over the past 20 years, Pyongyang has repeatedly been accused of counterfeit trafficking (from clothing to cigarettes), distribution of counterfeit currency, and drug trafficking.

Now, Korean officials have discovered a new and far safer way to earn money through hacker attacks. According to Simon Choi, consultant for the National Intelligence Service of South Korea, over the past few years hackers have struck more than 100 banks and cryptocurrency exchanges around the world, pilfering more than USD 650 million. One former British intelligence chief estimates the cyber heists may bring North Korea as much as USD 1 billion a year. For comparison, North Korea's exports amount to just over USD 3 billion, and North Korea's GDP in 2016 was estimated at USD 28.6 billion. "I would not be surprised if hacking now plays a major role in their revenue structure," says Andrei Lankov, leading specialist on North Korea and professor at Kunming University (Seoul).

Hacking is an ideal tool to supplement DPRK's budget for several reasons:

1. Low cost of entering the business: an experienced specialist will just need a computer, access to the Internet, and a server;

2. Anonymity of the user, anonymity of money transactions;

3. Variability of earnings: from legal freelance tasks to illegal targeted attacks;

4. Possibility of evading UN sanctions, including the ban on hiring workers from DPRK.

Let's consider the "commercial attacks" of DPRK in further detail.

The list of criminal assets and enterprises keeps growing. Over the past 20 years, Pyongyang has repeatedly been accused of counterfeit trafficking (from clothing to cigarettes), distribution of counterfeit currency, and drug trafficking.

Now, Korean officials have discovered a new and far safer way to earn money through hacker attacks. According to Simon Choi, consultant for the National Intelligence Service of South Korea, over the past few years hackers have struck more than 100 banks and cryptocurrency exchanges around the world, pilfering more than USD 650 million. One former British intelligence chief estimates the cyber heists may bring North Korea as much as USD 1 billion a year. For comparison, North Korea's exports amount to just over USD 3 billion, and North Korea's GDP in 2016 was estimated at USD 28.6 billion. "I would not be surprised if hacking now plays a major role in their revenue structure," says Andrei Lankov, leading specialist on North Korea and professor at Kunming University (Seoul).

Hacking is an ideal tool to supplement DPRK's budget for several reasons:

1. Low cost of entering the business: an experienced specialist will just need a computer, access to the Internet, and a server;

2. Anonymity of the user, anonymity of money transactions;

3. Variability of earnings: from legal freelance tasks to illegal targeted attacks;

4. Possibility of evading UN sanctions, including the ban on hiring workers from DPRK.

Let's consider the "commercial attacks" of DPRK in further detail.

A Billion Dollar Case: The Central Bank of Bangladesh

In 2015, groups associated with Pyongyang attacked online banks in the Philippines, and Vietnam (Tien Phong), and in February 2016 — in Bangladesh. The attack on the Central Bank of Bangladesh was the most successful and most illustrative of the three. The hackers managed to get access to the accounts of the bank's employees and hack the SWIFT system (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications), which is used by 11 thousand banks and other financial organizations around the world. Hacking SWIFT was necessary in order to later erase information about illegal transfers.

The criminals sent a request on behalf of the Central Bank of Bangladesh to transfer almost USD 1 billion from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, where the funds of the Asian state were kept. The request came on Thursday night, when the Central Bank staff left the office (Friday is a day off in Bangladesh). Only a hacker's typo helped stop the heist: the documents referred to "fandation" instead of "foundation". Big part of the transfer was blocked, but hackers still managed to withdraw USD 81 million and cashed the money through Filipino casinos. This is one of the first cases when cyber-attack was used by the state not for espionage or political purposes, but for profit.

The criminals sent a request on behalf of the Central Bank of Bangladesh to transfer almost USD 1 billion from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, where the funds of the Asian state were kept. The request came on Thursday night, when the Central Bank staff left the office (Friday is a day off in Bangladesh). Only a hacker's typo helped stop the heist: the documents referred to "fandation" instead of "foundation". Big part of the transfer was blocked, but hackers still managed to withdraw USD 81 million and cashed the money through Filipino casinos. This is one of the first cases when cyber-attack was used by the state not for espionage or political purposes, but for profit.

Technical comment

The hackers used evtdiag.exe, a malicious code, that made minor changes to the Access Alliance software code. Fraudsters modified the database where SWIFT network recorded information about the money transfers being made. The malicious software erased outbound requests for funds transfer and intercepted incoming messages confirming the transaction. In addition, the amounts stored on the account were under control in order to prevent detection of the attack, until all funds were transferred to the right accounts. Finally, the software manipulated printers that print hard copies of money transfer requests.

The attack became possible due to the absence of a firewall in the security system of the Central Bank of Bangladesh and the use of cheap switches connected to SWIFT. Another reason for the success of the hacking was the omissions in defense: the room with four servers and four monitors was located in a small separate building of the bank.

The penetration led to a change in information security requirements for all SWIFT participants, that came into force in January 2017.

The attack became possible due to the absence of a firewall in the security system of the Central Bank of Bangladesh and the use of cheap switches connected to SWIFT. Another reason for the success of the hacking was the omissions in defense: the room with four servers and four monitors was located in a small separate building of the bank.

The penetration led to a change in information security requirements for all SWIFT participants, that came into force in January 2017.

WannaCry Hasty Attack

In May 2017, the Internet was paralyzed by WannaCry network worm, that encrypted all files stored on the computer and requiring redemption to unlock. About 300,000 users in 150 countries were affected were affected by the worm in the first four days of the attack. The damage from the attack is estimated at USD 1 billion.

Kaspersky Lab and Symantec antivirus company specialists noticed that WannaCry code is similar to the code used in February 2015 by Lazarus hacker group. The similarity of the code is clear evidence of DPRK involvement in the WannaCry attack.

However, there are questions about whether the attack was intentional. Most likely, the attack was a test of Pyongyang's cyber capabilities. There are several considerations that support this hypothesis.

1. Among the hardest hit countries by the WannaCry virus were China and Russia. The victims included about 30,000 organizations in China: universities, hospitals, traffic police, shopping malls, gas stations, and railroad stations. China and Russia are the main geopolitical and trading partners of DPRK, so it is doubtful that Pyongyang deliberately struck its allies.

2. The attack only resulted in minor financial gain. Having earned only 40 to 70 thousand USD from the attack, it is unlikely that hackers can consider the operation successful, as targeted attacks bring in much more money.

It is possible that WannaCry was only a preparatory stage in the development of a powerful cyber weapon or testing existing developments.

Nevertheless, WannaCry can be classified as a commercial development aimed at both profit-making and surveillance over financial institutions.

Kaspersky Lab and Symantec antivirus company specialists noticed that WannaCry code is similar to the code used in February 2015 by Lazarus hacker group. The similarity of the code is clear evidence of DPRK involvement in the WannaCry attack.

However, there are questions about whether the attack was intentional. Most likely, the attack was a test of Pyongyang's cyber capabilities. There are several considerations that support this hypothesis.

1. Among the hardest hit countries by the WannaCry virus were China and Russia. The victims included about 30,000 organizations in China: universities, hospitals, traffic police, shopping malls, gas stations, and railroad stations. China and Russia are the main geopolitical and trading partners of DPRK, so it is doubtful that Pyongyang deliberately struck its allies.

2. The attack only resulted in minor financial gain. Having earned only 40 to 70 thousand USD from the attack, it is unlikely that hackers can consider the operation successful, as targeted attacks bring in much more money.

It is possible that WannaCry was only a preparatory stage in the development of a powerful cyber weapon or testing existing developments.

Nevertheless, WannaCry can be classified as a commercial development aimed at both profit-making and surveillance over financial institutions.

Technical comment

TSS specialists carefully studied the source code of the malicious program. It turned out that WannaCry is an infecting and at the same time encrypting exploit that is downloaded to the computer after infection.

WannaCry is distributed through file sharing protocols installed on automated workstations. Penetrating into the folder with the documents, the virus encrypted them, changing the extension to .WNCRY, and then required the user to purchase a special key to unlock. Otherwise, hackers threatened to delete all files. The greatest damage was done to computers running a 64-bit version of Windows 7.

WannaCry is distributed through file sharing protocols installed on automated workstations. Penetrating into the folder with the documents, the virus encrypted them, changing the extension to .WNCRY, and then required the user to purchase a special key to unlock. Otherwise, hackers threatened to delete all files. The greatest damage was done to computers running a 64-bit version of Windows 7.

In February 2017, the SIEM system helped to prevent an attack on the Polish financial regulatory authority — the Polish Financial Oversight Commission. Hackers modified one of the JavaScript files and placed a malicious JS script on the resource that loaded malicious software. Once inside the system, the malicious software contacted the servers located abroad and carried out various actions for the purpose of intelligence and data theft.

It is noteworthy that the software acted directly. Hackers prepared a list of Internet addresses of 103 organizations (most of them banks, both Polish and foreign, including credit organizations of Brazil, Chile, Estonia, Mexico, and even the Bank of America) in order to infect the employees of these institutions. If successful, hackers would be able to gain control over financial flows. However, the hackers were mainly interested in information about the market, rather than theft of funds directly.

In March 2018, referring to McAfee, Turkish media reported a hacker group targeting the financial system of Turkey. Based on the code similarity, the victim's business sector, and the presence of control server strings, this attack resembles previous attacks by Hidden Cobra (Lazarus) conducted against the global financial network SWIFT. Phishing emails included Microsoft Word files contained the built-in Adobe Flash exploit. However, in the course of the investigation, analysts found out that the operation in Turkey was only part of a large-scale Operation GhostSecret, affecting a total of 17 countries and aimed at gathering information about critical infrastructure, telecommunications, and even entertainment organizations.

It is assumed that zero-day vulnerabilities in Adobe Flash were found by North Korean hackers and were silenced for a long time. A group of built-in malicious SWF files in the software allowed the hacker to gain complete control over the victim's computers. After Adobe had released a security patch, hackers modified malware to target European financial institutions, allowing them to steal confidential information about the market.

It is noteworthy that the software acted directly. Hackers prepared a list of Internet addresses of 103 organizations (most of them banks, both Polish and foreign, including credit organizations of Brazil, Chile, Estonia, Mexico, and even the Bank of America) in order to infect the employees of these institutions. If successful, hackers would be able to gain control over financial flows. However, the hackers were mainly interested in information about the market, rather than theft of funds directly.

In March 2018, referring to McAfee, Turkish media reported a hacker group targeting the financial system of Turkey. Based on the code similarity, the victim's business sector, and the presence of control server strings, this attack resembles previous attacks by Hidden Cobra (Lazarus) conducted against the global financial network SWIFT. Phishing emails included Microsoft Word files contained the built-in Adobe Flash exploit. However, in the course of the investigation, analysts found out that the operation in Turkey was only part of a large-scale Operation GhostSecret, affecting a total of 17 countries and aimed at gathering information about critical infrastructure, telecommunications, and even entertainment organizations.

It is assumed that zero-day vulnerabilities in Adobe Flash were found by North Korean hackers and were silenced for a long time. A group of built-in malicious SWF files in the software allowed the hacker to gain complete control over the victim's computers. After Adobe had released a security patch, hackers modified malware to target European financial institutions, allowing them to steal confidential information about the market.

The Calm before the Cyber Storm: When the Blackout Appears on the Horizon

"They are extremely aggressive"

Director of the analytical division at FireEye John Hallquist

Director of the analytical division at FireEye John Hallquist

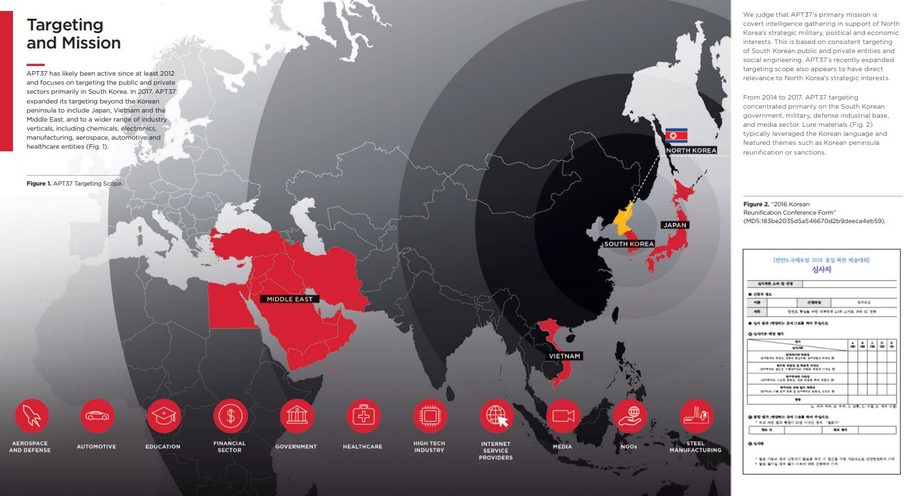

At the beginning of 2018, the analysts from FireEye (among the top 10 of the world's cybersecurity companies, one of the founders of the zero-day threat protection systems) reported on the destructive activities of APT37 group (also known as Reaper), that demonstrated complex high-level hacking opportunities. Director of the analytical division at FireEye John Hallquist said that these hackers "are not shy: they are extremely aggressive." The FireEye report underscored that the main task of APT37 is secret intelligence gathering to support strategic military, political, and economic interests of DPRK.

APT37 activities cover the region from Asia to the Middle East

At the beginning of 2018, the analysts from FireEye (among the top 10 of the world's cybersecurity companies, one of the founders of the zero-day threat protection systems) reported on the destructive activities of APT37 group (also known as Reaper), that demonstrated complex high-level hacking opportunities. Director of the analytical division at FireEye John Hallquist said that these hackers "are not shy: they are extremely aggressive." The FireEye report underscored that the main task of APT37 is secret intelligence gathering to support strategic military, political, and economic interests of DPRK.

Unlike Lazarus, APT37 deliberately works on the sidelines and tries not to get in the spotlight. Its activities cover the region from Asia to the Middle East, and the attacks are becoming more sophisticated. FireEye believes that APT37 was founded in 2012 and is based in North Korea. At the moment, their sphere of interest extends from energy sector, oil industry, and electronics, to the automotive industry and the aerospace industry. The hackers' tactics vary from the destruction of user data to the complete hidden control over the automated working station. Using phishing methods and spreading the malicious DogCall software, the attackers took screenshots of the pages, obtaining passwords of the employees of the South Korean government in March and April 2017. By doing this, hackers managed to steal military documents, including South Korea and the United States joint operational and combat plans for the conflict with Pyongyang. Also, a Middle Eastern telecommunications company and a Vietnamese trading company became victims of the hackers.

The Wall Street Journal states that, over the past 18 months, digital fingerprints of the hackers from North Korea have been traced to an increasing number of cyber attacks. According to the paper, "the skill level of hackers has rapidly improved," and the targets have become more worrisome.

In 2017, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of South Korea reported that over the past 10 years, the number of attempts to access state-owned energy companies Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) increased 4 thousand fold. At least 19 attacks on KEPCO originated in DPRK.

This is a very alarming signal because it indicates that Pyongyang can gain control over the energy sector, and has long been "making a price point" for the industry. Back in 2014, hackers gained access to information from the Chinese nuclear operator KHNP, that cooperates with South Korea. Although South Korean officials claimed that critical data was not stolen, the fact that an attack took place is alarming.

In September 2017, Dragos, a Maryland company specializing in vulnerabilities of the industry sector, indexed the suspicious activity of the Covellite group, that aimed attacks at the energy system in the U.S., Europe, and East Asia. The methods of the attackers were very similar to those of Lazarus. Although the company did not directly link the group to Pyongyang, the U.S. has publicly identified hackers as members of Lazarus.

At the same time, analysts noted that Covellite had not demonstrated "proper professionalism". However, it is difficult to come to any decisive conclusions as it is possible that these actions were an attempt to "indicate intentions" or to "probe" the weak points of the system.

The U.S. power grid is more difficult to hack into than the grid in South Korea. There are many private, independent suppliers in the US, and enterprises often use outdated manual control systems, which complicates the task.

Dragos experts suggested that attackers can develop malware that can lead to a complete shutdown of the U.S. electricity grid. More than half of the vulnerabilities identified in the U.S. industrial sector can potentially lead to a "strong operational impact," as stated in the January Dragos report. The company analyzed 163 new security vulnerabilities that appeared last year in the industrial-grade components control and found that 61% of them are likely to cause "serious operational impact" if targeted in cyberattacks. Most vulnerabilities can only be used if an attacker has access to the enterprise network. However, there is concern over how quickly the equipment manufacturers inform utility services about security holes. Often, manufacturers do nothing, even if the vulnerabilities are already detected and described. Control over the energy grid can become a powerful trump card in Pyongyang's negotiations with Washington.

The DPRK's cyber arsenal is growing as hackers continue developments. In December 2017, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security reported that "destructive malware" SMASHINGCOCONUT can be attributed to the DPRK. According to Eric Chien, an analyst with security firm Symantec, if North Korea was behind the SMASHINGCOCONUT attack, the malware marks a shift for Pyongyang's hackers, who in recent years have focused on attacking financial institutions and bitcoin exchanges.

Unlike Lazarus, APT37 deliberately works on the sidelines and tries not to get in the spotlight. Its activities cover the region from Asia to the Middle East, and the attacks are becoming more sophisticated. FireEye believes that APT37 was founded in 2012 and is based in North Korea. At the moment, their sphere of interest extends from energy sector, oil industry, and electronics, to the automotive industry and the aerospace industry. The hackers' tactics vary from the destruction of user data to the complete hidden control over the automated working station. Using phishing methods and spreading the malicious DogCall software, the attackers took screenshots of the pages, obtaining passwords of the employees of the South Korean government in March and April 2017. By doing this, hackers managed to steal military documents, including South Korea and the United States joint operational and combat plans for the conflict with Pyongyang. Also, a Middle Eastern telecommunications company and a Vietnamese trading company became victims of the hackers.

The Wall Street Journal states that, over the past 18 months, digital fingerprints of the hackers from North Korea have been traced to an increasing number of cyber attacks. According to the paper, "the skill level of hackers has rapidly improved," and the targets have become more worrisome.

In 2017, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of South Korea reported that over the past 10 years, the number of attempts to access state-owned energy companies Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) increased 4 thousand fold. At least 19 attacks on KEPCO originated in DPRK.

This is a very alarming signal because it indicates that Pyongyang can gain control over the energy sector, and has long been "making a price point" for the industry. Back in 2014, hackers gained access to information from the Chinese nuclear operator KHNP, that cooperates with South Korea. Although South Korean officials claimed that critical data was not stolen, the fact that an attack took place is alarming.

In September 2017, Dragos, a Maryland company specializing in vulnerabilities of the industry sector, indexed the suspicious activity of the Covellite group, that aimed attacks at the energy system in the U.S., Europe, and East Asia. The methods of the attackers were very similar to those of Lazarus. Although the company did not directly link the group to Pyongyang, the U.S. has publicly identified hackers as members of Lazarus.

At the same time, analysts noted that Covellite had not demonstrated "proper professionalism". However, it is difficult to come to any decisive conclusions as it is possible that these actions were an attempt to "indicate intentions" or to "probe" the weak points of the system.

The U.S. power grid is more difficult to hack into than the grid in South Korea. There are many private, independent suppliers in the US, and enterprises often use outdated manual control systems, which complicates the task.

Dragos experts suggested that attackers can develop malware that can lead to a complete shutdown of the U.S. electricity grid. More than half of the vulnerabilities identified in the U.S. industrial sector can potentially lead to a "strong operational impact," as stated in the January Dragos report. The company analyzed 163 new security vulnerabilities that appeared last year in the industrial-grade components control and found that 61% of them are likely to cause "serious operational impact" if targeted in cyberattacks. Most vulnerabilities can only be used if an attacker has access to the enterprise network. However, there is concern over how quickly the equipment manufacturers inform utility services about security holes. Often, manufacturers do nothing, even if the vulnerabilities are already detected and described. Control over the energy grid can become a powerful trump card in Pyongyang's negotiations with Washington.

The DPRK's cyber arsenal is growing as hackers continue developments. In December 2017, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security reported that "destructive malware" SMASHINGCOCONUT can be attributed to the DPRK. According to Eric Chien, an analyst with security firm Symantec, if North Korea was behind the SMASHINGCOCONUT attack, the malware marks a shift for Pyongyang's hackers, who in recent years have focused on attacking financial institutions and bitcoin exchanges.

Technical comment

SMASHINGCOCONUT — 32-bit malware based on Microsoft Windows can make a Windows-based system inoperable. After the malware is installed, the hacker inserts the argument in the command line, and the malware deletes all files, and also encode all the data on the computer.

In addition to targeted and scattered cyberattacks, DPRK was interested in the opportunity to track users and collect confidential data. Three apps were available on Google Play for two months (from January to March 2018) that collected information about the device, personal photos, copied contacts and text messages for the DPRK.

The applications were spread to selected defectors from North Korea, who settled in other countries, primarily in South Korea. Though the applications were downloaded only about 100 times, this was exactly the goal. The developers of spyware often infect a small number of carefully selected targets in order to remain unnoticed by the administration of the markets.

Several facts revealed the North Korean origin of applications. McAfee analysts found some of the Korean words on the malware's control server that are not in South Korean vocabulary, which exposed an IP address implicating North Korea. The developers, however, are not linked to the previously identified hackers. The new group was named Sun Team and it is possible that this is one of the units of Lazarus.

Pyongyang is further developing software that can target iPhone users' surveillance systems. In May 2018, cybersecurity researcher Darien Huss from Proofpoint found software — a mobile device management (MDM) tool — that allows hackers to remotely monitor and control employees' phones. The app was located on a server believed to contain other hacking tools linked to one of the bigger North Korean hacking groups. The application allows hackers to fully monitor iPhone users' locations, contacts, and messages.

It is possible that there are even further tools that target the iPhone being developed. Moreover, other countries are engaged in similar developments. For example, Cellebrite, an Israel-based vendor, managed develop a software that unlocks the iPhone. Interestingly, the company is a contractor of the U.S. government.

The applications were spread to selected defectors from North Korea, who settled in other countries, primarily in South Korea. Though the applications were downloaded only about 100 times, this was exactly the goal. The developers of spyware often infect a small number of carefully selected targets in order to remain unnoticed by the administration of the markets.

Several facts revealed the North Korean origin of applications. McAfee analysts found some of the Korean words on the malware's control server that are not in South Korean vocabulary, which exposed an IP address implicating North Korea. The developers, however, are not linked to the previously identified hackers. The new group was named Sun Team and it is possible that this is one of the units of Lazarus.

Pyongyang is further developing software that can target iPhone users' surveillance systems. In May 2018, cybersecurity researcher Darien Huss from Proofpoint found software — a mobile device management (MDM) tool — that allows hackers to remotely monitor and control employees' phones. The app was located on a server believed to contain other hacking tools linked to one of the bigger North Korean hacking groups. The application allows hackers to fully monitor iPhone users' locations, contacts, and messages.

It is possible that there are even further tools that target the iPhone being developed. Moreover, other countries are engaged in similar developments. For example, Cellebrite, an Israel-based vendor, managed develop a software that unlocks the iPhone. Interestingly, the company is a contractor of the U.S. government.

DPRK Is Really Interested in the Cryptocurrency Theme

South Korean projects were the first to be damaged by North Korean hackers

South Korean projects were the first to be damaged by North Korean hackers

The DPRK authorities increased interest in cryptocurrencies deserves special attention. For 9 years since the launch of bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have evolved from hobby into a full-fledged financial instrument. In December 2017, the combined market value of cryptocurrencies surpassed an all-time high of USD 500 billion. At the moment, over 1100 crypto-currencies are circulating on digital exchanges, the number of active users of virtual wallets storing cryptocurrencies grew from 2.9 million in 2013 up to 5.8 million people in 2017.

According to the Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance (CCAF) report, the majority of crypto-currency holders (over 60%) live in North America and Europe, another 20% live in the Asia-Pacific region. Many countries have officially recognized cryptocurrency as a financial instrument or as a means of payment: in 2015 the European Court amounted transactions in bitcoins to payment transactions with currencies, coins, and banknotes, and recommended EU members to exempt these operations from VAT. Japan recognized bitcoin as a real means of payment in March 2016 and China classified cryptocurrencies as a commodity. Furthermore the U.S. Treasury classified bitcoin as a "decentralized virtual currency" bacin in 2013 and Switzerland amounted it to foreign currencies that are eligible for turnover and be accepted as payment within the country.

In October 2017, following the meeting with Anton Siluanov, Minister of Finance of Russia, Andrei Belousov, Assistant, and Elvira Nabiullina, Head of the Central Bank of Russia, Russian President Vladimir Putin gave instructions to legislate, by July 1, 2018, the status of cryptocurrencies, tokens, smart contracts, and blockchain technology; establish the requirements for the miners, including the registration of these entities, as well as determine the procedure for taxation; regulate public attracting of the funds and the crypto currency by placement of the tokens (ICO) along the lines of the initial placement of securities (IPO). So far, however, there has been no progress in drafting the necessary legislation.

However, crypto projects, like companies, are not always protected from cyberthreats. At various times, crypto-exchanges like MtGox, Bitfinex and NEM, the DAO venture fund, the Coincheck trading platform, and NiceHash online market for cryptocurrency became the victims of the hackers.

Crypto wallets don't tend to be more reliable: according to High-Tech Bridge estimates, over 90% of popular crypto wallets on Google Play are subject to vulnerabilities of one sort or another.

According to the Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance (CCAF) report, the majority of crypto-currency holders (over 60%) live in North America and Europe, another 20% live in the Asia-Pacific region. Many countries have officially recognized cryptocurrency as a financial instrument or as a means of payment: in 2015 the European Court amounted transactions in bitcoins to payment transactions with currencies, coins, and banknotes, and recommended EU members to exempt these operations from VAT. Japan recognized bitcoin as a real means of payment in March 2016 and China classified cryptocurrencies as a commodity. Furthermore the U.S. Treasury classified bitcoin as a "decentralized virtual currency" bacin in 2013 and Switzerland amounted it to foreign currencies that are eligible for turnover and be accepted as payment within the country.

In October 2017, following the meeting with Anton Siluanov, Minister of Finance of Russia, Andrei Belousov, Assistant, and Elvira Nabiullina, Head of the Central Bank of Russia, Russian President Vladimir Putin gave instructions to legislate, by July 1, 2018, the status of cryptocurrencies, tokens, smart contracts, and blockchain technology; establish the requirements for the miners, including the registration of these entities, as well as determine the procedure for taxation; regulate public attracting of the funds and the crypto currency by placement of the tokens (ICO) along the lines of the initial placement of securities (IPO). So far, however, there has been no progress in drafting the necessary legislation.

However, crypto projects, like companies, are not always protected from cyberthreats. At various times, crypto-exchanges like MtGox, Bitfinex and NEM, the DAO venture fund, the Coincheck trading platform, and NiceHash online market for cryptocurrency became the victims of the hackers.

Crypto wallets don't tend to be more reliable: according to High-Tech Bridge estimates, over 90% of popular crypto wallets on Google Play are subject to vulnerabilities of one sort or another.

Technical comment

Experts have studied both apps with the number of installations below 100,000 and those being installed more than 500,000 times. As it turned out, 93% of apps with the number of installations below 100,000 contain at least 3 medium-level vulnerabilities, 90% of apps in this category contained at least 2 dangerous problems. It was also found out that 87% of wallets are vulnerable to "man in the middle" (MITM) attacks, which allows interception of information, 66% of apps contain encrypted confidential data (including passwords and API keys), 57% of apps expose user privacy to risk, 80% of apps send unencrypted data by HTTP, 30% apply unreliable or inefficient encryption, 77% of apps use SSLv3 or TLS 1.0, backends (API or web services) 44% of apps are vulnerable to Poodle attacks. 100% of apps do not have protection against reverse engineering.

According to Group-IB estimates, the total damage from targeted hacker attacks against crypto industry in 2017 amounted to more than USD 160 million. The income from hacker attacks against crypto exchanges varies from USD 1.5 to 72 million. At the same time as a result of a successful attack against a bank, earned criminals only USD 1.5 million on average.

It is not surprising that DPRK is really interested in the cryptocurrency theme: in 2013, TSS analysts identified IP addresses related to North Korea on bitcoin forums.

South Korea is one of the locomotives of the crypto industry. Local projects were the first to be damaged by North Korean hackers. For example, in December 2017 the South Korean projectYoubit lost roughly 17% of its digital coin holdings and soon went bankrupt. Then the bitcoin rate reached USD 20,000, in April the fraudsters managed to steal bitcoins equaling USD 36 million. Seoul also suspects Pyongyang of stealing USD 523 million from the Japanese Coincheck exchange.

Private investors also became victims of hackers. In 2017, hackers from DPRK began massively creating fictitious profiles of attractive girls on Facebook who were allegedly interested in bitcoin and working in crypto industry. The NYU Research Center and other institutions were featured in the fake profiles, and the profiles did not arouse suspicion. Hackers got acquainted with male users of crypto exchanges, then sent Microsoft Word files disguised as postcards or invitations, infecting users' software and gaining access to crypts, that's what analysts familiar with the investigation told.

Another way to make profit is to infect workstations with a virus for crypto currency mining. In January 2018, an American company, AlienVault, found a piece of malicious software that installs the app on the victim's computer to extract Monero currency.

It is not surprising that DPRK is really interested in the cryptocurrency theme: in 2013, TSS analysts identified IP addresses related to North Korea on bitcoin forums.

South Korea is one of the locomotives of the crypto industry. Local projects were the first to be damaged by North Korean hackers. For example, in December 2017 the South Korean projectYoubit lost roughly 17% of its digital coin holdings and soon went bankrupt. Then the bitcoin rate reached USD 20,000, in April the fraudsters managed to steal bitcoins equaling USD 36 million. Seoul also suspects Pyongyang of stealing USD 523 million from the Japanese Coincheck exchange.

Private investors also became victims of hackers. In 2017, hackers from DPRK began massively creating fictitious profiles of attractive girls on Facebook who were allegedly interested in bitcoin and working in crypto industry. The NYU Research Center and other institutions were featured in the fake profiles, and the profiles did not arouse suspicion. Hackers got acquainted with male users of crypto exchanges, then sent Microsoft Word files disguised as postcards or invitations, infecting users' software and gaining access to crypts, that's what analysts familiar with the investigation told.

Another way to make profit is to infect workstations with a virus for crypto currency mining. In January 2018, an American company, AlienVault, found a piece of malicious software that installs the app on the victim's computer to extract Monero currency.

Technical comment

In Digital Forensic Laboratory work practice there were at least two registered cases of infecting computer networks with a virus for Monero mining. The analysis of the code of the malicious software allows to state that the attack used exploits identical to the previous attacks attributed to North Korean hackers.

North Korea's interest in Monero is not accidental. Bitcoin remains the most popular crypto currency in the world. One of the key characteristics of the currency, attracting crypto-enthusiasts, is the "anonymity" of transactions, as transactions in bitcoins are presumably impossible to track. Recently, however, the situation has changed. In early 2018, the Bitfury Group blockchain provider introduced a set of Crystal tools that allows law enforcement officers and private experts to track the path of suspicious transactions to the final recipient or point of sale of the crypto currency. The service establishes a link between the alleged attackers and allows authorities to determine the likelihood of the involvement of individual addresses in illegal activities. And this is not the only solution on the market. Though Monero is not as popular as bitcoin, its safety level is now rated higher.

Exporting Software: Legal Business

Backdoors and User Data Collection

The threats of North Korean software

The threats of North Korean software

Having opted for cyber forces development, DPRK made great strides in training qualified IT personnel. In 2015, North Korean teams won the first, second and third prizes out of more than 7,600 participants from all over the world at the CodeChef international competition organized by an Indian IT company. Three of the top 15 coders in the CodeChef network, numbering about 100,000 users, are DPRK representatives.

It is not surprising that Pyongyang began to actively develop IT-businesses, and keeping the DPRK government ties of these businesses as untraceable as possible. According to a report by James Martin at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies, companies associated with the authorities of DPRK create and sell a variety of software around the world. These companies provide services such as development and administration of sites, file encryption software, VPN-builders, and authentication and face recognition systems.

One of the "core" companies is the Global Communications (Glocom) defense company, that created a network of companies throughout Asia. Future TechGroup company, which is affiliated with Global Communications, recently got a prestigious award at the competition in Switzerland for the face recognition software. Future TechGroup also promoted web development projects in American schools, sold face recognition software to law enforcement agencies of Turkey and other countries.

Another Glocom affiliated company — Adnet International — offers biometric data identification methods for customers in China, Japan, Malaysia, India, Pakistan, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, Great Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Canada, Argentina, and Nigeria. VPN technologies developed by North Korean companies were being sold in Malaysia.

Companies manage to hide links with the government by creating intermediary chains in different countries around the world. It turns out that formally, Pyongyang has no relation to these businesses, though orders open both a huge scope for activities to Pyongyang and a Pandora's box for North Korean customers.

First, no one knows if the software is hiding any backdoors — algorithm defects that are deliberately embedded by the developer and allow unauthorized access to data or management of the operating system and the computer as a whole. It is possible that developers from the DPRK intentionally leave bookmarks in software to penetrate into the system at the right moment and get full control over it.

Second, theoretically, Pyongyang can form a colossal database of individuals and organizations. By providing face recognition and fingerprint recognition programs, they create conditions for collecting information about users. These data can later be used to bypass two-factor authentication in online banking or other resources where biometric information is required.

It is not surprising that Pyongyang began to actively develop IT-businesses, and keeping the DPRK government ties of these businesses as untraceable as possible. According to a report by James Martin at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies, companies associated with the authorities of DPRK create and sell a variety of software around the world. These companies provide services such as development and administration of sites, file encryption software, VPN-builders, and authentication and face recognition systems.

One of the "core" companies is the Global Communications (Glocom) defense company, that created a network of companies throughout Asia. Future TechGroup company, which is affiliated with Global Communications, recently got a prestigious award at the competition in Switzerland for the face recognition software. Future TechGroup also promoted web development projects in American schools, sold face recognition software to law enforcement agencies of Turkey and other countries.

Another Glocom affiliated company — Adnet International — offers biometric data identification methods for customers in China, Japan, Malaysia, India, Pakistan, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, Great Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Canada, Argentina, and Nigeria. VPN technologies developed by North Korean companies were being sold in Malaysia.

Companies manage to hide links with the government by creating intermediary chains in different countries around the world. It turns out that formally, Pyongyang has no relation to these businesses, though orders open both a huge scope for activities to Pyongyang and a Pandora's box for North Korean customers.

First, no one knows if the software is hiding any backdoors — algorithm defects that are deliberately embedded by the developer and allow unauthorized access to data or management of the operating system and the computer as a whole. It is possible that developers from the DPRK intentionally leave bookmarks in software to penetrate into the system at the right moment and get full control over it.

Second, theoretically, Pyongyang can form a colossal database of individuals and organizations. By providing face recognition and fingerprint recognition programs, they create conditions for collecting information about users. These data can later be used to bypass two-factor authentication in online banking or other resources where biometric information is required.

Around 6,000 cyber warfare troops

The non-elite hacker had to earn money himself to buy a computer

The non-elite hacker had to earn money himself to buy a computer

Though almost no one in DPRK has broad access to the Internet, Pyongyang has managed to nurture an army of highly skilled hackers from the best students of mathematics, who are becoming the country's unofficial elite.

Prof Kim Heung-Kwang, a computer science professor from DPRK, who fled to South Korea in 2004, said the country had around 6,000 cyber warfare troops who report directly to the Cabinet General Intelligence Bureau. For comparison: the United States Cyber Command, created by Barack Obama in 2009, has about 700 military and civil servants. The U.S. military maintains 6,200 personnel in its cyber units and the United States does recognize the danger of the threat. Vincent Brooks, commander of United States Forces Korea, is sure that North Korean hackers are some "of the best in the world and the most organized." Adam Meyers, vice president of intelligence at CrowdStrike, agrees that the DPRK is "a formidable cyber adversary".

Donghui Park and Jessica L. Beyer noted "The potential for North Korea to destroy critical infrastructure without a nuclear weapon has largely been ignored, yet Pyongyang has enough cyber offensive capability to cause serious damage."

UK Parliament Defense Committee reported that North Korean cyber-attacks are "far more likely" than a nuclear missile attack. Parliamentarians called for increased extra-budgetary investment in ensuring the cybersecurity of the kingdom. At the same time, the British complained about the acute shortage of qualified personnel. Meanwhile, Pyongyang not facing this issue.

WSJ divides DPRK's cyber subunits into three groups, based on the declarations of defectors and South Korean researchers:

"Group A" attacks foreign objects and is linked to the most high-profile DPRK campaigns, such as WannaCry and Sony attacks;

"Group B" focuses on South Korea, military, and infrastructure secrets;

"Group C" performs low-skilled work, such as targeted e-mail attacks.

However, a different classification would be more appropriate. This classification was first used by Crowdstrike experts (the company has customers in 170 countries around the world, and participated in the investigation of attacks on Sony Pictures and the U.S. Democratic Party). Their methodology takes not only the targets into account, but also the methods the groups use. Analysts used the root word in the name Chollima — a mythical horse with wings, revered in DPRK.

The Lazarus group should not be considered as a single organization: it is appropriate to divide it into four units:

Stardust Chollima specializes in "commercial attacks" that generate revenue;

Silent Chollima acts against the media and government agencies;

Labyrinth Chollima focuses on countering intelligence services;

Ricochet Chollima is responsible for stealing confidential user data.

Recently, another group has been noticed on the Net. This group, the APT37, is apparently not connected with Lazarus, and is trying to stay out of sight and to not attract attention. APT37 is involved in serious penetrations into the systems of various countries from South Korea to the countries of the Middle East.

According to defectors and South Korean experts in the area of cyber intelligence, promising candidates are being selected from the age of 11 and sent to special schools where they teach the basics of cybersecurity and the development of computer programs. The cyber soldiers are given appropriate indulgences: they do not need to worry about accommodation, they get luxury food that other North Koreans do not get, and they can bring their entire family to Pyongyang. Cyber soldiers are also exempted from compulsory military service — they perform a different service.

However, there is a downside: elite cyber-soldiers have elite status. But, like in every army, there is "infantry" in a completely different situation. Bloomberg interviewed North Korean Jong Hyok, who worked in DPRK cyber forces, and produced a lengthy report on the status of the North Korean cyber capabilities. Though the Bloomberg report contains a huge amount of data, it is not possible to verify the validity of all the statements made in it.

The hacker interviewed by Bloomberg did not participate in high-profile operations and was engaged exclusively in making money through illicit online activities. Jong was allocated to Computer Science School, studied in China, and upon returning to his homeland, joined cyber forces, and was sent to the PRC for work. The hacker had to earn money himself to buy a computer. In the beginning he used his hostel roommates' laptop, but later earned his first profit by selling software. Then, he started to hack software on request and in his free time he ravaged gambling sites and developed characters in online games for further resale.

The hackers who did not earn the required rate of USD 100,000 a year were sent back to DPRK. Programmers were allowed to retain less than 10% of the profits.

After the incident with a civil servant, Jong Hyok fled to Bangkok, bought a fake passport and asked the Embassy of South Korea for help, which allowed him to start a new life in Seoul.

In addition to hacking, cyber forces are also engaged in other tasks. On request, hackers develop iOS and Android software, and profits from software sales go to the DPRK treasury. "Branches" of North Korean units are scattered around the world, but most hackers live in China. Given the volume of traffic and careful monitoring of Internet users' requests, the Chinese authorities are certainly aware of the activities of the North Koreans, but no proven measures have been taken against cyber-frauds. Apparently, DPRK and PRC adhere to a silent convention on network non-aggression.

Prof Kim Heung-Kwang, a computer science professor from DPRK, who fled to South Korea in 2004, said the country had around 6,000 cyber warfare troops who report directly to the Cabinet General Intelligence Bureau. For comparison: the United States Cyber Command, created by Barack Obama in 2009, has about 700 military and civil servants. The U.S. military maintains 6,200 personnel in its cyber units and the United States does recognize the danger of the threat. Vincent Brooks, commander of United States Forces Korea, is sure that North Korean hackers are some "of the best in the world and the most organized." Adam Meyers, vice president of intelligence at CrowdStrike, agrees that the DPRK is "a formidable cyber adversary".

Donghui Park and Jessica L. Beyer noted "The potential for North Korea to destroy critical infrastructure without a nuclear weapon has largely been ignored, yet Pyongyang has enough cyber offensive capability to cause serious damage."

UK Parliament Defense Committee reported that North Korean cyber-attacks are "far more likely" than a nuclear missile attack. Parliamentarians called for increased extra-budgetary investment in ensuring the cybersecurity of the kingdom. At the same time, the British complained about the acute shortage of qualified personnel. Meanwhile, Pyongyang not facing this issue.

WSJ divides DPRK's cyber subunits into three groups, based on the declarations of defectors and South Korean researchers:

"Group A" attacks foreign objects and is linked to the most high-profile DPRK campaigns, such as WannaCry and Sony attacks;

"Group B" focuses on South Korea, military, and infrastructure secrets;

"Group C" performs low-skilled work, such as targeted e-mail attacks.

However, a different classification would be more appropriate. This classification was first used by Crowdstrike experts (the company has customers in 170 countries around the world, and participated in the investigation of attacks on Sony Pictures and the U.S. Democratic Party). Their methodology takes not only the targets into account, but also the methods the groups use. Analysts used the root word in the name Chollima — a mythical horse with wings, revered in DPRK.

The Lazarus group should not be considered as a single organization: it is appropriate to divide it into four units:

Stardust Chollima specializes in "commercial attacks" that generate revenue;

Silent Chollima acts against the media and government agencies;

Labyrinth Chollima focuses on countering intelligence services;

Ricochet Chollima is responsible for stealing confidential user data.

Recently, another group has been noticed on the Net. This group, the APT37, is apparently not connected with Lazarus, and is trying to stay out of sight and to not attract attention. APT37 is involved in serious penetrations into the systems of various countries from South Korea to the countries of the Middle East.

According to defectors and South Korean experts in the area of cyber intelligence, promising candidates are being selected from the age of 11 and sent to special schools where they teach the basics of cybersecurity and the development of computer programs. The cyber soldiers are given appropriate indulgences: they do not need to worry about accommodation, they get luxury food that other North Koreans do not get, and they can bring their entire family to Pyongyang. Cyber soldiers are also exempted from compulsory military service — they perform a different service.

However, there is a downside: elite cyber-soldiers have elite status. But, like in every army, there is "infantry" in a completely different situation. Bloomberg interviewed North Korean Jong Hyok, who worked in DPRK cyber forces, and produced a lengthy report on the status of the North Korean cyber capabilities. Though the Bloomberg report contains a huge amount of data, it is not possible to verify the validity of all the statements made in it.

The hacker interviewed by Bloomberg did not participate in high-profile operations and was engaged exclusively in making money through illicit online activities. Jong was allocated to Computer Science School, studied in China, and upon returning to his homeland, joined cyber forces, and was sent to the PRC for work. The hacker had to earn money himself to buy a computer. In the beginning he used his hostel roommates' laptop, but later earned his first profit by selling software. Then, he started to hack software on request and in his free time he ravaged gambling sites and developed characters in online games for further resale.

The hackers who did not earn the required rate of USD 100,000 a year were sent back to DPRK. Programmers were allowed to retain less than 10% of the profits.

After the incident with a civil servant, Jong Hyok fled to Bangkok, bought a fake passport and asked the Embassy of South Korea for help, which allowed him to start a new life in Seoul.

In addition to hacking, cyber forces are also engaged in other tasks. On request, hackers develop iOS and Android software, and profits from software sales go to the DPRK treasury. "Branches" of North Korean units are scattered around the world, but most hackers live in China. Given the volume of traffic and careful monitoring of Internet users' requests, the Chinese authorities are certainly aware of the activities of the North Koreans, but no proven measures have been taken against cyber-frauds. Apparently, DPRK and PRC adhere to a silent convention on network non-aggression.

Cyberattacks of North Korean hackers and nuclear tests have a fairly clear correlation: they often coincide in time. During the third round of nuclear testing in February 2013, South Korean television companies and the banking sector were affected by the cyber attack of 3.20 Cyber Terror, known as DarkSeoul. In January 2016, when North Korea conducted the fourth nuclear explosion, South Korean officials faced mass mailing of phishing letters. After the fifth nuclear test in September 2016, hackers managed to steal secret military files from South Korea. It is possible that Pyongyang diverts attention from cyber-attacks by nuclear tests. World mass media simply has no time to report cyber-attacks when they are focused on covering an atomic explosion.

Cases of attacks against the power grid of South Korea and the United States indicate that DPRK could have begun preparations for the fourth stage of its own cyber strategy. Subsequent strikes can be directed to critical infrastructure, and it is not yet possible to predict the consequences.

Paradoxically, because North Korea's isolation complicates the development of an effective strategy against Pyongyang's cyber-attacks, Washington has to rely on open sources of information. In addition, the attempts to strike back in cyberspace are certainly doomed to failure simply because the country has virtually no access to the Web.

Nevertheless, the U.S. intensified the efforts in cyber arena. In the past year, the US has been covertly laying the groundwork for cyber-attacks that would be routed through South Korea and Japan, where the US has extensive military facilities. The preparations include installing fiber cables in the region and setting up remote bases and listening posts from where hackers will attempt to gain access to North Korea's version of the Internet.

But even if North Korea completely restricts access to the Internet, the attacks will not stop. The North Korean hackers dispersed throughout the world and can continue the attacks from anywhere in Southeast Asia with Internet access. At the same time, Pyongyang cannot be punished for cybercrimes because the most painful sanctions against the country have already been imposed, and no state will be able to conduct a military strike in retaliation for cyberattacks.

Cases of attacks against the power grid of South Korea and the United States indicate that DPRK could have begun preparations for the fourth stage of its own cyber strategy. Subsequent strikes can be directed to critical infrastructure, and it is not yet possible to predict the consequences.

Paradoxically, because North Korea's isolation complicates the development of an effective strategy against Pyongyang's cyber-attacks, Washington has to rely on open sources of information. In addition, the attempts to strike back in cyberspace are certainly doomed to failure simply because the country has virtually no access to the Web.

Nevertheless, the U.S. intensified the efforts in cyber arena. In the past year, the US has been covertly laying the groundwork for cyber-attacks that would be routed through South Korea and Japan, where the US has extensive military facilities. The preparations include installing fiber cables in the region and setting up remote bases and listening posts from where hackers will attempt to gain access to North Korea's version of the Internet.

But even if North Korea completely restricts access to the Internet, the attacks will not stop. The North Korean hackers dispersed throughout the world and can continue the attacks from anywhere in Southeast Asia with Internet access. At the same time, Pyongyang cannot be punished for cybercrimes because the most painful sanctions against the country have already been imposed, and no state will be able to conduct a military strike in retaliation for cyberattacks.

Aleksander Atamanov

PhD in Technical Sciences, CEO and Co-Founder of TSS Ltd, Russian security solutions development company

Together with the development team, he created a unique market-leading high-speed encryption technology using the GOST standard algorithm. Graduate of Moscow Engineering Physics Institute, specializing in Comprehensive Information Security for Automated Systems.

Aleksander Mamaev

PhD in Technical Sciences, CEO of Digital Forensic Laboratory.

For 3 years headed Cryptology and Discrete Mathematics department of NRNU MEPhI. Head of NRNU MEPhI and the University of Surrey (Great Britain) joint project. Participant of GVA LaunchGurus - Startup Academy 5 business accelerator. Took start-up training in the Silicon Valley.

Photos by phonandroid.com, Reuters, EPA, AFP, KCNA, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, The Express Tribune, twitter.com/hack4lifemx

Editing & Production: Maria Smekalova, Maria Gershuni, Irina Sorokina, Alexander Teslya.

© 2018 Russian International Affairs Council

© 2018 Russian International Affairs Council